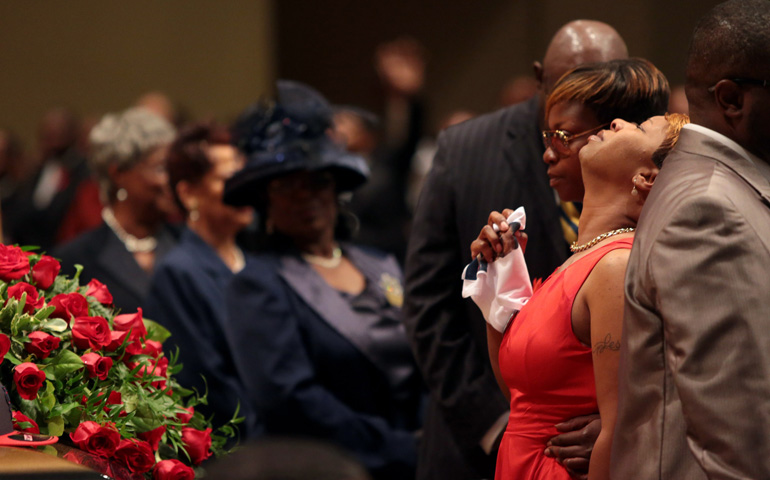

Lesley McSpadden is comforted during the Aug. 25 funeral service for her son, Michael Brown, inside Friendly Temple Missionary Baptist Church in St. Louis. (CNS/EPA/Robert Cohen, pool)

Mourners, public officials and celebrities entered Friendly Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Ferguson, Mo., site of Michael Brown's funeral Aug. 25, with arms raised in the posture of surrender.

"Hands Up, Don't Shoot" has become the slogan of protest for the Aug. 9 killing of the unarmed young black man who reportedly had his hands up when he was shot six times by Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson.

Marches, protests and town hall meetings followed. Participants by the thousands came from Ferguson, its surrounding greater St. Louis region and elsewhere. A few were spoiling for a fight; many others were shaken from their lethargy by ominous rumblings from the racial fault line that runs through this notoriously segregated metropolitan area -- people who, like myself, had pushed the seemingly intractable problems of race to the back burner of their moral agenda.

I attended no marches or meetings, and I told myself I had no time to watch the funeral either, on what was to be a tightly scheduled day. But toward the end of the morning news shows, there it was. For the next three hours, I was riveted.

At the end of the service, I switched off the TV and turned my attention to what had transfixed me though all those eulogies and prayers.

It was, I realized, rising hope.

In the days that followed, I went to YouTube to watch the eulogies again and again with family and friends.

There was Calvina Brown, Michael Brown's stepmother, reporting that her stepson, "Mike Mike," had prophesied his death, saying shortly before he was killed, "One day the whole world will know my name."

There was Charles Ewing, Brown's uncle, overcome with emotion as he declared, "There is a cry coming from the ground" -- a cry for vengeance and justice "for Michael Brown, for Trayvon Martin, for the children in the Sandy Hook Elementary School, the Columbine massacre, for black-on-black crime."

There was the Rev. Al Sharpton, wrapping it up with a double-edged sermon well worth catching belatedly, regardless of personal opinions of the man. He was at once the civil rights activist excoriating a militarized police force for devaluing black Americans with over-policing, and the stern elder statesman calling his own people to account for devaluing themselves.

"We have to be outraged by our disrespect for each other; our disregard for each other; our killing and shooting and running around gun-toting each other," he charged. "Some of us act like the definition of blackness is how low you can go. ... Blackness was: No matter how low we was pushed down, we rose up anyhow. ... And now we get to the 21st century; we get to where we got some positions of power. And you decide it ain't black no more to be successful."

After the funeral, protests became fewer and calmer, and I found myself confronting inner chaos as I tried to put a finger on the source of my hope.

Was it based on a desire for return to normalcy and an end to my nagging conscience? Was it based on the grand jury's work, aimed at unraveling the many conflicting accounts of events leading to Brown's tragic death?

Neither seemed likely to bring resolution, let alone justice.

What about Sharpton's pointed words to the black community? After years of repressed guilt -- for white privilege, for doing too little to effect change, for the grief that assaults me day after day as I hear yet another report of a black youth's death by another black youth's hand -- was I now being let off the hook?

No, the surge of hope I felt contained no sense of relief. I wanted to do more, not less -- but like many others, from a different starting point. Its source, I realized, was the possibility that these ominous rumblings, bringing national and international attention to my city, just might herald a new chapter in our nation's painful, halting journey toward integration and equality.

Here is what one local leader had to say: The Rev. Susan Sneed, Methodist pastor and organizer of Metropolitan Congregations United in St. Louis, told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that Brown's death had brought issues to the forefront that could no longer be ignored.

"Now I think people know, one bad traffic stop, and it could be my neighborhood," she said. "I think people want things to get back to normal, but it's going to be a brand new normal."

Other voices, new to me, emerged: Solomon Alexander, African-American blogger in St. Louis whose compelling piece on white fear was published in the Post-Dispatch Aug. 22. Kevin Powell, New York-based black activist and author who co-founded BK Nation, led a town hall meeting at the Missouri History Museum Aug. 25, where he urged youth to lead the fight against every form of oppression -- racism, sexism, classism and homophobia.

As I saw commitments like these arising from around the area and nation, I realized that I too want to be part of the solution and that I am far from alone.

I am no authority on race relations. My experiences with black Americans are decidedly mixed. On one hand are the many delightful working relationships with black colleagues over a long career. On the other are at least 15 crimes in St. Louis that have touched me personally: an uncle, a special friend (a Catholic nun) and two colleagues murdered; another colleague and an acquaintance shot and left for dead; at least nine relatives, friends and colleagues raped or robbed at gunpoint. All of the victims were white; all but one of the perpetrators were black.

With the exception of having indirectly experienced so many crimes, I am the average middle-class American when it comes to black-white issues -- concerned, but detached. What do I have to offer?

And that fleeting dodge became my "aha" moment.

We need everyone, men and women of all races -- average citizens and known leaders -- to stand together as we address the problems that most of us could recite in our sleep: underemployment, broken communities, failing schools, drugs, apathy, crime, black and white fear.

One known black leader, Daniel Isom, retired St. Louis police chief and recently appointed the new director of the Missouri Department of Public Safety, served on a panel at an NPR-sponsored meeting Aug. 28 titled "Ferguson and Beyond: A Community Conversation."

"I'm looking in the mirror ... to see what I can do better at holding myself accountable. ... But I'm gonna tell you, I can't do it by myself," Isom said. "It has to be a collective group pushing for change."

We will need patience. Not everything we ask or say will be welcome. I will be curious to know, for instance, what a black parent means when accusing a white teacher of trying to make a black child into a white one when the teacher explains what the black child needs to do to succeed. Friends who teach have reported such challenges to me several times.

How do the black parent's standards differ, I would want to know. What is it that parent wants for his or her child?

And, no doubt, blacks seeking change will have many unwelcome challenges for me.

Pastor Willis Johnson, whose Wellspring Church in Ferguson was the site of "Ferguson and Beyond," closed the meeting with these words: "We've got a long struggle ahead of us. We've got great work to do. I am hurt ... and sometimes I feel a little helpless. But I am hopeful because I know there's a better day."

Maybe that's the modern-day equivalent of "I have a dream." Maybe it's all we get. So let's run with it -- those experienced in race relations, those who are not.

Let's make sure that, for all the right reasons, Michael Brown's name is indeed remembered by the world.

[Pamela Schaeffer is a former religion editor at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and a former writer and editor at NCR. She has lived most of her life in St. Louis.]