(Unsplash/Daniel McCullough)

Editor's note: According to a 2008 Pew Research study, one of 10 U.S. adults is a former Catholic. Some have moved on to other denominations, others have no church affiliation at all, still others have formed their own communities of former Catholics. In this five-part series, former NCR editor Tom Roberts examines the choices many former Catholics have made as they decided to move away from the institutional church.

Martha Ligas learned about the Community of St. Peter in Cleveland six months before she ventured into a worship service. She hesitated because she did not want to step over an invisible line that she had straddled for so long, one foot in and one foot out of the Roman Catholic Church.

For this young but lifelong Catholic, a product of Catholic schooling from elementary through Loyola University Chicago and an advanced degree in ministry at Boston College, leaving the institutional structure was a difficult decision.

"Catholic is just how I see the world," she said. "I knew nothing else than Catholic."

The Community of St. Peter is an independent community, not affiliated with the Cleveland Diocese, that self-describes as Catholic, eucharistic, and "preserving and renewing a living tradition." It formed in April 2010 when a significant portion of St. Peter's Parish refused to disperse to other parishes after Bishop Richard Lennon closed it as part of a diocesan-wide downsizing.

The Community of St. Peter is representative of one expression that has emerged amid the vast Catholic diaspora in the United States.

(NCR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Ligas, 32, is part of that large, if not precisely describable, sea of Catholics who have left the institution but retained a connection, often highly personalized and in new forms, to the tradition.

Some communities in the far-flung diaspora seem to be practically dealing with questions and thorny issues previously prohibited from being raised in institutional settings but now integral to the synodal process underway as a result of the Francis papacy.

In Portugal, Pope Francis may have been expressing the feeling of many of those who belong to modern independent eucharistic communities (often referred to as IECs) when he told the gathering at World Youth Day: "There is room for everyone in the church and, whenever there is not, then, please, we must make room, including for those who make mistakes, who fall or struggle."

He continued, "The Lord does not point a finger, but opens wide his arms: Jesus showed us this on the cross. He does not close the door, but invites us to enter; he does not keep us at a distance, but welcomes us."

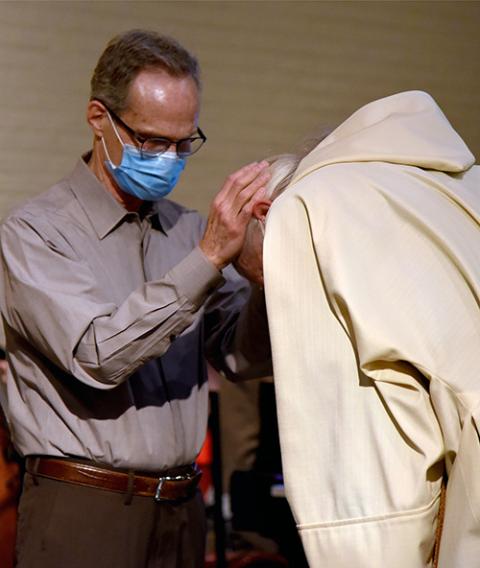

A reconciliation service at the Community of St. Peter in Cleveland during Lent 2022 (Peggy Turbett)

Inclusion without qualification is a familiar theme in independent eucharistic communities, especially when it comes to women, the LGBTQ community, and the divorced and remarried. Social justice themes, outreach to those on society's margins, are also prominent, far more likely to be prioritized on websites than doctrinal or devotional elements of communal life.

No simple or single reason explains why people leave the institutional church. Nor is it easy to characterize groups that claim Catholic identity either historically or those formed more recently outside the institutional boundaries as parishes closed or when a bishop or new pastor decided to upend all that was in place.

Once upon a time we labeled them "fallen away," "lapsed," "ex" or worse. They were Catholics who had left the fold for any number of reasons. Once upon a time, they also were rare enough to stand out, often embarrassed enough to try to keep the leaving quiet. They were branded people.

Not any longer.

Former Catholics are everywhere. There are millions of them. According to a 2008 Pew Research study, one in 10 U.S. adults at the time was a former Catholic. In real numbers, that amounted to 28.8 million former Catholics. Taken as a single entity, they would make up the second-largest denomination in the country after Catholics.

Some of the drop-off has to do with generational differences and a steady decrease in formal religious affiliation, according to a 2021 Gallup Poll.

