A portion of Serpent Mound along Ohio Brush Creek near Peebles, Ohio. (RNS/Stephanie A. Terry/Wikipedia/Creative Commons)

Chief Glenna Wallace spent the summer solstice this past June walking the narrow asphalt path that encircles Serpent Mound, a low, serpentine wall of earth built by her ancestors hundreds or even thousands of years ago.

Wallace, who leads the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, was joined by Chief Ben Barnes of the Shawnee Tribe, and the two talked to crowds of visitors to the historic site about their tribes’ connections to the mound and the 19th-century policies that forced them out of the area.

"We presented programs to let people know that the tribes still exist, the people still exist," Wallace told Religion News Service in a recent phone call. "We are still alive, we are still active. Those are still spiritual places for us."

As they spoke, the sounds of flute music and a "Native American style" drum demonstration filtered through the air from the nearby Soaring Eagle Retreat, where people had gathered to commemorate the solstice with crystal workshops and a presentation by a local Bigfoot investigator and other speakers who suggested that aliens or giants had built the mound.

Southern Ohio is home to more than 70 earthworks constructed by the Indigenous Adena and Hopewell cultures. These structures are still important to their descendants — the Shawnee, Eastern Shawnee, Miami and Delaware people who were pushed out of the area 200 years ago by white American settlers. Some of the structures were built as burial mounds, while others functioned as astronomical observatories or ritual or religious structures.

But the mounds have also taken on significance for other spiritual groups. Terri Rivera, who has been bringing people to celebrate equinoxes and solstices at Serpent Mound for a decade, believes the site should be open to anyone who sees it as a sacred place.

"To me, it's a real healing spot," Rivera said on a visit to the mound in November. "I think people were probably drawn here because of the energy fields."

Theories about the mounds' origins have also led to attacks from fringe evangelical Christians who see them as unholy. Tribal leaders have responded by educating locals about the mounds and working with groups such as Ohio History Connection, the nonprofit that manages Serpent Mound and other mounds throughout Ohio, to ensure they are respected.

"We believe that some of the activities that have occurred there in the past are in direct violation of our beliefs," Wallace said. "And so we're asking that our practices not be violated."

Their efforts are part of a larger battle for access to sacred sites, from mountains in Arizona to rivers in North Dakota, aimed at fending off developers or government agencies to preserve the physical integrity directly linked to their spiritual value.

The federal government is sometimes a partner, and sometimes not. In Ohio, the United States is working to have nine Ohio earthworks, including Serpent Mound, added to the UNESCO's World Heritage list, a move that would provide added resources to safeguard the mounds.

Interest from practitioners of alternative faiths is also a mixed blessing. While New Agers often share a belief in Native American sites' spiritual power, they have sometimes caused damage. In 2012, a group called Unite the Collective, whose members identified themselves as "Light Warriors," buried hundreds of orgonites — balls of crystals and resin, often made in muffin tins — at Serpent Mound in an attempt to focus the earth's vibrations.

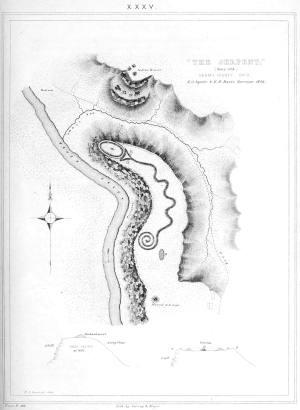

A map of Serpent Mound from "Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley," published by the Smithsonian Institution Press in 1848. (RNS/Wikipedia/Creative Commons)

Sites like Serpent Mound have served as gathering places for New Age spiritual practitioners since the 1987 Harmonic Convergence, when believers congregated on a day they believed was auspicious according to the Mayan calendar. The Newark Earthworks, about 40 minutes east of Columbus, have also drawn attention for supposedly being built along ley lines — invisible gridlines that channel "earth energies."

In 2011, Serpent Mound was featured on an episode of the History Channel's show "Ancient Aliens," in which several people claimed the mound may have been used as a landing site by aliens. (Rivera's husband, Tom Johnson, appeared as a guest on the show, saying he'd heard such stories.)

And the day before the winter solstice last December, Dave Daubenmire, a conservative activist and leader of Pass the Salt Ministries in Hebron, Ohio, led a group to Serpent Mound to perform a prayer to cast out demons from the site. Daubenmire said in a Facebook video that he believed Ohio's earthworks were built by Nephilim, a race of giants some say are the offspring of fallen angels and human women.

For many, these claims echo the racist "Moundbuilder myth," which credits the mounds' construction to an ancient white race — an idea used by 19th-century politicians to justify the expulsion of Native tribes from their lands.

Advertisement

Daubenmire's group was met by protesters from the American Indian Movement of Ohio, though the organization is not sanctioned by the official American Indian Movement. (The group's director, Philip Yenyo, presents himself as Native American but is of Hungarian and Spanish Mexican descent, according to AIM.)

Rivera criticized both Unite the Collective and Pass the Salt Ministries, maintaining that the mounds provide an opportunity for people with different beliefs to come together, provided they respect the site.

"One of our sayings for our events is: all nations, all races, all relationships," said Rivera, who describes herself as having Native American ancestry but is not a member of a recognized tribe. "So it's time to just quit dividing. Just say, hey, let's just all be friends."

But Wallace said that belief in the mounds' spiritual power can lead people to disrespect the mounds' history and sacredness. She has seen people using drugs at Serpent Mound on the winter solstice and heard of people having sex there, believing it would boost their fertility. Even the drumming that took place at the last solstice event, though characterized by organizers as "ceremonial," seemed disrespectful to Wallace — more like a "rock concert" than an act of reverence.

Joe Laycock, an assistant professor of religious studies at Texas State University, said interest in Native American traditions goes back to the Spiritualist movement of the 1800s, when settlers' guilt over the displacement and destruction of Indigenous communities may have driven them to obsession. It boomed in the 1960s, as alternative spiritual practitioners began integrating "pseudo-Native" folklore.

The New Age movement’s syncretism — what Laycock calls a "cultic milieu" of different spiritual beliefs and practices — is evident in the gathering Rivera was organizing in December. The event planned to feature a Peruvian healing ceremony, a presentation by a psychic medium and "animal communicator," ceremonial drumming, lessons in "sacred geology" and traditional Māori dance, or haka.

Not everyone who attends these gatherings identifies as New Age — including Rivera, who said she's broadly spiritual — but this kind of big-tent approach is a hallmark of the movement, Laycock said.

This year, after input from Wallace and Barnes, OHC began restricting groups from gathering directly at the mound, meaning Rivera's Serpent Mound Star Knowledge Winter Solstice Peace Summit will take place six miles away from Serpent Mound.

No matter their beliefs, visitors to the mounds need to show respect for the sites' spiritual nature, said John Low, director of the Newark Earthworks Center and an enrolled citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians. The mounds are no less sacred than a church or a mosque, Low said, though their sacredness is not bound by what is built on the land.

"The earth which they are built upon was sacred, is sacred, will always be sacred," Low said.

This article was produced as part of the RNS/IFYC Religious Journalism Fellowship Program.