(Dreamstime/Sergei Chaiko)

Editor's note: This story was updated on May 14, 2020 at 2:15 p.m. to include additional comments from the Alliance of Health Care Sharing Ministries.

Corlyn and Bruce Duncan were looking to renew their health insurance in November 2017, when their broker introduced them to Aliera — a Christian health care sharing ministry that offered plans much cheaper than market price. "Our broker told us it was a new product and it was going to save us money. So we signed up for the gold plan," Bruce told NCR.

A year later, Corlyn was diagnosed with a cyst on her spine and doctors advised surgery. The couple got preapproved by Aliera, but the company later denied payment. The Duncans now owe $125,000 in unpaid medical bills.

Burdened under crushing debt brought on by the coronavirus economy, the couple filed a lawsuit in California on April 29 against Aliera and the nonprofit entity it administers, Trinity HealthShare.

Bruce and Corlyn Duncan (Provided photo)

The Duncans join scores of Americans who have brought similar lawsuits against health care sharing ministries for fraudulent practices. Christian health care sharing ministries, according to critics, offer members inexpensive medical plans under the guise of insurance, deny preexisting conditions, and are under no obligation to pay medical claims.

Recent lawsuits bring to the surface a complex web of religion, money and health care, unfolding at a time when the country is undergoing a serious public health crisis.

Christian health care sharing ministries have become a growing part of America's insurance landscape. They are not insurance. Members pool money to pay for medical care as and when needs arise. It's akin to crowdfunding medical costs. Participants pay a monthly fee, and it's open to those who share common ethical or religious beliefs. The main requirement is that members adhere to a Christian lifestyle.

Many Americans struggling with the high cost of medical insurance are drawn to health care sharing ministries for their attractive pricing. The popular Samaritan Ministries offers a monthly base cost (premium) of $614 for a family of three to seven persons. The Duncans, currently enrolled with Kaiser insurance, are paying $2,600 a month, whereas with Aliera, they paid $1287.56, Bruce told NCR.

However, plans offered by sharing ministries are exempt from the requirements established by the Affordable Care Act. As a result, they provide fewer guarantees.

Unlike traditional insurance, they have no obligation to reimburse members or pay for their treatment. They also have an annual lifetime benefit limit, and if bills exceed the cap, there's no assurance of payment.

"What makes these companies succeed is the illusion of affordability. But what they offer is not going to save people forever. Those who have chronic illness, they won't cover it. They won't cover ongoing care for diabetes, they won't cover ongoing prescription medication," explained Mikael Broadway, professor of theology and ethics at Shaw University Divinity School in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Growth of health cost sharing ministries

Health cost sharing ministries date back at least a century. For decades, the Amish and Mennonite communities pooled money to lighten the burden of medical expenses of those living in their communities who fell on hard times.

In the early 1990s, larger ministries developed from Christian groups that offered similar services. "They began to create systems to support one another's health care, to make sure their fellow church members didn't go bankrupt paying their bills," said Broadway.

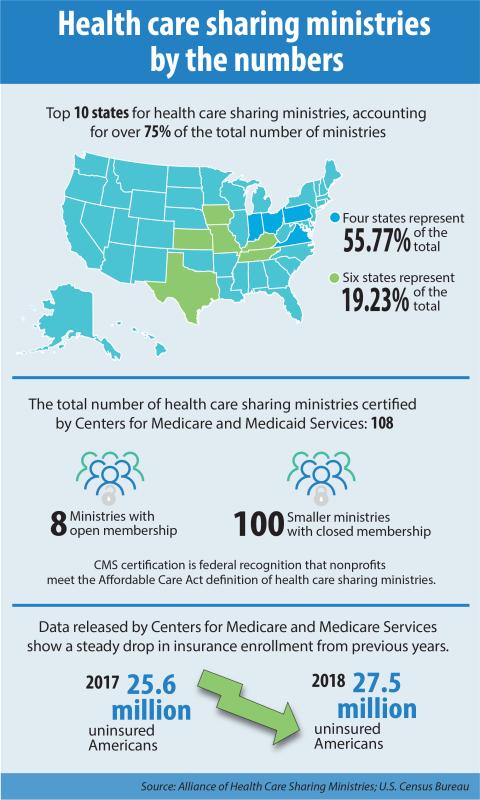

The Alliance of Health Care Sharing Ministries, a trade organization, reports 108 active and known health care sharing ministries (HCSM) certified by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the U.S. While most are small ministries with closed membership, there are some that are large and have open membership.

The trade organization argues that a company such as Aliera should not even be referred to as an HCSM, an industry shorthand for health care sharing ministries, because it lacks the certifications letter from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Some of the big players in the industry are Samaritan Ministries, Liberty HealthShare, Altrua HealthShare, OneShare Health and Zion Health, among others.

Over the years, enrollment in health cost sharing ministries has seen a steady rise, with many Americans ditching traditional health insurance.

Between Nov. 1 and Dec. 21, 2019, approximately 8.3 million Americans signed up for health insurance through the individual marketplace on HealthCare.gov for the 2020 enrollment period. Data released by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services show a steady drop in insurance enrollment from previous years. In 2018, 27.5 million Americans were uninsured, up from 25.6 million in 2017.

