I spent much of this week in San Antonio for the spring meeting of the U.S. bishops, where the press gallery was the loneliest corner of the room. Largely because the bishops opted not to put the flap over Notre Dame and President Barack Obama on their public agenda, many media organizations, including every major secular news outlet in the country, took a pass.

In reality, the fact that the Notre Dame-Obama controversy wasn't floated in public merely meant that it was talked about everywhere else.

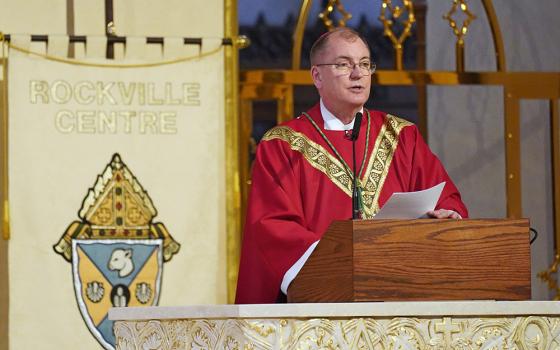

Archbishop George Niederauer of San Francisco said on Wednesday that it came up "at breakfast, over coffee and in the hallways," and several bishops reported that the topic surfaced during their private regional meetings Wednesday morning. Bishops also reported that it came up in Thursday afternoon's closed-door executive session, in the form of a discussion of the conference's 2004 policy statement on engaging figures in political life. (That statement stipulated that Catholic institutions should not honor politicians who hold views contrary to church teaching, a provision that many bishops felt Notre Dame violated.) The session was led by Bishop William Murphy of Rockville Center, chair of the bishops' committee on Domestic Justice and Human Development, which is responsible for the document.

I tried to take the bishops' temperature on the Notre Dame controversy, and I came away with four basic impressions about where things stand, and where they might go from here.

The bishops (surprise!) don't all think alike

One question left hanging in the air from the controversy has been what to make of all the bishops who didn't speak out. To be sure, the number of bishops who came out against the university was extraordinary. The web site Lifesitenews.com came up with a total of 83, far in excess of the number of bishops who normally take up other hot-button issues, such as communion bans for pro-choice politicians.

Still, there are a total of 425 bishops in the United States, including 258 who are active as diocesan bishops or auxiliaries. So, how should one interpret the silence of the more than 300 prelates who held their tongues?

One thing my time in San Antonio made clear is that at least some of those 300-plus bishops were not entirely on the side of the critics.

"I'm sure the enemies of the church were delighted to see the bishops attacking the country's premier Catholic university, but I wasn't delighted," one bishop told me. He said he was "appalled" by the criticism from some of his brother bishops.

Another prelate pulled me aside to ask why Obama's Catholic critics didn't give him credit for pledging at Notre Dame to respect a "conscience clause," meaning legal protection for health care workers who object to providing abortion services. Yet another bishop said he's concerned that the approach of some of his colleagues vis-à-vis Obama risks becoming "too negative, too narrow, and too partisan."

I have no way of knowing to what extent such views represent a larger body of opinion among the bishops, but I can at least confirm they exist.

Of course, this isn't exactly a shocker. In a group of more than 400 headstrong leaders, there's likely to be more than one view on most matters. Yet it never fails to confound some people that there are different currents within the conference, perhaps because it makes it more difficult to engage in lazy generalizations about what "the bishops" think.

Sources said that when the bishops got into executive session, some argued that matters such as the Notre Dame affair should be left in the hands of the local bishop, without a scrum of prelates from other parts of the country piling on. Others complained that when some bishops speak up on an issue and others don't, it allows activist groups to cast various bishops as either heroes or villains. Still others suggested that the conference needs to consider questions of enforcement when Catholic institutions don't heed directions from the bishops.

When I asked Curry the day before if he felt the bishops were likely to reach a decision in the executive session, he laughed.

"It would be wonderful if we could have a decision that everyone would agree on," he said, "but I doubt very much that everybody is going to come to a consensus at the moment."

Why didn't the moderates speak out?

An obvious question begged by the foregoing is why bishops one might describe as "moderate" on the Notre Dame/Obama controversy weren't willing to speak publicly.

To some extent, the answer is that it always works this way. On virtually every issue in the church, it's easier to find sharply defined voices on either side than in the middle. Moderates believe in collegiality, so they're hesitant to be seen as criticizing brother bishops. Further, the whole point of being a moderate is to see oneself as a mediator of conflict, not a party to it. When self-described moderates see a fight brewing, their instinct is to not to take sides, but to explain why both have a point.

In the case of the Notre Dame controversy, I suspect two other factors were also in play.

First, Notre Dame didn't just invite Obama to give a speech, but they also awarded him an honorary doctorate. Many bishops saw that as out of step with their 2004 statement, "Catholics in Political Life," which included the language cited above about withholding honors from politicians whose views conflict with church teaching. (The extent to which its provisions apply to Obama has been debated, since he's not Catholic. Most bishops presume, however, that when it's a question of a moral truth, the principle applies to non-Catholics as well.)

Some bishops said privately that had it not been for the honorary doctorate, they wouldn't have objected to seeing Obama speak at Notre Dame; after all, they say, he's the President of the United States, and the church is obligated to deal with him. In the abstract, some might have been inclined to see the invitation favorably even with the honorary doctorate, but they felt duty-bound to respect a collegially enacted policy of the conference.

Second, many bishops regard it as a matter of principle that any response to a local dispute, even one with national implications, ought to come from the local bishop, who in this case was Bishop John D'Arcy of Fort Wayne-South Bend. Once D'Arcy had expressed his opposition to the Obama event, many bishops would have felt uncomfortable taking a different position, whatever their private views.