While the aggregate numbers tell a broad story, the Catholic diaspora, in differing degrees detached from institutional Roman Catholicism, is a diverse and complex reality. Not a few of its manifestations take shape in communities that claim the name Catholic, as well as deep roots in that tradition.

Portraits of Pope Benedict XVI and Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, founder of the traditionalist Society of St. Pius X, flank a crucifix at St. Michael the Archangel Chapel in Farmingville, New York, in this 2009 photo. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

One website lists more than 300 independent eucharistic Catholic communities in 41 states plus the District of Columbia. Not all of them are liberal groups. Some, such as the Society of St. Pius X and the Mount St. Michael community of Spokane, Washington, are ultraconservative. NCR has not attempted to verify the existence of all of them on the list. At the same time, it is clear the list is not exhaustive.

The diaspora would also include the various branches of Roman Catholic Women Priests, as well as a broad network of communities led by ordained women.

An uncertain future

The renowned Czech theologian and philosopher Msgr. Tomas Halik posits a dark time ahead for the church if "it fails to impress a profound transformation not only on ecclesial structures, but on the existential and spiritual dimension of faith," according to a review of his book The Afternoon of Christianity: Courage to Change.

The review, by Jesuit Fr. José Frazão Correia, describes the current moment as a "prophetic warning," for the global church, a "drama constituted by the loss of people, relevance and credibility." It is a moment, on the other hand, that holds the potential for "true spiritual conversion and profound ecclesial reform."

Quoting Halik, Frazão writes, "a real renewal of the Church cannot come from the desks of bishops or from meetings and conferences of experts, but presupposes strong spiritual impulses, deep theological reflection and the courage to experiment."

One might reasonably view the changes underway today, as focused in the synodality effort, as deriving both from bishops at their desks as well as strong spiritual impulses — a kind of permission from the very top, Pope Francis, for experimentation and challenge from the ground up.

If setting the church right, as Halik puts it, requires "courage to experiment," the Catholic diaspora in the United States might have something to offer. Independent eucharistic communities have been experimenting for a long time.

Cover of The Other Catholics: Remaking America's Largest Religion by Julie Byrne (Courtesy of Columbia University Press)

In The Other Catholics: Remaking America's Largest Religion, a study of independent Catholics in the United States, Julie Byrne describes such communities as "Catholicism's research lab." They serve as a lens through which "one can see better the thoughts and unthinkables, centers and peripheries, flows and fault lines of Catholicism and American religion."

She said she "found that independent Catholicism is deeply continuous with the family of Catholicism, linked to many other American faiths, and crucial if we want to understand Catholicism and American religion as a whole."

In her research, Byrne spent a decade following the Catholic Apostolic Church of Antioch. Sounds ancient, and the church on its website makes a specific claim to apostolic succession dating to 1566 and Cardinal Scipione Rebiba. But the church, considered among the first of the American "independents," dates to 1959. Its structure, as is the case with many independent eucharistic communities, is highly democratic and includes women priests and bishops.

In the introduction to her book, Byrne wonders if "maybe independents function for modern Catholicism in the same way as religious orders functioned for late medieval and early modern Catholicisms."

She cites sociologists Roger Finke and Patricia Wittberg as advancing the idea that "religious orders incubate new ideas, serving Catholicism like denominationalism serves Protestantism, but with the advantage of remaining within the fold." In a similar way, perhaps, modern independents test out new ideas while not forming new denominations.

Defining Catholic IECs

In 2009, 230 people from 17 states and the District of Columbia representing 42 self-described intentional eucharistic communities gathered at what was then the 4-H Center in Chevy Chase, Maryland, to discuss their future.

It was the third such meeting that had been organized, largely by the Catholic sociologist William D'Antonio. The first had occurred in 1991 in Washington, D.C.

At the Chevy Chase meeting, literature produced by the organizers described intentional eucharistic communities as "those small faith communities, rooted in Catholic tradition, which gather to celebrate Eucharist on a regular basis. Through sharing liturgical life and mutual support for one another, members are strengthened to live Gospel-centered lives characterized by spiritual growth and social commitment."

One of the discussions prominent during the proceedings was whether, and to what degree, independent communities should retain an attachment to the institutional church.

(NCR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Some, angry over one or another issue, wanted nothing more to do with the institutional church. Others described arrangements where the community met separately but still belonged to a parish and had liturgies celebrated by a priest.