Meanwhile, health sharing ministries reported an uptick in membership, according to data from the Alliance of Health Care Sharing Ministries.

The Affordable Care Act created an exemption for health care sharing ministries in 2014. When the act went into effect, an estimated 160,000 people enrolled in the health care sharing programs nationwide, reported PBS. Today, there are around a million members, said Katy Talento, executive director of the Alliance.

"When the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2019 rolled back individual mandate, which fined Americans for choosing health care options outside the ACA exchange, we saw an uptick in members joining HCSMs. Three of the largest ministries saw an average growth in membership of over a 30% from 2017 to 2020," said Talento.

The implementation of the ACA also brought about a larger exodus of more conservative Christians from traditional plans. They saw the insurance market intruding on their beliefs on issues like abortion and found an alternative in health sharing ministries. These ministries often don't cover contraception, abortion or fertility treatments.

"In the ACA, you'd have to share in abortion, contraception and sterilization. But in a health sharing ministry, members decide what we can share," explained Bradley Hahn, CEO of Solidarity HealthShare, a Catholic health cost sharing ministry. "Our members will never have to share in medical expenses that violate the teachings of the church, and that's the driving impetus for our members to join."

Christian nonprofit groups have been successful in promoting this ministry as an alternative to expensive health insurance, and have managed to overlay that with religious and theological appeal. Those wishing to enroll in a health sharing ministry often sign a statement of faith.

"It's a natural consequence of the mix between the notion of a Catholic social teaching's right to health care and religious freedom," said John Carney, president and CEO of the Center for Practical Bioethics, based in Kansas City, Missouri.

Growing troubles

Sharing ministries rely heavily on aggressive marketing — often employing call centers and brokers to sell their products to individuals. Companies like Aliera even sell membership tiers, similar to ACA-compliant insurance products, using terms like gold, silver and bronze to describe their plans.

"They use determinant terminology and the lexicon of health insurance plans. It is clearly designed to fool people into thinking that they are getting comprehensive health care coverage when they're simply not. And that's why state regulators are coming down on them," said Rick Spoonemore, an attorney who has filed class action lawsuits against Aliera and Trinity in Washington, Missouri, California and Colorado.

Trinity HealthShare describes itself as a Christian health care sharing ministry. According to the lawsuit filed by the Duncans, Aliera created Trinity as a nonprofit in June 2018. Aliera controls Trinity's finances and administers its plans, benefits and membership roster.

Trinity is not a "recognized" health care sharing ministry, because it has not been in existence continuously since Dec. 31, 1999, a requirement for such ministries under the Affordable Care Act. Talento confirmed the same, saying Aliera and Trinity "don’t meet the legal or ethical requirements of health care sharing ministries."

In January this year, Washington state told Trinity HealthShare to permanently stop operations in the state and fined the company $150,000 for operating as an unauthorized insurer.

"Many consumers here and in other parts of the country thought they were buying a health insurance plan, only to find out that pre-existing and chronic conditions weren't covered," Washington Insurance Commissioner Mike Kreidler said in a statement.

'What makes these companies succeed is the illusion of affordability. But what they offer is not going to save people forever.'

—Mikael Broadway

Nevada residents were warned against health cost sharing ministries by the Nevada Division of Insurance in a December 2019 release. The state asked consumers to be careful as "they may seem enticing because they may be cheap, look and sound like they are in compliance with the Affordable Care Act ... when in reality these plans are not even insurance products."

The Connecticut Insurance Department issued a cease and desist order against Aliera and Trinity for conducting business in an "illegal and improper way" in December 2019. The two were also issued a cease and desist notice by the New Hampshire Insurance Department, for misleading consumers by "offering, marketing and administering health coverage that does not meet state and federal requirements."

Insurance regulators in New York are investigating Aliera and have issued subpoenas, reported The New York Times. And in Colorado and California, authorities have issued cease and desist orders against Aliera and Trinity, said a Houston Chronicle report.

On April 20, the Insurance Journal reported a class action lawsuit was filed in Missouri against Aliera Companies and Trinity HealthShare for selling "inherently unfair and deceptive health plans" to residents of that state.

Although health cost sharing ministries advertise to everyone, they are notoriously picky in giving out membership.

People seeking low cost health care can be rejected if their behavior is deemed unhealthy or immoral — like smoking, alcohol use, drug use, pregnancy out of wedlock, or risky behaviors like extreme adventure sports.

"There is a kind of puritanism attached to many of these programs. I read about one where they would not cover maternity if the child is born out of wedlock," said Broadway. "These are some of the things they do to limit their population and are not compassionate towards the poor, which is supposed to be their motivation as a Christian organization."

Another concern with health share ministries is that they often refuse to accept people with preexisting conditions. Patients with asthma, heart condition, diabetes and cancer are often left out.

Carney said that many ministries do mention in their documents that they don't cover preexisting conditions, or conditions related to it.

