BY JOHN L. ALLEN JR.

New York

Back in 1997, the Vatican put out a document on lay ministry, cataloguing a whole index of things laity were not supposed to do. Among other things, it seemed to imply that laity could not act as chaplains, could not be trained in seminaries, and could not have official roles in the liturgy.

Several of these points contradicted existing practice in many American dioceses, and some American bishops were concerned. One bishop, who was in Rome at the time for the Synod for America, later told me how he restored his peace of mind.

“I went up to Cardinal [Camillo] Ruini,” he said, referring to the powerful president of the Italian bishops’ conference. “I asked him what he made of it. His response was, ‘Ah, the pope has a problem in Switzerland,” the bishop recounted.

The impression left by Ruini, at least with this prelate, was that the document was to some extent a response to a specific local situation, and not meant to be applied slavishly everywhere. Therefore, the bishop could relax.

“I went home and basically put the document in the trash can,” this bishop said. “If the vicar for Rome wasn’t worried about it, why should I get worked up?”

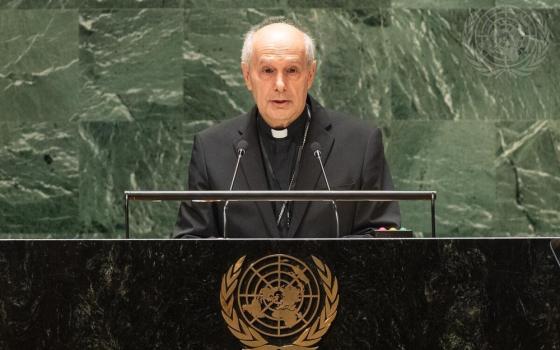

For the moment, the point is not to debate the wisdom of that reaction. It’s rather to observe what it says about Ruini’s singular status: Because he runs the shop in “the pope’s backyard,” Ruini’s every word and deed becomes a sort of informal hermeneutic about what the mind of the pope and the Vatican actually is. That doesn’t mean everyone takes their cue from him – even within the Italian conference, some strike a different tone. Nevertheless, Ruini’s actions carry an emblematic weight that few others can rival.

His comments at this week’s meeting of the Permanent Council of the Italian Bishops’ Conference are thus worth noting, and not merely for their implications for Italian politics. The Permanent Council meets three times a year, and Ruini’s prolusione, meaning his major address, has become a routine staple of front-page coverage in the Italian press.

Ruini’s message this time boils down to a resounding “no” on several hotly contested moral issues, most notably euthanasia.

In Italy as in most other places, debate is raging today about the extent to which patients, through instruments such as a “living will,” should be able to give instructions about the discontinuation of medical care. In the clearest possible terms, Ruini said that no one – including the patient – has the right to will death directly.

“The will of the sick person, either expressed in the moment or given in advance, or provided through a freely chosen person of trust or through the family, cannot have as its object the decision to take life,” he said.

Ruini cited a “broad consensus” against euthanasia, “whatever its motives or its means, whatever the actions or omissions adopted towards the end of obtaining it.”

Ruini did distance himself from what the Italians call accanimento terapeutico, which generally means an over-zealous course of medical treatment which prolongs suffering after all hope of recovery is lost. At the same time, however, that distinction came with a warning.

“Renouncing accanimento terapeutico,” he said, “cannot become a means of legitimizing more or less masked forms of euthanasia, and in particular, ‘therapeutic abandonment.”

Italy has recently been rocked by the case of Piergiorgio Welby, an advanced muscular dystrophy patient who died on Dec. 20 after being removed from a respirator by his own request. Ruini became part of the story when he refused requests for a church funeral for Welby on the grounds that his death amounted to a suicide.

In his speech, Ruini acknowledged that he “suffered” in making the decision.

The funeral ban, Ruini said, “was born with the fact that the deceased, up to the very end, persevered lucidly and consciously in the will to take his own life. In those circumstances, any other decision would have been impossible and self-contradictory for the church, because it would have legitimized an attitude contrary to the will of God.”

Ruini also opposed calls for legal recognition of same-sex unions, arguing that property and inheritance rights can be handled through common law, without the need for new models that “would configure something similar to matrimony, where rights are not accompanied by corresponding duties.”

Gay marriage, Ruini said, “contrasts with fundamental anthropological facts, and in particular with the absence of the good of the generation of children, which is the specific rationale for the social recognition of matrimony.”

Ruini also briefly touched upon the always-volatile theme of immigration, speaking in support of immigration proposals that would favor keeping families together, but also insisting that immigrants must conform “to the values of the society which hosts them.”

As is inevitable in a complex global religious institution, not everyone at the senior levels of the Catholic Church will necessary agree with all the particulars of what Ruini had to say – both in terms of content and tone. Given the unique role he plays in Catholic affairs, however, you can bet they’re at least paying attention.