Demonstrators clash with security forces near the Juliaca, Peru, airport during a Jan. 9 protest demanding early elections and the release of jailed former Peruvian President Pedro Castillo. (OSV News/Reuters/Hugo Courotto)

The Peruvian government has responded with violence in recent weeks to massive demonstrations in several cities against President Dina Boluarte. The number of deaths has reached at least 60, and more than 1,200 people have been wounded during the marches.

While protesters have reported police misconduct across the South American nation, most of the violence has been concentrated in the Andean region of Puno, where 23 people have been killed — 19 of them in a January protest in the city of Juliaca, a transit hub near the border with Bolivia.

Church-run organizations are now pressing the authorities for justice and demanding an independent inquiry be conducted by an international committee formed by experts in police violence.

The crisis first erupted after President Pedro Castillo was impeached and arrested on Dec. 7. After a disputed election against right-wing candidate Keiko Fujimori — the daughter of Alberto Fujimori, who ruled the country with a strong hand from 1990-2000 — Castillo had taken office in July 2021. He faced stiff opposition in Congress, and was impeached after trying to dissolve the institution and rule by decree.

Boluarte had been serving as Castillo's first vice president and is now Peru's sixth president in five years.

Castillo left government with low support in most of the country, but in some Andean regions, especially Puno, many people feel betrayed by the political system — and by Boluarte's changing stance on the crisis.

"In Aymara culture, a pledge has much significance. Boluarte had said in a rally that she would leave the government if Castillo was ousted. She not only failed to leave, but also joined the far right," Fr. Luis Zambrano, vicar of a parish in Juliaca and a longtime human rights champion in Peru, told NCR.

Anti-government demonstrators protest against Peruvian President Dina Boluarte in Juliaca Feb. 9, amid the worst wave of protests in at least two decades in the Andean country. (OSV News/Reuters/Pilar Olivares)

Hermano Lucho, as parishioners in Juliaca call Zambrano, cited figures that some 89% of voters in Puno had supported Castillo in the 2021 election.

Castillo is from a town in the Andean department of Cajamarca. Like Puno's citizens, he has Indigenous roots and is called by many in the capital of Lima a serrano, a derogatory term for people of Andean descent.

"The people from the Andes are despised by the people from the coast. The current movement has a distinct ethnic component," Zambrano said.

Maryknoll Sr. Patricia Ryan (Courtesy of Patricia Ryan)

Maryknoll Sr. Patricia Ryan, a U.S.-born missionary who lives in Puno, said Andean people for centuries have felt like ninguneados — people who are treated as "nobodies," or belittled or ignored.

"Puno decided to support Castillo due to what he symbolized. He had promised a new constitution in which the people's rights would be prioritized," Ryan, who coordinates the nongovernmental organization Derechos Humanos y Medio Ambiente (human rights and the environment) told NCR.

Ryan said living conditions across Puno have deteriorated in recent years, particularly due to a booming industry for gold and copper mining in the region. Ryan said the nearby Lake Titicaca has been especially affected by contamination.

"Mining is destroying the rivers, which the people see as Pachamama's veins," Ryan said, using the term for a goddess revered by many Andean Indigenous peoples.

In large cities like Juliaca, the unemployment rate has been historically high, and most people do what they can just to make do.

"Seventy or eighty percent of the people here work on the streets, selling things. They do not have savings and depend on their daily work to survive. Even so, they dared to protest," said Zambrano.

A general strike was launched in Puno shortly after Castillo's impeachment in December. In January, the marches began to grow. Edwin Poirè Huanca, a lay Catholic who has lived and worked in Zambrano's parish for 22 years, said that the protests have always had a peaceful nature.

"But on Jan. 6 the people decided to block Juliaca's airport. They were tired of seeing planes coming and going and large companies keeping their operations going during the general strike," he told NCR.

Troops from Lima and other regions were then sent to Puno.

Advertisement

"On that day, 13 people were wounded. The norms that regulate nonlethal police actions were totally disrespected. The policemen would fire from short distance and aim above the waist," said Poirè, who heads a local civic organization called Fe y Derechos Humanos (faith and human rights).

More and more demonstrators had to be hospitalized over the following days. Clashes in Juliaca on Jan. 9 led to 19 deaths.

Zambrano's parish has functioned as a meeting point for the people involved in the protests and for victims' families.

"There has been a great solidarity. People would distribute food, medicines and money to the relatives of the wounded and of the dead," Poirè said.

A new group called the Association of Martyrs and Victims of January 9 was created on Feb. 14, with the goal of demanding a thorough investigation of the security forces' actions.

Human rights organizations have said that there is evidence of several ethical violations, such as helicopters throwing tear gas bombs over the demonstrators and snipers shooting at them with lethal ammunition.

"The people will not accept an inquiry conducted by the government, especially if it does not hold accountable the authorities in the end," Ryan observed. International investigators from prestigious institutions will be needed, she said.

People in Puno renewed their commitment for the protests with a march on Feb. 19.

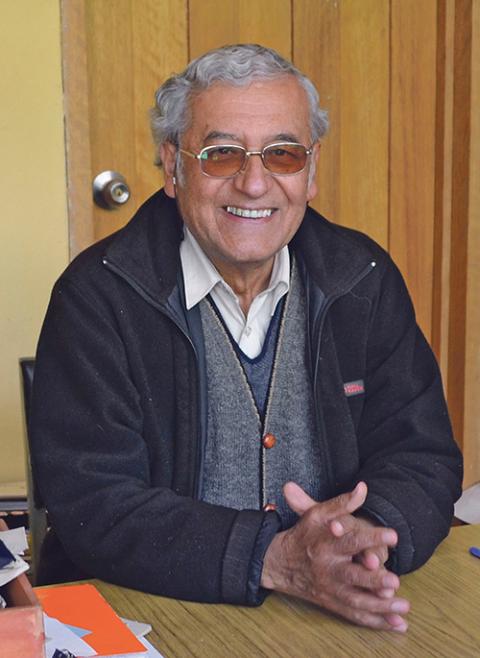

Fr. Luis Zambrano (Courtesy of Luis Zambrano)

"They demand Boluarte's renunciation and new elections for the Congress. They also want a new constitution. But, above all, they want to be heard," Zambrano said.

One wrinkle in finding a solution to the crisis gripping the country is that for many Peruvians, Catholic Church leaders, who might normally be seen as possible mediators, are now seen as biased.

José Luis Franco, a historian and theologian at the Bartolomé de las Casas Institute, in Lima, said the bishops would simply not be able to play a role in any efforts for mediation. He pointed to the bishops' conference's decision to meet with Fujimori but not Castillo during the 2021 election.

Franco called Zambrano a "lonely prophet" in listening to the concerns of the people in Puno.

"He stayed with the people and gave them his voice. He inspired admiration among many," said Franco.

Since the protests began, many media accounts have portrayed the demonstrators as the ones responsible for clashes with the police. Some accused the protesters of being terrorists, which in Peru has a deep historical meaning.

Between 1980-2000, Marxist guerrilla movements like the Shining Path undertook violent campaigns against the country. Their operations and the government's response caused tens of thousands of deaths.

"The people in Puno have always opted for peace. That is the most infamous accusation there can be against us," Poirè said of the accusation that the protesters are terrorists.

Franco sees the current movement as the result of "economic models that do not attend to the needs of the people" and "an administration with certain dictatorial traits, like police abuse."

"But the most important element is that the Indigenous peoples, the peasants from the Andes who have been forgotten by the state for so long, want to take part in the country's political life," he said.