During their executive session on Thursday afternoon, there was discussion about issuing a statement of support for D'Arcy, who also made a presentation to the body.

Compounding this point was the impression that D'Arcy, now 76 and on the brink of retirement, was not adequately consulted by Notre Dame. Since D'Arcy is a widely respected figure, not to mention someone perceived to have gone to great lengths over the years to defend the university, this impression was another reason why some bishops might have hesitated to say anything that could be perceived as unsupportive of him.

One cardinal laughingly put the impact of it all on D'Arcy this way: "That was one hell of a retirement present!"

A paradox for the center-left

Using political categories to evaluate the church is always sloppy, but at a rough-and-ready level, sometimes it can help make sense of things. Applying that framework to American Catholicism, one might say that the "center-left" in the States has long favored a strong bishops' conference, often accusing the Vatican and/or conservative American bishops of undercutting the authority of the conference.

During the 1980s, hard-hitting documents from the U.S. conference on the economy and on nuclear war were celebrated by progressive-minded Catholics. Still today, center-left Catholics generally expect strong leadership from the conference on their core concerns, including immigration reform, the death penalty, and opposition to conflicts such as the U.S.-led war in Iraq. If it's not forthcoming in a given case, center-left Catholics often rue the "decline" of the conference.

Yet there's a growing tendency today among moderate-to-progressive Catholics to argue for allowing certain matters to be resolved by individual bishop, rather than seeking a binding national policy. That was the position taken by the center-left during debate over implementation of Ex Corde Ecclesiae, John Paul's document on Catholic higher education, and it's the same position increasingly taken in liturgical disputes. Famously, the commission led by Cardinal Theodore McCarrick regarding communion bans for pro-choice politicians ended up recommending that the decision be left to the local bishop, an outcome hailed by many on the center-left and blasted by many on the center-right.

On the direct question raised by the Notre Dame controversy -- whether the bishops need a stronger policy governing speakers at Catholic universities -- the dynamics seem likely to play out the same way, with moderate-to-progressives arguing for local flexibility, and conservatives clamoring for a tough national stance.

Obviously, a partial explanation for all this is easy to spot: As the conference has become less likely to adopt positions congenial to the center-left, those Catholics have become less eager for bold leadership from the conference.

So here's the paradox. On the one hand, the center-left can't hold onto an expectation of strong national leadership only on the issues it likes, which may imply gradually declining expectations of the conference. As enthusiasm for the conference in that camp diminishes, however, so too may commitment to it, suggesting that the historical tendency of center-left bishops to win elections and to hold key positions in the USCCB may abate -- which could clear the way for the center-right to adopt precisely the strong positions that at least some on the center-left might fear.

The $64,000 question for the center-left camp is whether those bishops can figure out a way to argue for local flexibility, while at the same time maintaining a strong investment in the conference. To say the least, it will be interesting to see how that paradox is resolved.

From bishop-as-ruler to bishop-as-teacher

Despite the popular mythology that Catholicism is rigidly centralized, the Notre Dame/Obama affair offered a classic reminder of the limits of episcopal power. In this case, the combined force of 83 bishops -- including the bishop of the local diocese, the president of the national bishops' conference, and five cardinals -- wasn't even enough to compel a Catholic university to find another commencement speaker.

Like many Catholic universities in America, Notre Dame is sponsored by a religious order and governed by an independent board of directors (consistent with the famous 1967 Land O'Lakes statement), which means that bishops have few direct ways to impose their will. Further, the decade-long battle over Ex Corde illustrated that casting the relationship principally in terms of power is usually a losing proposition, regardless of the eventual outcome.

Going forward, some bishops may want to cast about for new ways of forcing places like Notre Dame to toe the line. One wonders, however, if that's the right lesson to draw. The way the Obama controversy played out could plausibly support another conclusion: In the absence of power, to fall back on persuasion. (Whether the bishops were actually persuasive is, for purposes of the theory, beside the point.)

I ran this hypothesis past Archbishop Timothy Dolan of New York on Thursday, who was among the 83 bishops who criticized Notre Dame for the Obama invitation. In broad strokes, he seemed to agree.

"As far as authority and power go, it may look like a defeat. But in terms of a recovery of episcopal voice and muscle, it may have succeeded," Dolan said.

"I always look at things as a church historian," Dolan said. "Twenty-five years from now, when somebody's doing a master's thesis on all of this, it could be a chapter where the bishops came together and said, 'This is a moment when we need to exercise some teaching authority.' "

"We kitchen-tabled an issue," Dolan continued. "In normal Catholic homes throughout the country, people are talking about this. Granted, there might not be unanimity, but there's recognition that the bishops have something to say, they need to say it, and they ought to say it."

In truth, not every Catholic home in America may concur that those 83 bishops needed to say what they did. The discussion in Thursday's executive session would seem to suggest that even some bishops aren't inclined to look at the Notre Dame affair as a shining moment in the recent exercise of the teaching office.

Yet Dolan's reply nonetheless points to a possible paradigm shift: Circumstances may be compelling bishops to become more comfortable exercising their authority in the academy through the bully pulpit, through public teaching (and even, to some extent, through public "shaming"), rather than edicts.

If the model of bishop-as-teacher is indeed gaining strength, it's a potentially fascinating transition -- ironically, one for which many leaders in Catholic higher education have long clamored. Some may not like what the bishops had to say, but having said it may help the bishops to be less inclined to engage in battles over power, and more willing to embrace the art of argument.

Over the long run, who knows where that might lead?

Read John's daily reports from the bishops' meeting on the NCR blog, NCR Today.