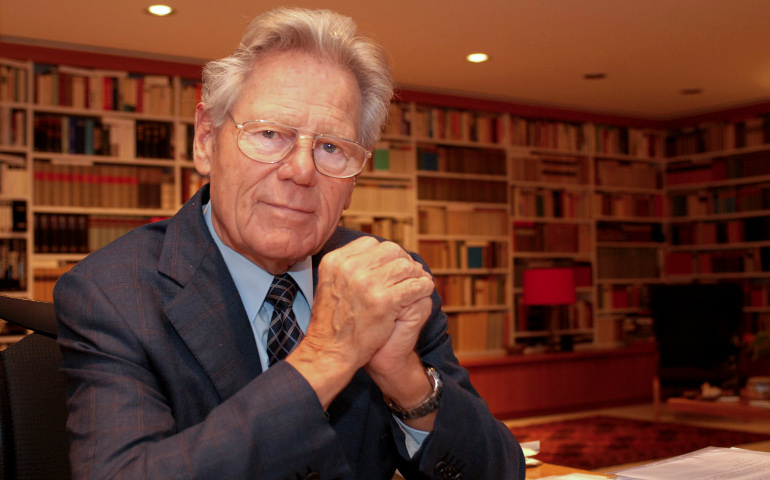

Theologian Fr. Hans Küng is pictured in his office in Tubingen, Germany, in this February 2008 file photo. (CNS/KNA/Harald Oppitz)

Next week, Hans Küng, the Catholic priest and Swiss theologian, will mark his 88th birthday. The fifth volume of his complete works, titled Infallibility, has just become available from the German publishing house Herder. In connection with the release of Infallibility, Küng has written the following “urgent appeal to Pope Francis to permit an open and impartial discussion on infallibility of pope and bishops.” The text of his urgent appeal is being released simultaneously by National Catholic Reporter and The Tablet.

It is hardly conceivable that Pope Francis would strive to define papal infallibility as Pius IX did with all the means at hand, whether good or less good, in the 19th century. It is also inconceivable that Francis would be interested in infallibly defining Marian dogmas as Pius XII did. It would, however, be far easier to imagine Pope Francis smilingly telling students, “Io non sono infallibile” — “I am not infallible” — as Pope John XXIII did in his time. When he saw how surprised the students were, John added, “I am only infallible when I speak ex cathedra, but that is something I will never do.”

I became acquainted with the subject very early in my life. Here are a few important historical dates as I personally experienced them and have faithfully documented in Volume 5 of my complete works:

1950: On Nov. 1, facing huge crowds in St. Peter’s Square and supported by numerous high church and political dignitaries, Pope Pius XII definitively proclaimed the Assumption of Mary as a dogma. “The immaculate Mother of God, the ever Virgin Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory.” I was there in St. Peter’s Square at the time and must admit that I enthusiastically hailed the pope’s declaration.

That was the first infallible ex cathedra proclamation by the church’s senior shepherd and highest teaching authority, who had invoked the special support of the Holy Spirit, all according to the definition of papal infallibility laid down at the First Vatican Council of 1870. And it was to remain the last ex cathedra proclamation to date, as even John Paul II, who restored papal centralism and was always happy to seek publicity, did not dare to play to the gallery by proclaiming a new dogma. As it was, the 1950 dogma proclamation had been made despite protests from the Protestant and Orthodox churches and from many Catholics, who simply could not find any evidence in the Bible for this “truth of faith revealed by God.”

I remember German theology students, who were our guests in the Collegium Germanicum (German College) in Rome, discussing the problems they had with the dogma in the refectory at the time. Only a few weeks previously, an article by the then leading German patrologist, Professor Berthold Althaner, a highly regarded Catholic specialist in the theology of the Church Fathers, had been published in which Althaner, listing many examples, had shown that this dogma had did not even have a historical basis in the first centuries of the early church. It goes back to a legend in an apocryphal writing from the fifth century that is brimful of miracles.

We seminarians at the German College at the time thought that the students’ “rationalist” university teachers had kept the Pontifical Gregorian University’s general perception regarding this dogma from them. The general perception at the Gregorian was that the Assumption dogma had “developed” slowly and, as it were, “organically” in the course of dogma history, but that it was already ascertained in Bible passages such as “Hail (Mary) full of grace (blessed art thou),” “the Lord is with you” (Luke 1:28), and although not “explicitly” expressed, it was nevertheless “implicitly” incorporated.

1958: Pius XII’s death marked the end of a century of excessive Marian cults by the Pius popes that had begun with the definition of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception in 1854. Pius XII’s successor, John XXIII, was disinclined toward new dogmas. At the Second Vatican Council, in a crucial vote, the majority of the council fathers rejected a special Marian decree and in fact cautioned against exaggerated Marian piety.

1965: Chapter III of the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church is devoted to the hierarchy but, oddly enough, Paragraph 25, which is on infallibility, in no way actually goes into it. What is all the more surprising is that in actual fact the Second Vatican Council took a fatal step. Without giving reasons, it expressly extended infallibility, which was confined to the pope alone at the First Vatican Council, to the episcopacy. The council attributed infallibility not only to the assembled episcopacy at an ecumenical council (magisterium extraordinarium), but from then on also to the world episcopacy (magisterium ordinarium), that is, to bishops all over the world if they were agreed and decreed that a church teaching on faith or morals should permanently become mandatory.

1968: the year the encyclical Humanae Vitae on birth control was published. That the encyclical was released on July 25 of all times, which was not only during the summer holidays but, on top of that, in the middle of the Czechoslovak people’s fight for freedom, is generally interpreted as Roman tactics so that there would be less opposition to it. Perhaps, however, it was quite simply because work on this sensitive document had only just been finished. Whatever the reason for the timing, the encyclical hit the world “like a bomb.” The pope had obviously greatly underestimated the resistance to this teaching. Isolated as he was in the Vatican, he had not envisaged that the world public would react quite so negatively.

