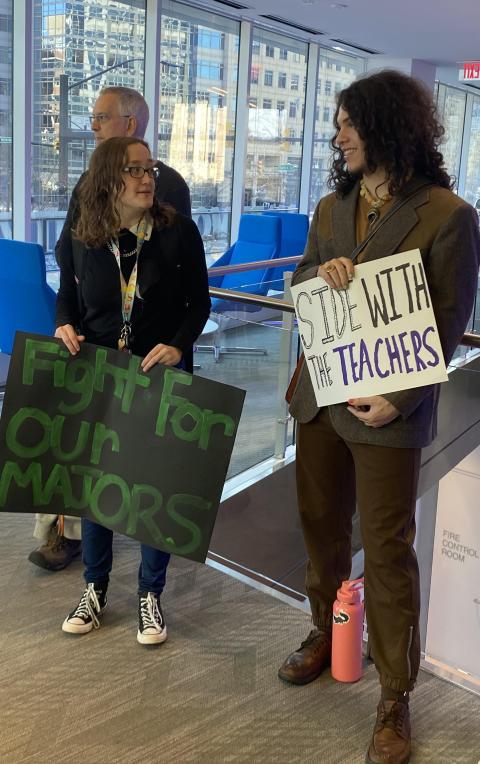

Students protest outside the Marymount University board of trustees meeting Feb. 24 in Arlington, Virginia. (Courtesy of Grace Kapacs)

The unanimous vote by the board of trustees at Marymount University in Arlington, Virginia, to eliminate nine liberal arts majors, most in the humanities, has left sophomore communications major Grace Kapacs "dumbfounded."

While her major won't be disrupted, Kapacs is concerned for fellow students who may decide to leave the school following the trustees' action as well as future students who may bypass Marymount because majors they wanted to study in a rich Catholic setting are no longer available.

"They're all devastated," Kapacs said of her friends majoring in art, history, English and other disciplines. "While they're getting grandfathered in [to graduate in their majors], the legacy and why they came to this school doesn't really mean anything anymore."

Grace Kapacs, a communications major at Marymount University in Arlington, Virginia (Courtesy of Grace Kapacs)

Kapacs, originally from Scranton, Pennsylvania, has been a vocal opponent of the changes as well as the process leading to the trustees' vote. She organized a protest outside of the Feb. 24 board meeting during which the trustees unanimously approved President Irma Becerra's plan to eliminate the majors.

The majors are bachelor degree programs in art, economics, English, history, mathematics, philosophy, secondary education, sociology, theology and religious studies and a master's program in English and humanities.

"These programs are simply not ones that are in demand," Nick Munson, Marymount's director of communications, wrote in an email to NCR on March 7.

He said 74 students are enrolled in the affected programs; 22 of the students are set to graduate in May. This academic year the school has 4,257 students including about 2,600 undergrads.

Becerra has said the school will redirect resources to "areas of growth," such as the nursing and health care fields.

Alumni and faculty also have publicly expressed concern for the decision to eliminate majors that have attracted students to the school since its founding in 1950 by the Religious of the Sacred Heart of Mary.

Students protest outside the Marymount University board of trustees meeting Feb. 24 in Arlington, Virginia. (Courtesy of Grace Kapacs)

Amanda Bourne, who studied English at Marymount, described the plan to end majors "incredibly shortsighted."

"The humanities ... do a good job of teaching soft skills that are invaluable to industries of all kinds," leading to "a well-rounded graduate who can explore a variety of careers," Bourne said.

Marymount's situation is not unique. Officials at St. Mary's University of Minnesota announced in May that 11 majors were being eliminated in the coming years. Among undergraduate programs facing the axe are English, art, history, music, Spanish, theater and theology.

The questions surrounding the future of humanities at the two schools are similar to those being confronted throughout higher education as school officials weigh reshaping their academic offerings in a time of changing student interests.

That fewer students are majoring in the humanities also points to a debate on how well American society understands and values the "thinking" professions that explore human relations and bring meaning to life.

Data compiled by the U.S. Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics show that the number of higher education graduates in the humanities has declined by 29.6% from 2012 to 2020.

The center's Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System reveals that 2020 marked the eighth consecutive year the number of humanities graduates declined. In 2012, schools reported 117,351 humanities graduates. The number fell to 82,646 by 2020, the most recent year for which data has been released.

The data show that some schools — including Catholic institutions — recorded steep declines in the humanities during the period.

For example, the data show the University of Notre Dame with 50% fewer humanities graduates. Other Catholic schools, primarily small institutions, reported declines as steep as 93%.

