More than 60,000 people gather to celebrate the beatification of Capuchin friar Fr. Solanus Casey at Ford Field in Detroit Nov. 18. (William E. Odell)

On Nov. 18, a cold and relentlessly rainy Saturday here, the Catholic Church beatified Fr. Solanus Casey, Detroit's most beloved and famous Capuchin friar, moving him a big step closer to canonization.

Casey, who died in 1957 at 86, was a Wisconsin native, the son of Irish immigrants. Because of struggles in Capuchin seminary classes taught almost exclusively in German, he'd been ordained a "simplex priest" in 1904. That meant he was denied the priestly faculties of preaching homilies and hearing confessions. Consequently, priestly assignments meant mostly simple jobs: serving as the monastery doorkeeper, training altar boys, moderating the Ladies Altar Society.

Nonetheless, in New York, Detroit and in Huntington, Indiana, where he served, people found a readiness to listen and a deep faith in the priest who answered the door. They also found that when Casey prayed for their intentions, prayers were answered with amazing frequency. As the years went by, healings were reported, dangerous surgeries averted, alienated people mysteriously reconciled.

By his beatification, six decades after his death, it was clear that many Solanus stories from the 1930s, '40s and '50s had never dimmed or died. Detroit, which had unofficially "canonized" him during his lifetime, remembered his unflagging support for the Detroit Tigers, his love of hot dogs with onions, his sense of humor, his devotion to his large Irish family.

In addition, the Motor City never forgot that during the Depression when the city's automobile factories closed, Casey helped to start the Capuchin's soup kitchen to feed the hungry. The kitchen is still operating today.

Planning the large beatification event at Ford Field in Detroit was daunting, admitted Capuchin spokesmen Fr. Larry Webber and Br. Richard Merling.

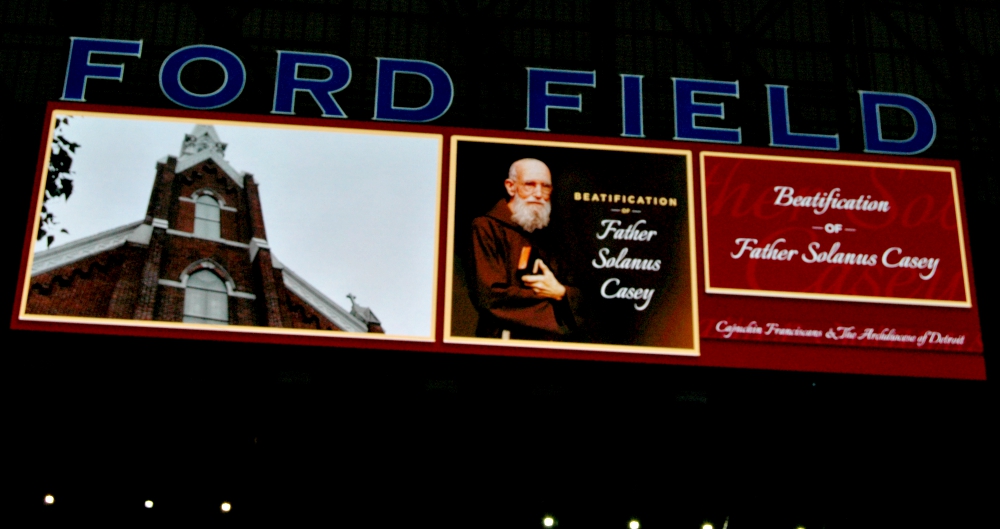

Hung high above Ford Field's end zones, electronic banners celebrate the beatification of Fr. Solanus Casey 60 years after his death. (William E. Odell)

These two Capuchins, vice-postulators of the cause for canonization, explained that a steering committee of lay and religious leaders with a variety of competencies had worked with Detroit Archbishop Allen Vigneron for months.

"It was literally bigger than the Super Bowl," admitted Webber. But, he added, "things moved in a way that God wanted and I trusted in that. In the end, I prayed that the celebration could really be a moment of grace for the people of God and an inspiration for their faith."

As the eucharistic liturgy and rite of beatification was about to begin at 4 p.m., thousands of ticketed pilgrims poured into a domed stadium that had become a church overnight. Large banners celebrating Casey's beatification hung high above the end zones. At midfield, on a large raised stage, a cherry-wood altar designed and built for St. John Paul II's visit to Detroit in 1987 was in place.

The beatification rite preceded the liturgy for which Cardinal Angelo Amato, prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints and papal delegate, was the presider. After Vigneron read a formal request for beatification, an apostolic letter from Pope Francis was read.

