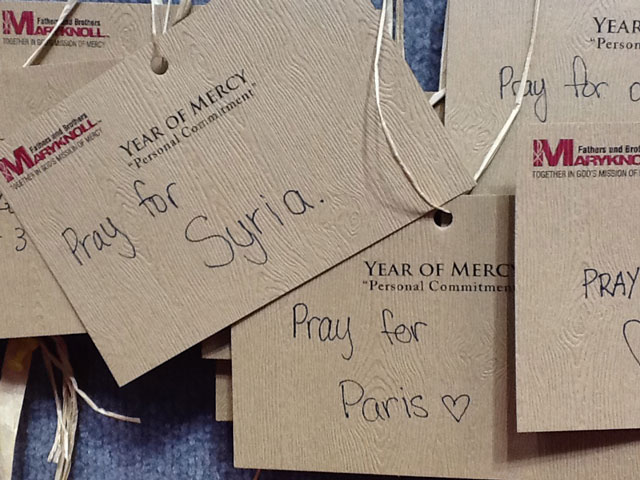

Visitors add their mercy prayer cards to the booth of the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers at the National Catholic Youth Conference in Indianapolis in November 2015. (Photos courtesy of Greg Darr)

"Hey, there's something funny about your map."

I fielded remarks like that time and again from teens who visited our Maryknoll booth at the National Catholic Youth Conference (NCYC) in Indianapolis. Most of them noticed it right away: "It's upside down!"

"Well, technically not," I explained. "This is what the Earth looks like when you see it from a different position in space. It's as real as the perspective you're used to, with the north on top and the south at the bottom. Look at it this way for a while and see if it does anything to your assumptions about what's important."

We had mounted the map just as the cartographer designed it. All the sizes of the countries were relatively the same. The difference was in perspective or, in cartographic jargon, its projection. This map -- a Hobo-Dyer Equal Area Projection -- was oriented so that Europe and North America appeared at the bottom and at the corners. Looking at the world upside down challenged the young people to see countries from a new, unfamiliar perspective and perceive their relationship to other parts of the world in a fresh way.

Our map wasn't the only unusual thing there. For the uninitiated, NCYC is a biennial Mardi Gras of teenage Catholicism. More than 20,000 youth and their adult chaperones, youth ministers and bishops occupied downtown Indianapolis for a few days this past November to get to know each other and deepen their faith. In some dioceses, every teen must have been rounded up from fast food hangouts, put on a bus and sent on a multihour road trip, only to be deposited among their equally bleary-eyed and caffeinated comrades scooped up from soccer practice elsewhere.

The results, however, were comic, manic and amazingly Catholic. Packs of youth and their chaperones wandered the convention hall where our Maryknoll mission booth was located. Some wore cheesesteak hats; others cow costumes. Most were in some kind of garb representative of their dioceses or parishes. They ran, congealed, flirted and prayed. And they lined up nearby to greet bishops like rock stars -- an out-of-body experience for many of our diocesan leaders, I imagine.

For those of us a generation or two older, this teen-spirit spectacle was also a little disorienting. We, too, were compelled to see a few things from a new, unfamiliar perspective. In our Maryknoll case, much of it had to do with mercy.

At the outset of the church's "Jubilee Year of Mercy," we invited youth who visited our booth to write brief prayers, thoughts or commitments related to mercy. We then hung them around our "upside-down" map. As we did so, we explained that Pope Francis encourages us all to look at the peoples of our world from a new perspective -- not from fear, suspicion or hatred but instead through eyes of love, compassion and mercy.

The youth astounded us in their response -- they used all the cards we brought. It was clear that they had something to say.

Aside from a sprinkling of hashtags, the cards adorning our map could've been authored for the most part by any recent generation. Many were prayers for the hungry and hurting, the poor and persecuted. A lot had to do with family and other loved ones. Many expressed a yearning for a deeper prayer life, to be more just or compassionate. A remarkable number of teens are concerned for souls in purgatory. Others, for world peace.

An unsurprising number of cards linked prayer and mercy to recent events in Paris and Syria. Some were so specific that, for example, if a boy named Quinten ever came around to our booth, he would've known that someone wants him to "stay out of trouble."

What struck me from these cards and mostly from youth with whom I spoke was not that their sense of mercy is much different than my generation's. It's that their sense of perspective about the world, even in light of their Catholic faith, seemed somehow different, even without the upside-down map. Still, I couldn't quite put my finger on it.

After I returned from NCYC, I visited a dear friend -- a devout Catholic -- and told her of my experiences there. Of her own grandchildren she remarked, "Sometimes, I just don't understand them. They go to church, are active in their youth groups, even pray the rosary. But then they tell me that gays and lesbians should be allowed to marry. It's like they've turned everything I hold dear about the family upside down."

That evening, I was scrolling through my Facebook feed and paused upon a nearly blank image. Twenty-five years earlier, in 1990, Voyager 1 turned its camera upon our solar system and took a planetary family portrait. Obscured in the sun's rays and almost entirely unnoticeable in the endless expanse of space is a pale blue dot smaller than a pixel -- Earth. From that perspective, it's impossible to know what's up or down. What strikes the eye and soul is Earth's breathtakingly tiny footprint in the vastness of existence.

Then it hit me: Perhaps this is the image of our world that our youth were born to see. Perhaps it's from this perspective, unlike those of earlier generations, that our youth are called to witness Christ. It's a perspective that's a bit new and unfamiliar to those of us who matured with Earth-centric and ethnocentric worldviews.

Today's youth take for granted an image of the world so small in the vastness of space that it's impossible to tell at times what's up or down. Maybe, for many youth, it doesn't really matter. It's the vastness that counts -- the infinite expanse of God's mercy in which our world strains and turns.

I came away from the expanse of an Indianapolis convention center and its thousands of youth with my own perspective changed. Yes, there was something funny going on -- it was taking place in my heart. It happened when groups of teenagers wearing disco-inspired accessories pointed at an upside-down map, struggled to find exotic sounding countries and, in the end, left their mark with words of mercy.

Theirs is a faith big enough for cow costumes and Communion. And, in its breadth of acceptance, big enough for me.

[Greg Darr is a returned Maryknoll lay missioner having served in Kenya. He is currently a vocation minister with the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers. All of the Soul Seeing columns are available at NCRonline.org/blogs/soul-seeing.]