Advertisement

"There's a safety valve for them to say outright they don't cover preexisting conditions. They do claim to provide support through prayer. There's no way one can file an appeal with these groups. This is not an insurance industry product. However, it's their duty to make clear what they're offering," he said.

Last summer, the Texas attorney general's office filed a lawsuit against Aliera, barring it from signing up new members and offering "unregulated insurance products to the public."

According to authorities in the Texas Department of Insurance, only 28 cents of every dollar collected went toward members' medical bills. The larger chunk of 70% went toward "administrative costs."

Said Spoonemore, "They flip the model on its head to the detriment of the individuals. And they're able to sell these products because they put a bunch of money on the brokers to push them."

Catholics and health share

Usually a more evangelical phenomenon, over the past few years groups of Catholic traditionalists have also entered the market to offer health cost sharing programs.

Scholars say that the concept of health sharing is Catholic in its roots.

"This is something the Catholic Church invented," said John Di Camillo, ethicist at the National Catholic Bioethics Center in Philadelphia.

He compared the programs to insurance products sold by the Knights of Columbus. The Knights of Columbus program grew out of deep-rooted Catholic social and moral teaching, trying to serve the needs of immigrant communities in the United States at a time when the working class was dying in harsh labor environments, and their families left with no one to sustain them.

"So again, they're the early roots of creating a system of financial support," said Di Camillo.

Dan Plato, a Catholic living in Cleveland, joined Liberty HealthShare, a non-Catholic health sharing ministry, after becoming self-employed in 2018. Under the Affordable Care Act, the monthly premium for a family of five was around $1,300.

"What attracted me most to health cost sharing, apart from the affordability, was the concept. I'm a liberal Catholic and I wasn't drawn to the religious aspect of it. It was the fellowship idea that sounded wholesome — taking care of your fellow man or woman in time of medical need," said Plato, who blogged extensively about his experience.

A banner is displayed at a 2017 CMF Curo event. (CMF Curo/Courtesy of BringingHeart/Kathy Dempsey)

The two major Catholic players in the market are Solidarity HealthShare and CMF Curo. They describe their mission as deeply rooted in Catholic tradition.

CMF Curo is part of the Christ Medicus Foundation, a nonprofit that reported a revenue of $1,343,304 in 2018, according to tax documents. CMF is financially integrated with Samaritan Ministries International, which has evangelical roots and a total revenue of $39,367,893, as of 2017.

Cardinal Raymond Burke, former archbishop of St. Louis and prefect emeritus of the Apostolic Signatura, has endorsed CMF Curo. Burke has been a strong critic of the ACA, objecting to its requirements that insurance plans offer contraception.

He praised the ministry for offering a Catholic solution to health care. "It is viable because it relies upon a direct patient-physician relationship, because it respects freedom of religion, because it acknowledges that each of us is duty-bound before God to take care of ourselves," reads his statement on the CMF Curo website.

Ethicists say that the danger for Catholic groups is that they could rule out certain kinds of coverage in a way that would not adequately acknowledge the important role of mercy and compassion, especially toward those who are vulnerable.

"There can be a danger that it would tend to skew towards those who are the healthiest patients and sort of penalize people who are not in good physical healthy condition," said ethicist Di Camillo.

There are also risks of financial exploitation by those running the ministry. "When there aren't the same oversight mechanisms that might be in place for the regulated insurance industry, there are chances that people could take advantage of members and misuse the money. Catholic ministries need to be vigilant and transparent," said Di Camillo.

Hahn, the CEO of Solidarity, wishes the Catholic Church had a financial accountability standard for nonprofits to follow. "There's an organization for the Protestant and evangelical churches [Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability]. We are currently following their guidelines. It would be nice if we had one, too," he said.

Transparency and responsibility

Ethicists say that the biggest concerns with health cost sharing ministries are related to issues of transparency and responsibility.

Most health sharing groups are considered to be "churches" for tax purposes and are not required to publicly report their financials, said Carney. "They need to make clear to as sponsors what they give in exchange for the shared portion they're contributing. Also, who owns the money and where does it go? These are important questions," he said.

Health care workers move a patient at NYU Langone Hospital in New York City May 3, amid the coronavirus pandemic. (CNS/Reuters/Eduardo Munoz)

The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted the intertwined nature of community health. "The theological consideration here is — does everyone's health matter?" asked Broadway, professor of ethics and theology. "Caring for those on the margins of society is crucial for Christian ethics."

Carney said people looking for protection against COVID-19-related hospitalization should not be looking toward health sharing ministries. "That's not insurance. So if anyone is looking at this for a way to protect them in a pandemic, it's wrong. I'm never going to suggest that," he said.

The Duncans, meanwhile, are not sure if they have to give up their home and car in a bid to rebuild their lives. As a contractor, Bruce has not had steady income since the lockdown.

"It looks more and more dismal. Amidst all this, we didn't need to have to deal with medical bills and health insurance," he said.

He has a word of caution for people planning on enrolling in health share ministries: "Get online, get diligent, because what your broker tells you is probably not accurate or to your benefit."

[Sarah Salvadore is NCR's Bertelsen editorial intern. Her email address is ssalvadore@ncronline.org.]