Then Amato held up the decree declaring that Venerable Fr. Solanus Casey would now be known as "Blessed Solanus Casey." Applause rocked the stadium where, on any other day, the only heroes are those who score touchdowns or field goals.

Paula Medina Zarate is escorted by two Franciscans as she carries a relic of Blessed Solanus Casey during his beatification Mass Nov. 18 at Ford Field in Detroit. (CNS/Courtesy of Michigan Catholic/Jeff Kowalsky)

Before Mass began, Paula Medina Zarate of Panama carried a wooden reliquary holding relics of the new beatus to a table in front of a large portrait of Solanus. It was Zarate's miraculous healing from a congenital and incurable skin disease in 2012 that was accepted for Casey's beatification in September of 2016.

Zarate, 58, when she was healed, was a religion teacher and catechist in Panama. She visited Casey's tomb in Detroit to pray for others but soon sensed that she should also pray for herself. She did and within hours, the scaly skin disease, ichthyosis vulgaris, was gone.

In his homily, Amato spoke about the unique humility, selflessness and heroic charity of Casey, who is the second American-born male to be beatified this fall. Fr. Stanley Rother, a missionary martyred in Guatemala in 1981 was beatified in Oklahoma Sept. 23.

Casey's "profound faith allowed him to reach out to others as a brother, independently of their race or religion," the cardinal told the massive congregation.

The testimony of a black Capuchin friar who knew Solanus in the 1950s is "meaningful," Amato said, quoting the friar: "I am the first black member of the Capuchin order in the United States. ... He saw all people as human beings, images of God. ... He did not pay attention to race, color or religious creed."

The trust and faith that Casey had in the providence of God was also remarkable, according to Amato.

One day during the Great Depression, after he helped to create the soup kitchen for the poor, Amato said, those in the kitchen discovered that there was no more bread.

"More than 200 people [were] waiting for something to eat. Father Solanus began to recite the Our Father," he explained. "A little bit later, a knocking was heard at the door and the baker walked in with a large basket full of bread. ... When the people saw this, they began to cry with emotion. Father Solanus simply stated, 'See? God provides.' "

Cardinal Angelo Amato, prefect of the Congregation for Saints' Causes, concelebrates the beatification Mass of Blessed Solanus Casey Nov. 18 at Ford Field in Detroit. (CNS/Courtesy of Michigan Catholic/Jeff Kowalsky)

The story about Casey praying the Our Father for bread was familiar to most — if not all — of those sitting in two large "special guest" sections directly in front of the altar and flanked by sections of Capuchins. Ranging in age from 5 months to some in their 80s were 340 members of the extended Casey family. About 15 were Casey relatives from Ireland. The others, like Toby Joyce and his family, came from around the United States and were descendants of Fr. Solanus Casey's 11 brothers and sisters who married and had families.

"My grandmother was the granddaughter of Margaret Casey who was a sister of Father Solanus," Joyce said. "So, Solanus is my great-great-great uncle. It's three greats!"

It was a challenge, he said, when talking with others in the Casey clan to see how they were all connected.

Joyce and his wife and their three children had come from Prineville, Oregon, for the beatification event.

Katie and Toby Joyce pose with their children — Taylor, 12, Tanner, 10, and 7-year-old Brendan Solanus Joyce -- before the Nov. 18 Mass and beatification rite for Fr. Solanus Casey at Detroit's Ford Field. (William E. Odell)

"The stories my grandmother always told about Father Solanus meant so much to me and my siblings," he said after the event. "We wanted to bring our children to be part of this. We gave the name Solanus to our third child. He is Brendan Solanus Joyce. We wanted all of our children to understand the great things that this man did. All of our kids got to sit at Father Solanus' oak desk where he used to meet and talk with people."

One of the most moving moments for him, Joyce recalled, took place even before the beatification and Mass began.

"I saw the people getting off buses and flocking in. How many lives he touched! It was amazing that this one person of faith could impact so many people and he's been gone for 60 years. The stories have been passed down."

Vigneron, sharing some reflections about the man beatified in his diocese, said Solanus Casey's spiritual impact is remarkable and bound to grow.

Advertisement

"More and more, I have come to think that Father Solanus is kind of a living image and icon that helps us to think of Pope Francis' [2013 apostolic exhortation] 'Joy of the Gospel,' " Vigneron suggested. "The Holy Father tells us that we need to share the Gospel of mercy with those who are on the periphery. Father Solanus did that with people from two parts of that periphery — those who were materially poor and those who were suffering from illness or problems in the family."

"I've heard people say," Vigneron concluded, "that Father Solanus would be a little embarrassed by all of this notoriety. But I don't really think so. He would know that it was about giving glory to God and he would have a lot of joy in that."

[Catherine M. Odell is a regular contributor to NCR.]