(Dreamstime/Roman Samborskyi)

One Sunday afternoon in October, Mariana Cano Rodriguez and Nancy Martinez Hernandez were out in Milwaukee's Mitchell Park, not to run or relax but to register people to vote.

The two teens, 17-year-old seniors at Cristo Rey Jesuit High School, can't yet cast their own ballots, so they and three of their classmates asked those who can in the battleground state of Wisconsin to do so on their behalf.

"Their decision, they may think it's small, but it does impact the way our country is going to run the next four years ... not only our country, but other countries. So I think that's important to me," Cano Rodriguez said.

Atop the two students' issues, if they had a vote, are immigration and health care. But also of concern is the environment, and specifically climate change.

"It's going to impact us negatively in the next few years if we don't do anything about it. And it's caused many natural disasters," Cano Rodriguez said, referencing the recent hurricanes that tore through the South.

The Cristo Rey students spoke with more than 100 people outside the park's kaleidoscopic greenhouse domes three weeks ahead of Election Day for the event partnered by Catholic Climate Covenant. Most were already registered. One wasn't, and signed up.

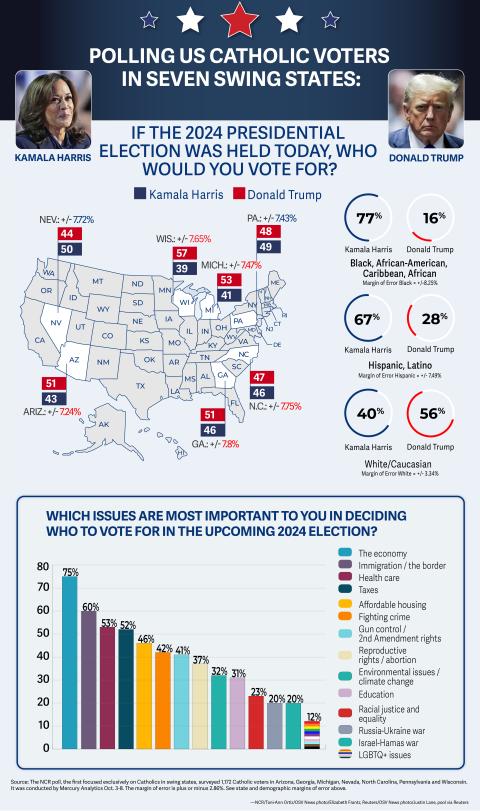

Polling suggests a tight outcome in the presidential election between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump, meaning any number of narrow voting segments could prove decisive in the seven battleground states: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

Jonas Reyes Jimenez, Mariana Cano Rodriguez and Nancy Martinez Hernandez stand inside one of the greenhouse domes in Mitchell Park in Milwaukee on Oct. 13. The students at Cristo Rey Jesuit High School sought to register voters for the 2024 election as part of an event in partnership with Catholic Climate Covenant. (Benjamin Rangel)

Environmental voters are one of those. That is, if they vote.

In the 2020 election, a record turnout of 154.6 million Americans — two-thirds of eligible voters — cast ballots. On the flipside, 77 million eligible voters did not.

More than 8 million of them were environmentalists, according to the Environmental Voter Project, a nonpartisan group whose mission is to identify low-propensity voters who care about the environment and motivate them simply to head to the polls.

This year, the Environmental Voter Project has targeted reaching 4.8 million infrequent voters in 19 states. In an Oct. 31 briefing on early voting data, 335,500 of their targets have already cast ballots. That includes 45,000 in Georgia and more than 13,000 in Arizona — both higher than voting margins President Joe Biden won in 2020 to carry each state.

The Environmental Voter Project recruits volunteers to contact would-be environmental voters through phone banking and door-to-door canvassing. Among the groups partnering with the organization this year is GreenFaith.

"We don't usually focus on voting as an organization, but given how very important it is, we felt that we needed to put some energy towards this this year," said the Rev. Amy Brooks Paradise, a Unitarian Universalist minister and GreenFaith's North America organizer.

"[Climate change] is a situation that is urgent — some people would say dire and even an emergency," she added. "And the fact that this is not front and center in our political conversation is really sad."

Polling has shown the environment and climate change low on voters' priorities this year. In an October poll by National Catholic Reporter, 32% of Catholics in battleground states listed climate change and environmental concerns as important in deciding their vote, ninth of out 14 possible issues. The economy (75%) and immigration (60%) were at the top.

Female and Black Catholics were more likely to list the environment as an issue, as were those with a favorable view of Pope Francis, who has made environmental concerns a central pillar of his papacy. Roughly half of likely Harris voters listed the environment as a voting issue, compared to less than a quarter of likely Trump supporters.

