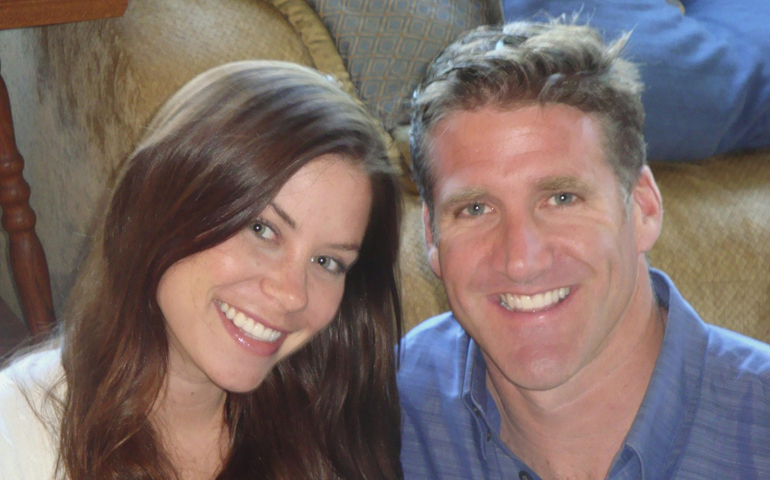

Brittany Maynard and her husband, Dan Diaz (CNS/Reuters)

When Brittany Maynard became the youthful face of the right-to-die movement, she brought to the public table several fierce debates.

Some people wouldn't call Maynard's death a "suicide" because, overwhelmingly, the people who commit suicide are people who have a choice to continue to live. People with a terminal diagnosis -- like Maynard's aggressive brain tumor that was robbing her of the life she said she very much wanted to live -- don't have that choice.

So is she the public face of "suicide"? Many would find the term "physician-assisted dying" more accurate.

Like the word "suicide," "suffering" is another word that is used -- and valued -- very differently. By dying at age 29, Maynard signaled that carrying on while she no longer knew herself was pointless and would only prolong the agony of those who loved her.

She saw no value in suffering.

That may be one reason the right-to-die movement, led by advocacy groups such as Compassion & Choices and others, is so worrisome to many of its opponents. If suffering is optional, then it might also be spiritually meaningless.

That's a very different perspective than what is taught by many of the world's religions and philosophies.

Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, in his first Easter address to the world after his 2005 election, spoke of heroic suffering, which he said should be accepted by believers to unite them with Jesus' suffering for the love and salvation of mankind.

The world had just witnessed his predecessor, St. John Paul II, grapple with his own public suffering as a series of end-of-life ailments robbed the once-vigorous pope of his vitality.

But there was little doubt in John Paul's mind about the value of suffering. "Your sufferings, accepted and borne with unshakeable faith, when joined to those of Christ take on extraordinary value for the life of the Church and the good of humanity," he said in his 1993 address to mark the First Annual World Day of the Sick.

Yet in Oregon, Washington, Vermont, Montana and New Mexico, terminally ill patients who fear "intolerable suffering" can ask a doctor for assistance -- a prescription for a lethal drug they alone can take -- in dying on a day when they believe they have "suffered enough."

But what's "enough?" Is there a just-right amount?

"Suffering" has no qualitative measure. Unlike physical pain -- expressed with a grimace or a moan or a rational rating of 1 to 10 for the doctor making rounds -- suffering is psychological; it's emotional. It's fear, despair, anger for the life past or present, or the unknown to come.

Suffering may be born of relationships with other people or with God, relationships gone sour, sad or hollow. As San Francisco rabbi and former hospice chaplain Michael Goldberg said: "A great deal of the suffering at the end of life is either self-inflicted or inflicted by friends and relatives. It's not due to disease."

And often, it's not the sick person who suffers.

"Psychic suffering requires consciousness. If you are deeply comatose, you don't feel pain," said medical anthropologist Sharon Kaufman, who spent years in three hospitals observing death, dying and decision-making for her book, ... And A Time to Die: How American Hospitals Shape the End of Life.

Since suffering, like beauty, is in the mind of the beholder, the choice to bear it, numb it or dumb it down is personal, cultural and spiritual.

Maynard told CNN: "I considered passing away in hospice care at my San Francisco Bay-area home. But even with palliative medication, I could develop potentially morphine-resistant pain and suffer personality changes and verbal, cognitive and motor loss of virtually any kind."

In Iowa, a high school student with an aggressive brain tumor has battled through treatments and surgeries to potentially add years to her life. According to The Des Moines Register's coverage of Bethany Gruich, 17, she whispered to her mother in one of the worst days that she was not ready to die. Maynard's choice was unacceptable to this Baptist family. Bethany's mother, Lori, said, "My faith goes against that on all levels."

Catholic doctrine excludes physician-assisted dying when suffering appears endless and overwhelming.

"When can we say that the potential to grow or overcome or bear that suffering, that potential which made that suffering meaningful, is gone forever?" asks Jesuit Fr. Kevin FitzGerald, of the Center for Clinical Bioethics at Georgetown University. The Jesuit priest's questions are rhetorical. He asks: "Why do we think someone is enlightened enough to know their suffering is not redemptive?"

Traditional Islam, like Judaism and Christianity, sees life as God's gift to give and to take away.

But for the Hindu or Buddhist, suffering may be accepted as inescapable.

"The law of karma says that every embodied soul, every living person, depending on the kind of life one has led, will reap the consequences of our actions. Injustices, and suffering in this world might only be explained by the past," said Varadaraja V. Raman, an associate editor of the Encyclopedia of Hinduism.

Maynard may represent a disconnection from views rooted in religion or karma. To her, suffering borne by her body and her loved ones' emotions were not worthwhile if she were no longer living, thinking, acting as herself.

Her choice to die may reinforce to many -- particularly religiously disengaged young millennials -- that spiritual meaning, like suffering, is up to you.

"When my suffering becomes too great, I can say to all those I love, 'I love you; come be by my side, and come say goodbye as I pass into whatever's next,' " she told CNN. "I will die upstairs in my bedroom with my husband, mother, stepfather and best friend by my side and pass peacefully. I can't imagine trying to rob anyone else of that choice."