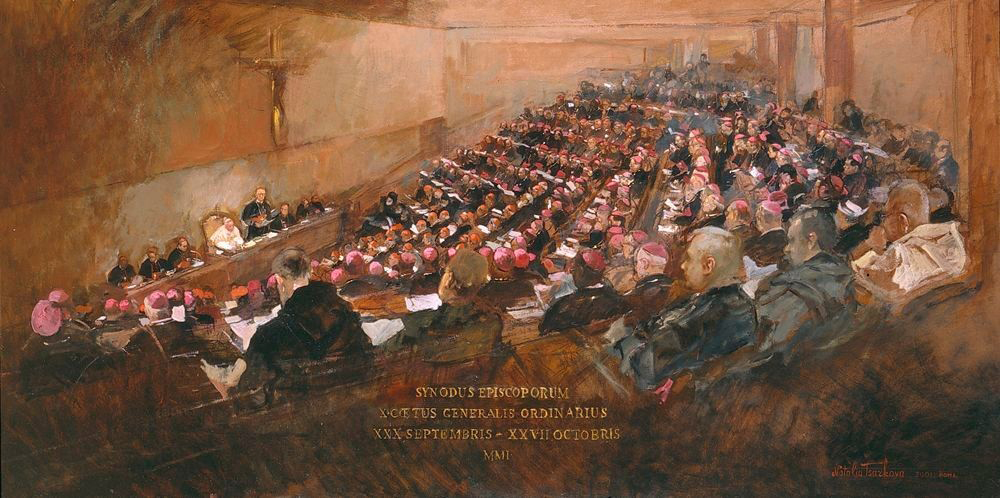

A painting of bishops in the synod hall (Courtesy of the Vatican)

On Sept. 30, 464 people will gather in Rome to pray at the start of an unusual undertaking, the Synod on Synodality. Then, for the three days leading up to the actual meeting, they will be in a spiritual retreat. After that, the talking will begin.

What will they talk about? That is the big question. Catholics who have heard about the synod are wondering what is happening. It is not supposed to be that way.

In October of 2021, every Catholic — in fact, every interested party, Catholic or not — was supposed to be invited to enter what is known as a "discernment process" to think, pray and talk about how the church can move forward. Rome sent general instructions with the idea that small groups would gather to consider what the church should be doing and how to do it better.

Transparency was supposed to be uppermost, though some American parishes held invitation-only meetings and did not provide summaries of their proceedings to their parishioners or even to the individuals they had invited to their meetings. Similarly, several U.S. dioceses have kept their reports secret, or published only summaries.

Advertisement

By August 2022, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops joined 111 other national bishops' conferences in sending Rome a 10-page summary of U.S. diocesan reports.

The next round of prayer and discernment, held in spring 2023, focused on the Document for the Continental Stage, a global summary created from the 112 national reports. Seven continental assemblies — North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, Oceania, Europe, Asia, Africa and Madagascar, and the Middle East — met and provided responses.

Six of the continental assemblies managed to convene their members in person, often across large territories and different time zones. The exception was the North America (U.S. and Canada) assembly, which met by Zoom, prompting critics to point out that avoiding in-person meetings, which take longer and are more difficult to organize, defeats the entire synodal process.

Then, in June 2023, the "Instrumentum Laboris," or working document, a synthesis of the continental responses, appeared.

Now, as people from around the world head to Rome, U.S. Catholics often remain disconnected from the event and the proceedings. There is still no widespread understanding of what synodality is or how it is supposed to work. Several dioceses seem to have moved on, emphasizing the July 2024 Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis.

