To say that Fr. Lou Cameli’s new book, The Archeology of Faith: A Personal Exploration of How We Come to Believe, is charming would not be wrong, but it would be inadequate. Charm suggests an affectation, something on the surface, and it sometimes masks uglier motives. The Archeology of Faith has its charming moments, but it brings the reader deep into one man’s story of faith, which he traces back more than 2,000 years.

As the title suggests, Cameli digs into his family’s past to see how it was that he came to be baptized into the Catholic faith in a parish in Chicago in the twentieth century. And, he makes it clear that his foraging in his own past is undertaken with a purpose: “In our time and culture, as I perceive it,” he writes in the introduction, “the faith that nonbelievers deny and that fundamentalists affirm is a flat reality. It is one-dimensional. Genuine faith, in stark contrast, is complex, richly textured, and always deeply human, even as it moves beyond itself and connects with divine transcendence.” Cameli finds this more complex and more human experience of faith in its “complexly layered history.”

Cameli’s archeological enterprise begins in the Iron Age, around the sixth century BC, perhaps even earlier, in the town from which his family came, Grottommare, in central Italy, on the Adriatic coast. He recounts a visit to his family’s hometown when his cousins brought him to the church of San Martino which, at first glance, appeared to be like many other graceful churches that dot rural Italy. “Then, I did a double take,” he writes. “Jutting out over the door of the church was a large, marble foot – just a foot jutting out and very obviously!” Here was the last vestige of what was once a temple to the goddess Cupra, a local goddess of fertility. His next observation shows the cultural dexterity and spiritual attentiveness that pervades the entire text: “For agricultural people, as the Picentes were, the cult of Cupra promised some mastery over the uncertain forces of nature and, ultimately, the prospect of a sufficient harvest to guarantee survival.”

In each chapter, Cameli concludes with observations that relate to his own sense of faith, and regarding the once sacred foot, he writes, “The pagan roots of my Christian faith are really the human foundations of faith. There is something in the human spirit that rebels against being subject to arbitrary forces. That human spirit intuits even obscurely a transcendent and even protective presence at work in our lives.” It goes without saying that this is the observation of a man who is not made afraid by experiences that do not cohere with every jot or tittle of the catechism.

Which is not to say that anyone can find a sentence in this book that is not pervaded by a deep commitment to the Catholic faith that catcechism seeks to explain. In reflecting on the early Christian missionaries who came out from Rome to the region of Grottommare, Cameli writes, “At some point, missionaries came to Grottammare and to my ancestors. Most likely, they came from Rome and across the peninsula on the Via Salaria. I cannot know the exact time they came, and I do not know their names. I do know that they came. And they made the journey on a road constructed by a regime hostile to the Christian faith….Across two thousand years, the Word of life and the summons to faith have been handed on from one generation to the next. Across the great chain of witnesses, in the end, they have finally arrived into my life. And I, too, have the responsibility to continue this handing on, so that eventually generations unborn will be able to know about Jesus Christ and then believe in him.”

The reader is introduced to Emidio, a bishop, martyr and saint, who came to the region around Grottammare in the late third century and who was martyred sometime between 305 and 309. Cameli tells his tale and points to its importance in his own understanding of faith: “For me, this layer of my faith history corrects a frequent misperception of faith. Many people think that faith makes life easier and simpler, that it has a soothing effect. In fact, almost inevitably, faith shapes choices that will set us in contrast to our world and, sometimes, even to our closest relationships. Ultimately, faith brings us and our world to a fulfillment beyond our imagination, but the way of faith has its struggles and complications.”

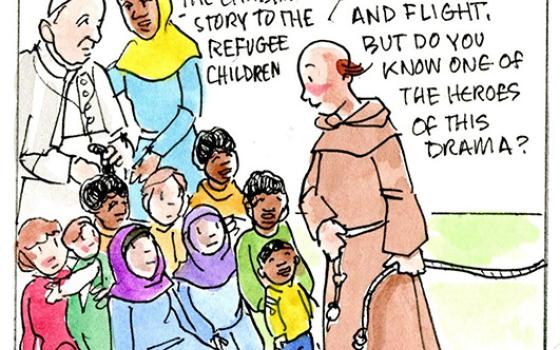

Cameli writes about the Saracen pirates who came to the area in the early Middle Ages, the natural and understandable conservatism of a rural populace that makes its living from the land, the Franciscans and their profound effect on the religious life of Italy. On this last point, he observes:

Church history records many spiritual movements of renewal, and they often followed their own path apart from the Church and sometimes even in opposition to the Church. It could not be that way for Francis. From the beginning of his conversion, he sought out his bishop. As he organized his brothers, he sought approval from the Holy Father. His renewal stemmed from the Church and was always meant for the Church, and it would unfold in the Church.

Today, how similarly these words apply to the first pope named Francis.

Subsequent chapters look at the Inquisition and Counter-Reformation, the Enlightenment and Romanticism, the immigrant experience and, finally, Cameli’s own life, first as a young Catholic whose world was permeated by the sounds and symbols of the Catholic ghetto and, later, as a priest whose scholarship and ministry both led him beyond the walls of that ghetto, but always with an appreciation for that world he was transcending.

Tomorrow, I will take this conversation in a different route, focusing on faith itself and how, too often, we replace faith with some other framework that distracts or distorts the Church from Her truest self and most sublime vocation. For now, it is enough to say that Cameli’s book invites us to think more deeply about what faith is and how it is transmitted from age to age, always under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, but nonetheless a deeply human reality and experience. And, this book does so in a very accessible way. Catholic book clubs, RCIA programs, adult faith formation, all could use this book to begin important conversations about faith. It is a light read, but only at first glance, for the questions raised, the long story of how this one man’s faith came to be offered, and claimed, by him, all give testimony to a persistent, real, varied, and sometimes turbulent faith through the ages, a real faith, a deep faith, a lived faith.