Guadalupe Lara in her home in Guadalajara, Mexico, with a copy of her memoir. A framed photograph of the historic Arcediano Bridge, which was destroyed during dam construction, rests at her side. (Tracy L. Barnett)

Once Guadalupe Lara was surrounded by forests, farms and friendly neighbors. Now she's surrounded by cement in a metropolitan area of 5 million people, with barely a tree in sight.

It's a hard life for this tiny woman, now 70, who stood in the way of a multimillion-dollar dam project — and lost everything she owned in the process. Together with community organizations, she succeeded in stopping the dam. But her entire village was razed, and now, more than 15 years later, she continues the fight for justice.

She fills her apartment in Guadalajara with plants and with birds, and she's grateful to the benefactor who pays her rent. But she struggles with poverty, frequent migraines and depression. She lends her presence to the struggles of others who are fighting a similar fate — most significantly, the fight to stop El Zapotillo Dam, another project from the same government agency that forever changed the course of her life.

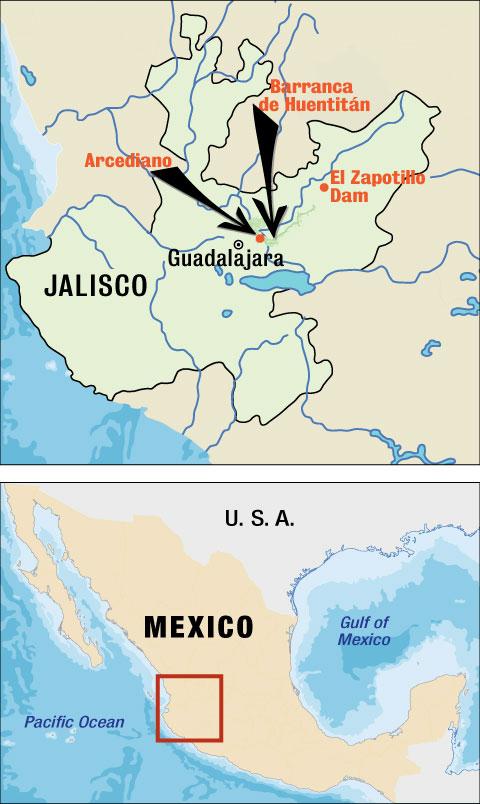

Lara grew up in the town of Arcediano at the bottom of the Barranca de Huentitán, a vast and dramatic Grand Canyon-like gorge at the edge of Guadalajara, the bustling capital of western Mexico. Despite growing up in poverty, she recalls many happy memories rambling through cornfields, collecting mangos along the Santiago River, attending the village school and church.

Raised as one of six, caring for their mother and their corner store, she never married. One day, a group of Franciscan nuns visited her town, and she became intrigued with the religious life. Her sister joined the order, but Lara felt uncomfortable with wearing a habit and living in a convent — the only options she knew for a woman religious.

Years passed. She was invited to a retreat at the Secular Institute of the New Man in Guadalajara, where she met the founder, Fr. Arturo Martín del Campo Medina. The vows she eventually took, along with others from her institute, were the same as those of her Franciscan sister: chastity, poverty, obedience. As a consecrated lay woman, she found a way to stay in her beloved village and care for her mother, while still being a woman religious.

The vow to defend her community and her habitat, as she calls it, would come much later. But it would affect her life just as deeply.

"Temaca, You Are Not Alone": Guadalupe Lara holds up a sign in defense of Temacapulín, another Jalisco village threatened by a dam, at July 2019 press conference in Guadalajara by the Mexican Institute for Community Development. The institute accused the government of following inequitable water management policies. (Tracy L. Barnett)

It began in 2002, when a letter arrived saying the government was planning to build a dam that would flood the isolated little village, a project aimed at providing water for the city of Guadalajara.

"They said, 'You all will be taken away from here,' " said Lara. "So I decided to be brave and I began to do a survey about who wanted to be moved out of there, and everyone said no, and put their signatures on a sheet. And being a busybody, I began to get involved in those things."

The residents of Arcediano were not alone in their opposition. Environmental and civic groups opposed the dam for many reasons, among them the destruction of the town and a federally protected reserve, as well as the severe industrial contamination of the Santiago River.

"It was an absurd project, ridiculous, illogical," said María González of the Mexican Institute for Community Development. "In a river that is highly toxic in a zone with social conflict, where the people are sick and die from this water — it was to construct a dam for this water so the people of the city of Guadalajara could use it for its water supply."

Manuel Villagómez Rodríguez, former state representative and a founder of the Citizens Observatory for Water, called the entire four-dam project, as conceived by the Jalisco state government and private interests, "a monument to corruption."

"It's the biggest mistake that has been committed in these 21 years by those who think more about the business of privatizing the water ... than in the collective interest," he wrote in his book, Falacias del Proyecto de Abasto de Agua Para Guadalajara ("Fallacies of the Water Supply Project for Guadalajara").

Guadalupe Lara in front of her home in Arcediano, Mexico, before it was razed (Provided photo)

In September 2002, Lara wrote to newspapers expressing the community's opposition, prompting visits by a news crew and representatives of a nonprofit. She read her letter to the group and was roundly applauded.

She quoted community members saying, "We're going to make Lupita [Guadalupe] the president of an organization." She demurred, but they insisted.

"They told me that I was very spirited, and they were going to leave it to me, whether I wanted to or not, and they put me as president with a board of directors."

She drove up and down the canyon day after day for meetings and interviews. She became active in the Mexican Movement of People Affected by Dams and in Defense of the Rivers. She traveled to Oaxaca, Puebla and other places where people were fighting dams. The politicians and businesspeople behind the dam began taking aim at her. Dam supporters told her she was being manipulated by Villagómez and other opponents for their own political purposes.