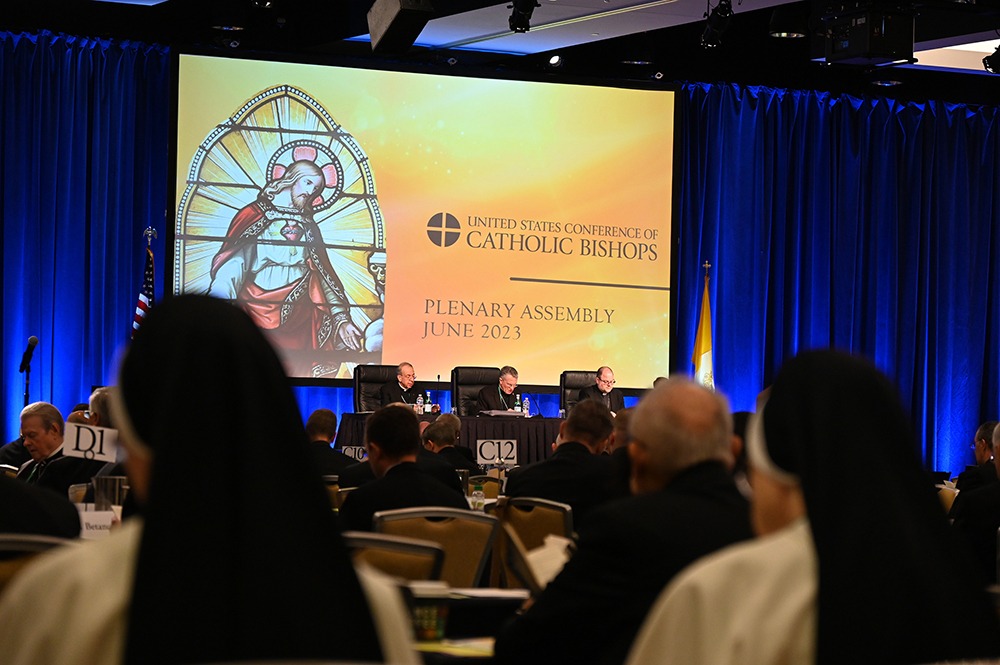

The U.S. bishops' conference demonstrated its lack of interest at its meeting in June. Its appointed synod manager, Bishop Daniel Flores of Brownsville, Texas, initially was not scheduled to speak. When media pointed this out, he was added to the schedule and gave perhaps the most eloquent presentation of the entire meeting. But first, Archbishop (soon to be Cardinal) Christophe Pierre, the papal nuncio to the U.S., gave the assembly a good talking-to. Pierre plainly told the assembled bishops that synodality was real, Catholic and here to stay.

That is where things are right now.

Two nuns, foreground, attend the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops meeting in Orlando, Florida, June 15. (RNS/Jack Jenkins)

A significant number of U.S. bishops have dug their heels into a "pray, pay and obey" model of church, whereas Pope Francis is trying to move it to a cooperative effort in which all members play a part.

A significant number of U.S. bishops have dug their heels into a "pray, pay and obey" model of church, whereas Pope Francis is trying to move it to a cooperative effort in which all members play a part. The recalcitrant bishops seem only to want Francis' papacy to end and do not care whether that's by retirement or by death. They disagree with the concept that every Catholic has the right to speak, to question, to discern the ways in which the church can move forward.

Some bishops are enthusiastically behind the synod, others are having nothing to do with it. They may misunderstand the synod's restrictions. Doctrine is not up for change. That means everything from teachings on the resurrection of Christ to restrictions against gay marriage are not under consideration. What it does mean is that discontinued practices, such as ordaining married men as priests and women as deacons, can be considered.

The considerations will be done in a quiet and prayerful atmosphere over four weeks punctuated by half days of prayer. Except for Masses and a few speeches, the proceedings will not be televised. Further, journalists will not be permitted in the Paul VI Hall, where the synod participants, including more than 50 women, will convene. There will be media briefings, but this first session of the two-part synod (another is scheduled for October 2024) is meant to be a prayerful gathering where participants can share their thoughts and ideas freely.

At the end, the Vatican will publish a synthesis document. And it will all begin again at local levels. One can only hope that more people in the U.S. will get to participate.