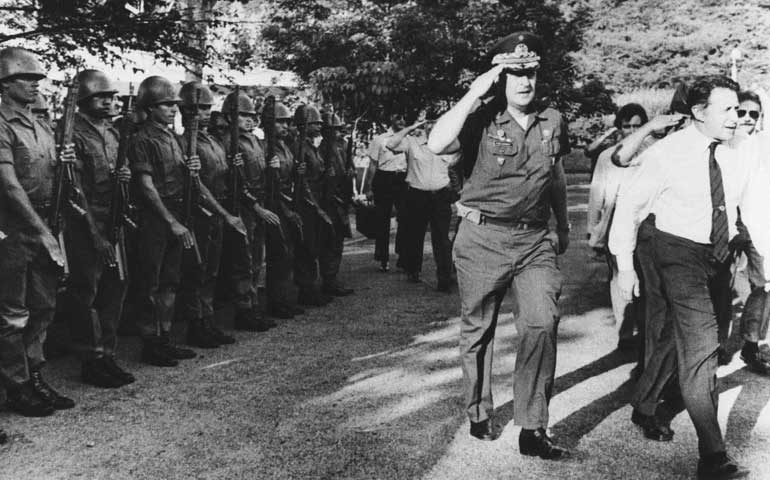

U.S. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger, right, walks with Gen. Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova in front of Salvadoran troops in San Juan Opica, El Salvador, on Sept. 7, 1983. (AP Photo/Romero)

Update: The New York Times has reported that former Salvadoran defense minister Gen. Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova was deported Wednesday. Vides Casanova landed at the international airport in Comalapa, El Salvador, just after 12:30 p.m., one of dozens of Salvadoran deportees aboard an Immigration and Customs Enforcement charter flight, the Times reported, citing a Salvadoran immigration official.

A former Salvadoran defense minister who's been living in Florida for 25 years is a step closer to deportation after the highest U.S. immigration appeals court found he covered up torture and murder by his troops, including the 1980 murders of four U.S. churchwomen by members of the National Guard.

The March 11 ruling by the Board of Immigration Appeals upheld a deportation order against Gen. Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova, head of the National Guard from 1979 to 1983 and Minister of Defense from 1983 to 1989.

The board also upheld the principle of "command responsibility," saying that "he participated in the commission of particular acts of torture and extrajudicial killing of civilians" by the fact that they "took place while he was in command." He knew about them but "did not hold the perpetrators accountable," the board said.

That interpretation of a 2004 anti-terrorist law sets a major precedent, since it does not require "direct participation" by a commander, according to Carolyn Patty Blum, senior legal adviser with the Center for Justice and Accountability, which had represented some of the torture victims.

The board's decision on Vides Casanova is significant not only for its use of the concept of "command responsibility," but also for the fact that the general was once a close ally of the United States, and the highest-ranking military commander successfully prosecuted under a provision of the 2004 law.

He was the recipient of two Legion of Merit awards by the Reagan administration and was given safe haven by the Bush administration to live in Florida, where his wife, Lourdes, owned considerable property. His profile was made even higher by his father-in-law, Prudencio Llach Schonenberg, who was a coffee baron and the Salvadoran ambassador to the Vatican during the time Vides Casanova was the most powerful man in the military.

In the case of the churchwomen, the board relied, in part, on the 1993 U.N. Truth Commission report. That report concluded that Vides Casanova "knew that members of the National Guard had committed the murders" of Maryknoll Srs. Ita Ford and Maura Clarke, Ursuline Sr. Dorothy Kazel, and lay missionary Jean Donovan, but he "made no serious effort to conduct a thorough investigation."

The board wrote that Vides Casanova "knowingly shielded subordinates from the consequences of their acts and promoted a culture of tolerance for human rights abuses."

In cases involving two Salvadorans, Dr. Juan Romagoza and Daniel Alvarado, the court found that Vides Casanova knew of their torture but took no action against the torturers. In fact, he promoted the major who oversaw the torture of Alvarado.

In 1980, Romagoza was "beaten, shocked with electrical probes all over his body, sexually assaulted with a stick and hung from the ceiling for several days," according to the board's summary of his testimony.

Alvarado was falsely accused of killing a U.S. military adviser and signed a confession after seven days of torture. He was held for another two years after U.S. officials told Vides Casanova they were torturing the wrong man. The Swedish government finally obtained his release.

In its decision, the board discarded Vides Casanova's argument that he should not be deported because he was "consistently and uniformly led to believe" that his actions were consistent with official U.S. policy.

As evidence, the defense cited his Legion of Merit awards and the fact that the U.S. never cut off economic aid to El Salvador during the time he was in power, aid that amounted to $1 million a day.