Some institutions, such as Marymount University ironically, showed no change in the number of humanities graduates from 2012 through 2020. Some — mostly schools with small enrollment with up to about 30 humanities graduates annually — registered modest gains in the eight-year period.

Marymount officials disputed the data reported by the Department of Education showing the number of its graduates in the humanities was unchanged during the eight-year period. The school said its internal statistics reveal a sharp decline in humanities graduates, falling from 72 to 38 from 2012 to 2020.*

The Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, an umbrella organization of some 225 institutions of higher education in the U.S., Canada and a few other countries, does not track data on the kinds of degrees awarded by its members.

But in discussions with various school officials, Vincentian Fr. Dennis Holtschneider, the association's president, acknowledged hearing that interest in the humanities is waning, leading higher education leaders to review which majors are worthwhile to maintain.

"It's not that those schools drop faculty or programs," he told NCR. "It's that the students are dropping the majors."

Some schools have taken steps to combine majors in the humanities to keep programs alive, Holtschneider said. "What they're doing is buying time hoping that this is cyclical. But at the moment there is no evidence that this is cyclical," he explained.

These days, health care, engineering and technology are growing in popularity, Holtschneider said.

Even when majors close, Holtschneider has seen school officials maintain an array of liberal arts and humanitarian course requirements to provide a broad education for students and to keep key faculty on staff.

Going back decades, the humanities have experienced upward and downward swings, largely paralleling economic boons and busts. Even after the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009, there was an uptick in humanities enrollment for a few years. But since 2012, the number has declined even as the economy was strong prior to the pandemic.

Advertisement

Rob Townsend is a longtime number cruncher of the federal data as program director for humanities, arts and culture at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences' Humanities Indicator Project.

He suggested there is a misperception throughout society about the value of a humanities degree as one factor influencing students entering college.

"I feel there's a cultural change that's happened related to higher education in the years since I started thinking about this in the '80s. It's really a shift from the idea that we make society better by having a lot of college-educated people, especially broadly educated people," Townsend said.

"That societal good notion of higher education, I feel, has been replaced in the last 20, 30 years and especially since the Great Recession with this idea of a kind of private good notion of the purpose of higher education. That having somebody get that college degree is good for all the rest of us as well, I think, has largely been lost."

Chris Farnan, dean of the School of Liberal Arts at Siena College (Courtesy of Chris Farnan)

Higher education leaders are striving to instill the idea in students and their parents that education in the liberal arts and humanities will help a young college graduate in establishing a meaningful career.

Chris Farnan, dean of the School of Liberal Arts, at Siena College in Loudonville, New York, said that while the number of humanities majors has declined at the Franciscan school, faculty and administrators continue to stress the value of the arts, history, literature and theology as key to developing the human person.

"Part of our Franciscan learning community is that we are graduating human beings that are going to make the world more peaceable, more just and more humane," Farnan said.

"Liberal arts majors, humanities majors know things. They have an in-depth knowledge of human history. They have read widely and deeply. They have an understanding of the way human beings have related to each other over the course of the development of humankind," she added.

Siena has no plan to eliminate majors.

"Say there is a huge drop in business majors, would we be talking about the death of the business major?" Farnan asked.

At the University of Notre Dame, Sarah Mustillo, dean of the College of Arts and Letters, questioned the federal data on humanities graduates for the school.

She said the university has recorded a 9% decline in humanities graduates since 2012, rather than the 50% figure listed in the Department of Education's data.

"There are fewer students majoring in the humanities compared to 10 years ago, but that to me is a very modest decline. It's not a major change," Mustillo said.

She described the humanities as crucial for developing skills of "critical thinking, articulate speaking, writing well, empathy, being able to work in groups and in diverse teams," saying, "those are essential for the future."

Across the country at the University of San Diego, Noelle Norton, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, also was unsure of federal data that show 44% fewer humanities graduate at the school since 2012. She placed the decline closer to 24%.

Noelle Norton, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of San Diego (Courtesy of Noelle Norton)

"But we still feel it," Norton said.

The university has established a Humanities Center, which sponsors events such as free lectures, panel discussions and student-generated podcasts geared toward helping students understand the importance of a broad-based education.

"We want to make sure that the intersection of the human to science, technology, the social behavioral sciences and the arts is really clear," Norton explained.

Back at Marymount, Kapacs is planning to continue the campaign with other university partners to convince the school's administration to look for other areas to reduce costs and keep the humanities majors in place.

"This is a Catholic institution built on the liberal arts core," she said. "For our university to make those decisions, it's not meant for us."

*This paragraph was added after the story's original publication.