Catholic social teaching, which deals with matters of poverty, wealth, economics and race, is found in the writings of popes and other bishops and often comes out of the reflections of Catholic theologians. These date back to the late 19th century and continue to develop.

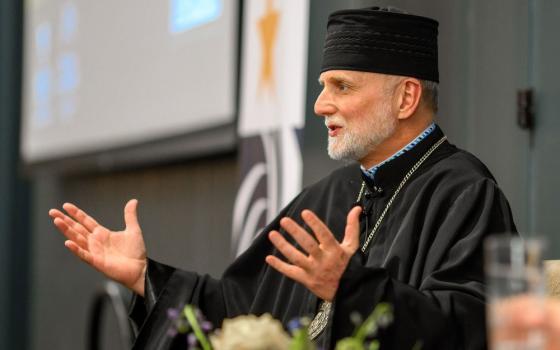

Speaking at the Catholic Theological Society of America’s annual gathering June 13, Fr. Bryan N. Massingale, professor of theology at Marquette University and the society’s outgoing president, challenged his colleagues to consider further development by examining the cultural roots of racism in America and the perceived threat to white identity.

Rather than seeing our nation’s racial issues as somehow “settled” with the achievement of the election of its first African-American president, he suggested racism is with us and could get uglier as European descendants lose their majority status -- and attempt to grip on to power.

His warnings are timely. To understand this, one only needs to look at the bewilderment, anger and racism that characterize much of the tea party movement. Meanwhile, antigovernment, anti-Obama white militias are reportedly growing.

In Massingale’s presidential address, he argued that not only blacks, but whites as well, are victims of our nation’s shameful slavery history. Black anger remains real; white racism can exist even in denial.

Using Malcolm X, whose life ended with a shotgun blast to the chest in 1965, as a focal point, Massingale challenged his colleagues to better understand the thinking of the nation’s marginalized black Americans and how this thinking could relate to Catholic social thought.

Catholic social teachings avow, he said, that solidarity is not merely a vague sympathy for another’s plight. Rather, he said, Pope John Paul II taught that solidarity is a commitment, a “firm and persevering determination” to act on behalf of the common good, and preferentially for the good of the poor.

But is this enough? As a church, do we adequately understand the mindset and, thus, the self-identity of those most affected by racial prejudice? And if we lack proper understanding, can remedies be properly directed?

“I argue,” said Massingale, “that without a deeper, more intentional dialogue with the entirety of the black experience and the whole range of black thought (not simply with that which is considered tame or acceptable), the church in the U.S. and its theologians cannot and will not adequately and justly rise to the challenge of this hour. To put it bluntly, Malcolm’s thought reveals how and why we are about to face a crisis of unimaginable import in the next decade as the church (and society) navigate a profound demographic shift.”

Continued Massingale, “Malcolm would judge the solidarity advocated by Catholic social ethics as unrealistic (if not ideologically complicit) in its assessment of the difficulty of achieving social change. It underestimates both the recalcitrance of the privileged and the potential power of the dispossessed.

“For now, it suffices to say that Malcolm’s understanding of solidarity, lived in the midst of social conflict -- with its more realistic appraisal of both the obstacles that justice faces and the power struggle needed to achieve it, is a valuable corrective for an overly optimistic Catholic perspective.”

So what was Malcolm X’s “realistic appraisal”? The judgment is harsh.

Malcolm X, whom Massingale described as “one of the most influential articulators of the African-American experience in the latter part of the 20th century,” essentially dismissed Christianity as a failed, white man’s religion.

At the base of this, according to Malcolm X, was Christianity’s failure to combat racism, a failure he said was tied into to its religious symbol structure, especially its image of a white God. Malcolm X argued that the representation of the divine in Western Christianity served not merely or solely to provide a “sacred canopy” for racial injustice and white supremacy. It also served to bolster the internal sense of superiority of whites -- both American and European -- and the inferiority of black and other nonwhite peoples.

In Malcolm X’s words, this involved “a dual brainwashing, rendering whites unaware of the horrors of racial oppression and black people passive in its wake.”

Massingale said that found in Malcolm X’s critique of religion is the uncomfortable, and thus deeply resisted, truth of how Christianity has served as a rationalization of vested interests. Malcolm’s discourse, he said, strips away the facile belief that our church has in the compatibility of Christian belief with the praxis of social justice.

Clearly, this idea demands further reflection and it is an important one, deserving of the attention of Catholic theologians and the wider church.

Building on this thought, Massingale spoke of the sense of abandonment, betrayal and psychological wounding found in the works of Malcolm X, who articulated the voice of many voiceless people.

These realities led Malcolm X to lash out, opening him to the possibility of being dismissed in the halls of academia. Dismissing him, however, would be to overlook an important voice, said Massingale, who concluded that the deeper significance of Malcolm X’s critique is that it represents an interrogation and rejection of the cultural symbol system of Western Christianity.

Said Massingale: “He advances an understanding that racism is a cultural reality, a culture of racially conferred white dominance. ... He thus implicitly argues that effective antiracist action must address these deep cultural roots -- with the attendant threat to white identity -- rather than focus upon racism’s more obvious yet relatively superficial external manifestations as injustice.”

At a recent U.S. bishops’ meeting on cultural diversity in the church, it was revealed that white Anglos (those whom the Census Bureau identifies as “white non-Hispanics”) are no longer the majority of the U.S. church. We are now a faith community with no single majority racial group.

Gearing off of Massingale’s insights, the questions that need to be answered are these: Can our faith community more openly share with each other our culturally patterned racial prejudices and insights, and by so doing, strengthen our faith bonds? And, if we find the means, can we lead by example and even act as healers in what could be some tumultuous days ahead?

Stories in this series

|