"While the Court does not conclude that all of [Vides Casanova's] actions were consistent with U.S. policy," the board wrote, "the declassified government documents in the record certainly establish that American officials were generally informed of [his] actions with regard to human rights abuses in El Salvador."

However, it stated that the 2004 anti-terrorist statute "does not make allowances for motives," so the court "must find that any discussion regarding why [Vides Casanova] may have assisted or otherwise participated in extrajudicial killings or torture is not relevant."

The court proceedings largely depict U.S. officials trying to rein in the general, and don't begin to reflect the full extent of the U.S. role. It mentions nothing, for example, about the training of thousands of Salvadoran officers at the U.S. Army's School of the Americas when Vides Casanova was in power.

Manuals used at the school and disseminated throughout Latin America through U.S. Army Mobile Training Teams advocated torture and assassination -- among the crimes for which Vides Casanova is cited.

The school's Counter Intelligence manual targeted priests and nuns: "The terrorists tend to be atheists, devoted to violence. This does not mean that all terrorists are atheists. In Latin America's case, the Catholic priests and the nuns have carried out active roles in the terrorist operations."

El Salvador was one of the school's top clients in the 1980s. Three of the five officers cited by the U.N. Truth Commission in connection with the churchwomen's murders were trained at the school.

Furthermore, the United States sent Vides Casanova and the Salvadoran high command double messages -- that human rights must be respected, and that anything goes in fighting what Washington tried to characterize as a war against communist aggression.

The Carter administration, according to Cornell University historian Walter LaFeber, encouraged the coup that brought Vides Casanova to power. It also sent the clear message that neither the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero of San Salvador nor the murders of the U.S. churchwomen would stop U.S. aid from flowing.

The Reagan administration not only dramatically increased the aid, but helped Vides Casanova downplay the women's murders. Reagan's nominee for U.N. ambassador, Jeane Kirkpatrick, declared immediately after the killings in early December 1980, "I don't think the government [of El Salvador] was responsible. The nuns were not just nuns; the nuns were political activists."

The following month, the U.S. ambassador to El Salvador, Robert White, sent Secretary of State Alexander Haig an angry cable about the State Department telling Congress that the Salvadoran investigation into the women's murders was "proceeding satisfactorily." The claim was "not backed up by any report from this embassy," White said.

White later said Haig fired him after he refused Haig's demand to "use official channels to cover up the Salvadoran military's responsibility for the murders of four American churchwomen."

Haig also publicly maligned the women by suggesting, "Perhaps the vehicle the nuns were riding in may have tried to run through a roadblock, or may have accidentally been perceived to have been doing so, and there may have been an exchange of fire."

Later, the Reagan administration awarded Vides Casanova two Legion of Merit awards despite a 1983 investigation by federal Judge Harold Tyler that concluded Vides Casanova was likely "aware of, and for a time acquiesced in, the cover-up" of the murders.

What's more, the U.S. Army invited Vides Casanova to be a guest speaker at the School of the Americas in 1985. At the time, the school taught the core principles of the Reagan administration's low-intensity-warfare strategy, which advocated any means necessary to achieve political objectives.

In 1989, the Bush administration arranged Vides Casanova's entry into the United States, which had deported hundreds of poor Salvadorans to an unknown fate during the war.

According to White, Vides Casanova's record disqualified him for a U.S. visa, but the Bush administration got around immigration policies under a law dating back to World War II where "the CIA can settle one hundred collaborators a year in the United States, no questions asked," White wrote in 2004.

While Vides Casanova can appeal the board's deportation decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit, the board's ruling is expected to impact pending cases, including the appeal of Gen. José Guillermo García, another ex-Salvadoran defense minister and Legion of Merit recipient.

García, a graduate of the School of the Americas (now known as the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation), also lives in Florida.

Last year, an immigration judge in Miami found that atrocities committed by troops under García's command were also not fully investigated, much less prosecuted.

García, the court said, protected death squads and "assisted or otherwise participated in" torture and assassinations during his tenure as defense minister from October 1979 to April 1983.

Among the atrocities were the murders of Romero, the four U.S. churchwomen and more than 1,000 peasants at El Mozote, the worst massacre of civilians in contemporary Latin American history.

When the two generals arrived in Florida in 1989, U.S. aid was still flowing and the U.S. military training never stopped. Nor did the killing, until the United Nations brokered a peace in 1992.

The U.N. Truth Commission found that 85 percent of the most serious atrocities came at the hands of the military, and 5 percent at the hands of guerrilla organizations. More than 75,000 Salvadorans died before the violence ended.

[Linda Cooper and James Hodge are the authors of Disturbing the Peace: The Story of Father Roy Bourgeois and the Movement to Close the School of the Americas.]