Still others described meeting sometimes on Catholic properties and chapels, sometimes in rented spaces, and celebrating Eucharist with priests who said Mass clandestinely.

D'Antonio, then a fellow at the Life Cycle Institute at the Catholic University of America, viewed intentional eucharistic communities as agents of change. While believing that such communities should retain some connection to the institutional church, he cited such influences on parishes as the priest shortage and demographic shifts, saying, "The church needs us as much as we need the church."

Michele Dillon, another sociologist who had worked on research projects with D'Antonio, also spoke at the gathering and noted a seeming paradox: that while a survey of the group showed that 70% said the institutional church was not important to them personally, much of the conversation about and the rationale for their communities emphasized the importance of Vatican II.

Michele Dillon (Courtesy of Michele Dillon)

"Given your immersion in that whole Vatican II model of church, it's a little ironic," she said, "that at the same time you detach from the institutional church."

In a more recent interview via Zoom, Dillon, dean of the College of Liberal Arts at the University of New Hampshire, noted the "very American sense" Catholics in this country have of "It's our church."

"Of course, it's Vatican II and the people of God, but it's a very American sense compared to in Europe, where people walk away, they don't even want advice. They're just so fed up with what goes on in the church that just as we saw in Ireland so precipitously, and we've seen it earlier in Western Europe, they walk away.

"I think it's wonderful, all of this activity," she said, referring to independent eucharistic communities. "But my point as a sociologist would be that the church is theirs even if they disagree with whatever aspect or many aspects. And if they get exhausted from trying to connect with the church at large, whether it's the Vatican or the local church, then in a sense they're delegitimating their own claims as Catholic."

She cited Dignity USA, a group advocating for LGBTQ rights in the church. She has written about the group in her book Catholic Identity: Balancing Reason, Faith, and Power, exploring why groups that have deep disagreement with church teaching choose to stay and fight. She believes such endurance can bring change.

Advertisement

She argues that events like the synod on the family and the current synodal process are providing small "cumulative accretions" of developments in teaching "that ultimately become part of the permanent record of the church." The synod processes, particularly under Pope Francis, she said, acknowledged the complexities of family life and are giving a hearing to questions and concerns that have been voiced by ordinary Catholics for decades.

Crossing the line

When Martha Ligas eventually attended the Community of St. Peter in 2018, she said, "I found myself in tears because I was so moved, because I found a place where the theology of the liturgy intersected so crisply and clearly with my theology. For me, particularly, it was gender-inclusive language both for people and for God."

It was important, too, she said, that she "saw LGBTQ folks, couples, in the community. There were no restrictions on participation or on sacraments or anything of that nature. I realized, OK, I guess this is going to be that other foot outside the institution — that I've crossed the line."

Ligas, who in a recent community newsletter described herself as "not only a female, but a queer female, and not only a queer female but a queer female steeped in a catholic identity with a call to serve," became a pastoral minister of the community in 2021.

Martha Ligas at the Community of St. Peter in Cleveland on Holy Thursday, April 6, 2023 (Peggy Turbett)

In an interview, she recalled the term "radical relationality," which she learned in one of her classes at Boston College. "When you're Catholic that's how you interact with the world — this constant desire — this Trinitarian desire to build community. It resonated with me so deeply and I said, 'That's what I am and that is always what I will be.'

"At the same time, I'm learning so much more about social justice and, truthfully, becoming so disillusioned with some of the ways the Roman Catholic institution leaves big gaps in living out a social justice mission. ... There is a big gap in who's allowed to use their voice, and I think there's a big gap in who is welcome at the Communion table."

Those realizations collided at some point and, she said with a laugh, "I fell in love with Catholicism and I became disillusioned with Roman Catholicism at the exact same time."

Dillon makes the case, echoing the late Fr. Andrew Greeley, that today's Catholics "will be Catholic on their own terms." But she said the tug, whether inside or outside the institution, is to the sacraments and the theological tradition.

Perhaps as illustration of that pull — and one that would be familiar to many involved in independent eucharistic communities — Ligas is teaching theology at Notre Dame College, is working part time for FutureChurch, and is enrolled this semester in a doctor of ministry program at yet another Jesuit institution, Fordham University.

Part 2 of this series shows the long arc of change and institutional diminishment that has been occurring in the Catholic Church in the United States for decades and that has contributed to the growth of the Catholic diaspora.