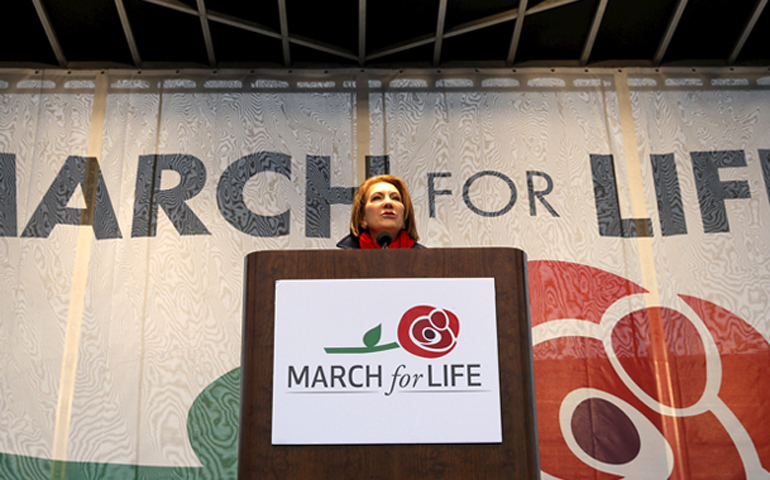

Republican presidential candidate Carly Fiorina speaks at the National March for Life rally in Washington on Jan. 22, 2016. (Reuters/Gary Cameron)

My friend, a high school teacher in the Washington, D.C., area, invited me to speak to his pro-life club in advance of the March for Life last week. When I asked what I might expect from the audience, he dropped this bomb:

"Well, you know the president of the club? She’s an atheist."

I looked at him for a few seconds, momentarily taken aback.

But I should have known better. Yes, the pro-life movement in the U.S. began as a movement of religious people. But today it is very diverse, with groups like "Secular Pro-Life" giving a very public and influential home for nontheists in the movement.

The annual March for Life has become a gathering of people from every race, language and way of life. Among the marchers this year were liberals, Jews, pagans, blacks, Latinos, and gays and lesbians. As has been the case for some years now, the crowd was also disproportionately young -- connecting to the myriad of interesting events [and the tens of thousands of people] through the March for Life app.

The new energy of the pro-life movement comes in part from a growing consensus on abortion in the United States.

Though an overwhelming majority of Americans (including 3 in 4 who identify as pro-life) want to see abortion legally available in cases of rape and the endangered life of the mother, multiple polls have found that a clear majority (including 1 in 4 who identify as pro-choice) want it legally restricted in other circumstances.

If you go by development of the fetus instead of circumstances of pregnancy, there is also a strong consensus found in multiple polls. About 6 in 10 want to see abortion largely available before 12 weeks, while about 7 in 10 want to see it largely restricted after 12 weeks.

Unfortunately, this consensus is not reflected in most of our public discussions of abortion. These tend to be dominated by extremist positions.

I document many of the reasons for this in my book “Beyond the Abortion Wars,” including the media’s interest in framing the issue has an “us vs. them” fight to the death between those who want abortion banned and those who want it available.

But one issue I overlooked was the significant impact of presidential primary campaigns, especially as candidates’ hopes for the nomination push them to satisfy extremist wings in their party.

Take Marco Rubio. Seen in this election cycle as an alternative to people such as Donald Trump and Ted Cruz, he has nevertheless been forced by the extreme pro-life groups to draw focus away from the American consensus on more abortion restrictions and onto his views on abortion in the case of sexual violence.

If he is the nominee, he will now be forced to defend his wildly unpopular view that abortion ought to be restricted even in this horrific circumstance, a view rejected even by a majority of those who identify as pro-life.

Hillary Clinton once thought that abortion should be rare, but in her current presidential run she has been pushed by extreme pro-choice groups to adopt the “abortion as a social good” model. No more talk of reasonable restrictions. Indeed, she now even argues that taxpayers should be forced to pay for abortions, another wildly unpopular proposition, rejected by a majority of those who identify as pro-choice.

It often takes many years for national politics to catch up with a growing consensus, especially on contentious issues. In 2004, for instance, GOP strategists put same-sex marriage bans on the ballot in several states in an attempt to drive up voter turnout among their base. By 2012, however, that strategy seemed nearly incomprehensible given the broad public support for gays and lesbians to marry.

Something similar is going on with abortion today. Our public discourse, political debates and cultural imagination are trapped in the “us vs. them,” “choice vs. life,” “woman vs. baby” antagonistic narrative from the 1980s. But the growing American consensus on abortion is more complex and, frankly, much more interesting.

Americans want abortion to be far more restricted than it is now. Given our support for women, Americans want abortion to be legal in certain limited circumstances. This consensus is an important and happy development, and it is long past time that gatekeepers of our public discussions change their language and assumptions to reflect it.

Evaluating the positions of the presidential candidates would be a good place to start.

[Charles C. Camosy is associate professor of theological and social ethics at Fordham University.]