Pope John XXIII leads the opening session of the Second Vatican Council on Oct. 11, 1962, in St. Peter's Basilica. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano)

I was about 10-years-old when the phrase "Vatican II" first came into my consciousness. My family was in its regular pew at St. Joseph's parish, and I was in the daze that accompanies elementary school children during Sunday Mass. When I heard the priest say my mother's name, however, I snapped to attention.

"It's called the Sign of Peace," he was explaining, his Irish lilt floating over us as he gestured toward my family. "Mrs. Schafer will turn to Pamela and shake her hand, then Pamela will turn to Renée and offer the same, then Renée will offer the peace to Bryan." To my absolute mortification, he then instructed us to demonstrate what he'd described for the benefit of the rest of the congregation.

Advertisement

A few years later, the council's changes once again came into my small world. I'd been called to the principal's office for a reason unbeknownst to me, but that I suspected might have to do with the fact that I'd spearheaded a drive to let us eighth grade girls wear our uniform skirts two inches shorter than currently allowed. As I knocked on Sr. Mary Margaret's door, I readied myself for a reprimand.

Instead, she produced a cassette player, popped in a tape by The St. Louis Jesuits and I heard my first "folk Mass" rendition of the Lord's Prayer.

"Father wants this added to our school Masses," Sr. Mary Margaret said, "and your teacher says you play guitar." She handed me the sheet music and told me I'd be teaching it to the rest of the school that Friday.

And so, rather horribly that first time, I played the song, our parish organist grimacing in the background, Sr. Mary Margaret looking as if I was personally re-crucifying Jesus, Fr. McCarthy and the school's young nuns beaming like they'd won the lottery. A year later, we had a full band at school Masses.

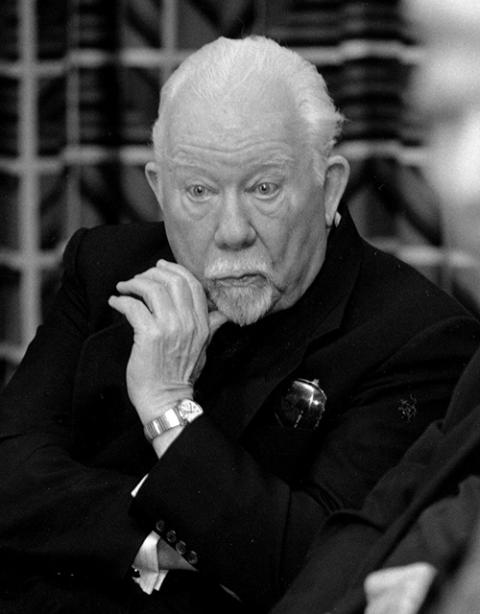

Redemptorist Fr. Francis Xavier Murphy, pictured in a 1996 file photo, wrote a series of dispatches on the Second Vatican Council for The New Yorker magazine. Written under the pseudonym Xavier Rynne, his "Letters From Vatican City" caused a sensation by offering a behind-the-scenes look into the secret proceedings. (CNS file/The Catholic University of America)

These incidents will seem minor to younger Catholics who've only experienced liturgy in the vernacular, altar girls, ecumenical prayer services, a drum kit in the choir loft and catechesis that no longer says Jews killed Jesus. But as I read The Mole of Vatican Council II: The True Story of "Xavier Rynne" by Richard A. Zmuda, I shuddered to realize how close the church came to never having any of those things.

The book is sold as historical fiction but reads more like a history book in many chapters, which, incidentally, is a strength in this case. It details at length desperate efforts by Curial traditionalists to sabotage the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) to "save the faith" — and how close they came to achieving that objective.

The heart of the novel, however, traces those traditionalists' frantic attempts to unmask and silence a priest who, under the pseudonym of Xavier Rynne, wrote a series of eye-popping articles for The New Yorker spilling the beans on backroom dealings and attempted subversion of the goals Pope John XXIII and his successor, Pope Paul VI, had for the council.

Fr. Francis Xavier Murphy was an American Redemptorist priest serving as a theological adviser to a Redemptorist bishop during Vatican II. This allowed him access to all sessions, as well to the hallways and elevators where he learned of efforts by Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani and other conservative prelates to undermine the council. The novel details how Murphy became Xavier Rynne, how his articles became must reads for lay Catholics and clerics alike and how he became the target of Ottaviani and others' rage.

The Mole of Vatican Council II has its strengths and weaknesses. Zmuda, who has written two non-fiction books for cancer survivors, shines in the sections that are steeped in historical fact. His writing is less convincing in the novel's two primary subplots, both involving female characters: an almost-romance and an adoption scheme. In the former there's far too much winking and stilted dialogue; in the latter, there's some teetering into the "White Savior" trope. Zmuda explains in his epilogue that the two women are "fictional characters considered essential by the author to the overall storyline," but those scenes feel almost shoe-horned into the book, stopping its generally fast-moving pace.

Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, left, stands next to Pope Paul VI, center, in this photo taken sometime between 1963-1965 during the Second Vatican Council. (Wikimedia Commons/Lothar Wolleh)

Despite the author's insistence in the book's forward that The Mole "should be read as historical fiction," both the forward and epilogue let readers know that most of it is based on primary source documents: Murphy's articles, diaries, personal letters, interviews with Columbia University's Oral History Research project and even files secretly kept on Murphy and given to Zmuda by anonymous sources. The primary sourcing makes the book more interesting than it might otherwise be, but also more frightening; readers get a close-up view of how important — and precarious — that time in church history was.

There are also parts that read as if they could be happening today. For instance, a quote from Pope Paul VI saying the Curia "… should now be simplified and decentralized …" could be Pope Francis speaking any day of the week. The parts about traditionalists thinking Mass in the vernacular is a fast-track to hell could be lifted directly from the social media feeds of a few ultra-conservative bishops right now.

The Mole of Vatican Council II is an entertaining and illuminating read overall, but readers should go into it knowing it won't read like most traditional historical fiction. It is for Catholics who like inside-baseball analysis, for non-Catholics who crave the "fly on the wall" experience of an institution that still holds sway in the world and, dare I say, for every person who never wants to go back to where we've been.