Seated at her kitchen table in the same apartment Villagómez has rented for her for 15 years, she opened the floodgates to a deluge of memories.

"Oh my God. I cried a lot, I prayed a lot, I suffered a lot, and still do, to this day," she said. "I swear, if they asked me again, would you lead another fight? I really don't know."

She began to suffer severe migraines. The pressure increased. The government sent officials to speak with village residents, offering money, new houses, whatever they wanted. People were told they had to leave, and if they didn't accept the money, they would be left with nothing. She said the community began to turn against her.

Advertisement

"I discovered that my neighbors lacked courage and had a panic of those in government, thinking that their word is the word of God," Lara wrote in her 2014 memoir, I Saw My Village Weep: Stories of the Fight Against the Arcediano Dam. "I lost friendships with everyone."

People told her to stop being stupid. " 'Do you think you're going to beat the government? They can kill you,' they told me. I said: 'Look, we were born to die, and then what?' "

She said government representatives and reporters asked her: "How much money do you want, ma'am? Don't you want to leave?"

Lara recalled answering: "Look, my fight is not for money; my struggle is for my land, for my habitat, for my dignity, for the corruption of these dirty governments. If it were for money, I would have left. ... I want to fight this thing to the finish. I told them that, so I ended up without my land or my house or my business being paid for. Unbelievable."

She divided her time between the city and her little brick house in the village, surrounded with fruit trees and flowers, and tried not hear when bulldozers began cutting through the hills.

"The media came almost every day to my house to get news, and my family put me in front," Lara recalled. "You busybody, you gossip, you're the one that's all into politics, go ahead!"

Under constant pressure, nearly half the families signed away their homes and received their money, and the bulldozers began tearing down the houses. Her brother came to her: "Andale, Guadalupe, let's sign the papers and be done with this."

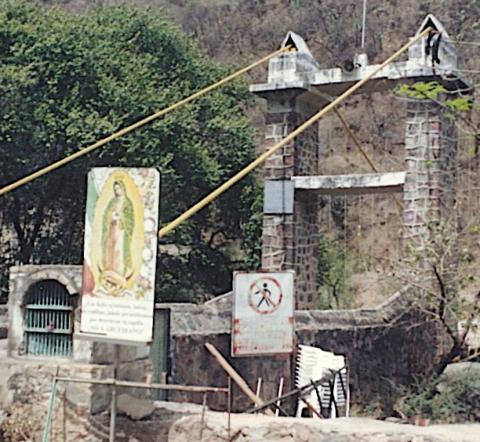

The historic Arcediano Bridge, the first suspension bridge in Mexico and the second in the entire hemisphere (preceded only by the Brooklyn Bridge in New York), was destroyed for dam construction. (Provided photo)

She refused. Her family left, and their houses were torn down, too. Then it came time for the school, and then the little chapel, with the framed picture of the Virgin of Guadalupe, who had always sustained them during the hard times. And finally, one day when Lara was gone, they bulldozed her house, too.

A friend called and told her the next day. "I knew that was going to happen — but I didn't know it was going to hurt so much."

She couldn't bear to see it, but she had to go to file a claim. "I don't know where I got strength, but off we went. ... The only thing I found was a little image of the Virgin of Talpa, thrown on the ground."

Lara's mother, who moved into the apartment with her, was devastated. She developed dementia soon afterward and didn't live long. Many elders from her village suffered a similar fate, and people of all ages suffered displacement trauma.

"Some people died of sadness," she said. "'This is not my home, my home is the canyon, let's go,' they'd say. Well, can you imagine? There are no houses left or anything, but they carried their land, their roots in their hearts."

Most families were offered the equivalent of U.S. $18,000 for their family patrimony — enough to buy a small house in the city. "And apart from that, what were you going to live on? You were not prepared, you had no studies, you had nothing. So they took you to die in the outskirts of Guadalajara."

After nine years of legal and political wrangling and more than 700 million pesos spent (around $36 million today), the Jalisco government decided to cancel the Arcediano Dam in 2009. The village of Arcediano was nothing but an overgrown plain of rubble. It remains so today.

With Villagómez's support, Lara filed for compensation, but was denied on the grounds that it was too general, that she had waited too long to file, and that she had been offered compensation before but had refused. She has filed a new claim under the new government. As of yet, she has received no response.

"Guadalupe Lara is a living monument of human dignity," said Villagómez. "It is frustrating that her struggle is ignored by the authorities and also by those who benefit from her struggle."

In the intervening years, Lara has continued to find strength in her faith. "I was neither a leader, nor a great character, but only a person consecrated to God, and that was where I found strength and courage," she said. "Sometimes when the world is very dark, very cloudy, when you can't see forwards or backwards, you say: Oh my God, I would rather no longer exist! Don't go saying that, they tell me, but those are your dark moments. But there is God, and he lifts you up, he protects you, he sets you free, he gives you grace, and that's how we are able to keep on going."

Lara has lent her support to many communities fighting destructive megadam projects. In particular, she has been a strong supporter of the village of Temacapulín, currently fighting obliteration by El Zapotillo Dam.

"I always try to share the story of our struggle, so that it doesn't happen to them," she said. Her advice, born of the mistakes made by her own village: Stand together, and fight for your rights.

González and Villagómez say her role was key to the Arcediano Dam's eventual cancellation.

"Doña Lupita was the heart of the struggle," said González. "The other organizations, academics, collectives, contributed other elements from our experience or capacity or knowledge — but what linked us to the territory, the identity, the love of the land and the community of Arcediano was always Doña Lupita Lara."

[Tracy L. Barnett is the founding editor of The Esperanza Project, a bilingual online magazine covering social change initiatives in the Americas. You can read this story in Spanish here.]