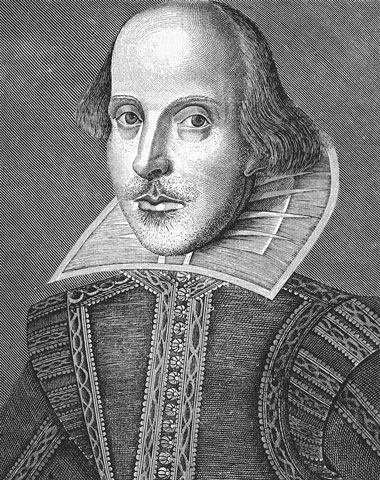

(Newscom/Prisma/Album)

Scholars have probed Shakespeare's plays for centuries, hoping to seize a look into the Bard's soul, to determine if he was a man of faith. The latest academic to take this journey, or at least to write a book about it, is David Kastan, a Yale University English professor who concludes in A Will to Believe: Shakespeare and Religion that the plays are not keys to Shakespeare's own faith, but rather register the ways religion changed his world.

"One thing we know nothing about is what Shakespeare believed," he told an audience of about 130 gathered in early March in Manhattan. "We know lots of what he said. He lived in a culture where religion just saturated the culture. Religion is the way culture expressed its fundamental values for Shakespeare."

The discussion was presented by the Pearl Theatre Company, one of New York's most respected off-Broadway companies, and the Shakespeare Society, whose artistic director, Michael Sexton, moderated the 90-minute onstage talk at the theater.

"It's interesting why scholars have for so long been determined to find out what Shakespeare believed," Kastan said, adding that that quest partly informed his book's title. "It's our will to believe we can know something that intimate about Shakespeare. We can't."

What we do know is that he was a popular playwright who didn't "become Shakespeare as we know him until the 1790s, when he becomes the voice of our shared humanity. He becomes the image of British inventiveness."

This reflected the 18th century's enlightenment and devaluation of religion.

"Critics started to turn Shakespeare into this voice. He becomes our secular Bible."

This assessment of Shakespeare continued through the 19th century, Kastan said, with scholars claiming Shakespeare's greatness was that he didn't get trapped in religion, that he wasn't interested in religious distinctions.

But in the 20th century, especially in the 1990s, scholars began to raise the question of whether Shakespeare was Catholic. They point to an incident in 1592 when Shakespeare's father was fined for not attending church -- weekly Anglican church attendance was required by law -- as proof the family was Catholic. Kastan said it was just as likely he was in debt and didn't want to encounter a creditor.

"I think it's a dumb question," Kastan said. "He had the ability to register the moment. That's what he does well. He engages what it means to be human. Religion was inexplicable."

But it certainly was felt in Shakespeare's time. "They would have smelled the burning flesh of the burned heretics. That was so much a part of his world."

The Reformation had separated Catholics from Anglicans, but Catholics were still there.

"If you were living in the 16th century your grandparents were Catholic," Kastan said. "There were powerful pockets of Catholics. If nothing intensified the difference, it was not a problem. As long as it didn't become public."

He summed it up with a line from "Measure for Measure": "Grace is grace despite of all controversy."

"When you think about the plays, he's interested in the things of this world. This isn't Dante. He doesn't have that kind of piety, devotion."

Kastan said another reason people have speculated that Shakespeare was Catholic is because he created friars in several plays, but those plays were set in Italy.

"What's the option? The Catholicism is not so much consciously pro-Catholic as neutral," Kastan said.

Even plays that seem now to be about religion were not necessarily viewed that way by Shakespeare's audiences. The depictions of Judaism and Christianity in "The Merchant of Venice" strike us differently in our post-World War II viewings than they would have in Shakespeare's day, when the play would have been seen as a romantic comedy, Kastan said.

"It sets up religion as a term," he said. "To me, it's how much alike everyone is. Christian generosity turns out to be hardly generous. It exposes the values of Venice."

In Elizabethan England, nobody wanted to look too deeply into religion, he said. But people could put their belief in the theater, the art of it, just as they do now.

"What happens in the theater is the audience is always having to engage its belief," he said. "You allow yourself to forget these are four people living in Manhattan. They become these beings. We as an audience are exerting our will to believe."

[Retta Blaney is an award-winning journalist and author of Working on the Inside: The Spiritual Life Through the Eyes of Actors.]