While climate change has received scant attention from candidates and voters, the outcome of the presidential election will have far-reaching implications for national climate policy at a critical juncture. The next U.S. president will be in office for much of the rest of the decade, a period during which climate scientists say global greenhouse gas emissions must be nearly halved in order to hold global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

A new United Nations report found that nations' cumulative climate plans would reduce global emissions by only 2.6% by 2030. A report from the World Meteorological Organization found greenhouse gas concentrations at their highest level on record.

Harris has said she will continue implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act, the nation's largest-ever climate law that is directing more than $360 billion toward clean energy and other projects aimed at slashing national emissions.

Trump, who was twice impeached while in office and faces criminal charges for his efforts to overturn the 2020 election and for his role in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection, has touted a refrain of "drill, baby, drill" and has called climate change "a hoax." He has pledged to again withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement and undo parts of the Inflation Reduction Act, including tax credits for electric vehicles.

The stakes of what the election outcome will mean for climate change has led GreenFaith to host phone banking sessions every Thursday since September through the Environmental Voter Project, which provides the contact lists and scripts. Several dozen people have joined a Zoom room set up by GreenFaith that begins with grounding voter outreach in spiritual terms. Volunteers then make calls for an hour before debriefing afterward.

Together, GreenFaith phone bankers have made more than 1,000 calls, with a single person able to conduct between 30 and 40 calls in the hour session. Not all calls end in answers.

Advertisement

When people do pick up, the conversations are nonpartisan, with the sole goal to provide the person on the other end the information, and a push, needed to vote before or on Nov. 5.

Maria Wood, a history graduate student at St. John's University, in New York, spent her Halloween night phone banking with GreenFaith. It was the second session for the 25-year-old Catholic from Wisconsin.

"I really liked that integration-of-faith aspect, because those other phone bankings I'd done didn't have that. And I thought it was refreshing and left me much more energized," she said.

The environment is a "huge concern" for Wood, and helped her decide to cast her mail-in ballot for Harris.

Wood learned of the phone banking opportunity through her Vincentian Encounter group, a young adult program of the Daughters of Charity that focuses on integrating work and Catholic social teaching. Wood's group recently discussed integral ecology— a concept the pope highlighted in his encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" — and phone banking with GreenFaith was presented as a way to put that idea into action.

Phone and text banking are seen as more efficient ways to reach voters, though less effective than door-to-door canvassing. Many calls end quickly or catch people weary at the end of the day. In one call, a woman whose bread was burning in the oven asked Wood to call her back.

"You don't want to take up too much time, but you also want to get out the most important information, which is, please go vote. Here's how you can vote," said Wood, who has text banked with voters in Wisconsin, Tennessee and Georgia.

In a separate campaign, members of Georgia Interfaith Power and Light have sent an estimated 800,000 text messages to people in the Peach State encouraging them to vote and providing information on how to do so, according to the group's organizing director, Marqus Cole. The text banking, in partnership with ProGeorgia, has focused on turning out voters in the five counties around Atlanta, as well as around Savannah and Augusta.

Members of Georgia Interfaith Power and Light take part in a text banking session in October in Savannah. (Courtesy of Georgia Interfaith Power and Light)

"With the extreme weather going on now, more than ever, this message of voting around environmental issues was really key and important to us, so we have had a chance to engage our community to take a step up in advocacy," Cole said.

Georgia proved critical in the eventual passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, not only in placing Biden in the White House but in giving Democrats 50 seats in the Senate, enough to allow Harris as vice president to cast the tie-breaking vote to pass the climate law.

"These policies don't happen if people don't vote their values and get people in that want to see those policies passed," Cole said.

Unlike the Environmental Voter Project phone banking, Georgia Interfaith Power and Light members introduce themselves in the texts as a person of faith who cares about environmental issues. Along with providing voting information, they also direct people to a voting guide on its website.

In Georgia, Wisconsin and Arizona, state chapters of Interfaith Power and Light have perceived high levels of enthusiasm among voters, though mixed with some fatigue.

And while climate change hasn't rise to the top of concerns for voters they've engaged this year, in places like Phoenix, which faced a historic summerlong heat wave, it's still "more present in their minds often," said David Coatsworth, a member of Arizona Interfaith Power and Light who's done phone banking for the Democratic Party.

"To say that it's the top issue, for most of us it's not directly hitting our pocketbooks to the extent that job loss and other factors do," he said.

Cole, too, has sensed a motivated electorate in Georgia, pointing to record-breaking ballots cast on the first day of early voting — doubling the total from 2020. That enthusiasm extends to Black churches, which he said have "a long history of understanding the connection between faith, values and voting."

"We can't talk about our faith without talking about environmental issues, whether that be environmental justice or care for God's creation," he said.