The encyclical Humanae Vitae, which not only forbade as grave sins the pill and all mechanical means of contraception but also the withdrawal method to avoid pregnancy, was universally regarded as an incredible challenge. Invoking the infallibility of papal, respectively episcopal teaching, the pope pitted himself against the entire civilized world. This alarmed me as a Catholic theologian. I had by then been professor of theology at the Catholic theological faculty of Tübingen University for eight years. Of course, formal protests and substantive objections were important, but had the time not now come to examine this claim to the infallibility of papal teaching in principle? I was convinced that theology — or, to be more precise, critical fundamental theological research — was called for. In 1970, I put the subject up for discussion in my book Infallible?: An Inquiry. I could not have foreseen at the time that this book and with it the problem of infallibility would crucially affect my personal destiny and would present theology and the church with key challenges. In the 1970s, my life and my work were more than ever intertwined with theology and the church.

1979-80: the withdrawal of my license to teach. In Volume 2 of my memoirs, Disputed Truth, I have described in detail how this was a secret campaign carried out with military precision, which has proved to be theologically unfounded and politically counterproductive. At the time, the debate about the withdrawal of my missio canonica and infallibility continued for a long time. It proved impossible to harm my standing with believers, however, and as I had prophesied, the controversies regarding large-scale church reform have not ceased. On the contrary, during the pontificates of John Paul II and Benedict XVI they increased on a massive scale. That was when I went into the necessity of promoting understanding between the different denominations, of mutual recognition of church offices and celebrating the Lord’s Supper, the question of divorce, of women’s ordination, mandatory celibacy and the catastrophic lack of priests, but above all of the leadership of the Catholic church. My question was: “Where are you leading this church of ours?”

These questions are as relevant today as they were then. The decisive reason for this incapacity for reform at all levels is still the doctrine of infallibility of church teaching, which has bequeathed a long winter on our Catholic church. Like John XXIII, Francis is doing his utmost to blow fresh wind into the church today and is meeting with massive opposition as at the last episcopal synod in October 2015. But, make no mistake, without a constructive “re-vision” of the infallibility dogma, real renewal will hardly be possible.

What is all the more astonishing is that the discussion (of infallibility) has disappeared from the scene. Many Catholic theologians have no longer critically examined the infallibility ideology for fear of ominous sanctions as in my case, and the hierarchy tries as far as possible to avoid the subject, which is unpopular in the church and in society. When he was prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Joseph Ratzinger only expressly referred to it very few times. Despite the fact that it was left unsaid, the taboo of infallibility has blocked all reforms since the Second Vatican Council that would have required revising previous dogmatic definitions. That not only applies to the encyclical Humanae Vitae against contraception, but also to the sacraments and monopolized “authentic” church teaching, to the relationship between the ordained priesthood and the priesthood of all the faithful. And it applies likewise to a synodal church structure and the claim to absolute papal power, the relationship to other denominations and religions, and to the secular world in general. That is why the following question is more urgent than ever: Where is the church — which is still fixated on the infallibility dogma — heading at the beginning of the third millennium? The anti-modernist epoch that rang in the First Vatican Council has ended.

2016: I am in my 88th year and I may say that I have spared no effort to collect the relevant texts, order them factually and chronologically according to the various phases of the altercation and elucidate them by putting them in a biographical context for Volume 5 of my complete works. With this book in my hand, I would now like to repeat an appeal to the pope that I repeatedly made in vain several times during the decadelong theological and church-political altercation. I beg of Pope Francis — who has always replied to me in a brotherly manner:

“Receive this comprehensive documentation and allow a free, unprejudiced and open-ended discussion in our church of the all the unresolved and suppressed questions connected with the infallibility dogma. In this way, the problematic Vatican heritage of the past 150 years could be come to terms with honestly and adjusted in accordance with holy Scripture and ecumenical tradition. It is not a case of trivial relativism that undermines the ethical foundation of church and society. But it is also not about an unmerciful, mind-numbing dogmatism, which swears by the letter, prevents thorough renewal of the church’s life and teaching, and obstructs serious progress in ecumenism. It is certainly not the case of me personally wanting to be right. The well-being of the church and of ecumenism is at stake.

“I am very well aware of the fact that my appeal to you, who ‘lives among wolves,’ as a good Vatican connoisseur recently remarked, may possibly not be opportune. In your Christmas address of Dec. 21, 2015, however, confronted with curial ailments and even scandals, you confirmed your will for reform: ‘It seems necessary to state what has been — and ever shall be — the object of sincere reflection and decisive provisions. The reform will move forward with determination, clarity and firm resolve, since Ecclesia semper reformanda.’

“I would not like to raise the hopes of many in our church unrealistically. The question of infallibility cannot be solved overnight in our church. Fortunately, you (Pope Francis) are almost 10 years younger than I am and will hopefully survive me. You will, moreover, surely understand that as a theologian at the end of his days, buoyed by deep affection for you and your pastoral work, I wanted to convey this request to you in time for a free and serious discussion of infallibility that is well-substantiated in the volume at hand: non in destructionem, sed in aedificationem ecclesiae, ‘not in order to destroy but to build up the church.’ For me personally, this would be the fulfillment of a hope I have never given up.”

[Fr. Hans Küng, Swiss citizen, is professor emeritus of ecumenical theology at Tübingen University in Germany. He is the honorary president of the Global Ethic Foundation (www.weltethos.org). The sixth volume of his complete works, Church Reform, is expected later this year also from Herder. This article was translated from the German by Christa Pongratz-Lippitt.]