(Paul Lachine)

In late February, Maltese Auxiliary Bishop Charles Scicluna told Italian journalists, "From now on, no one" -- and when he said "no one" he meant the 117 cardinals coming to Rome for the conclave that would elect Pope Francis -- "will be able to say they know nothing about what goes on regarding clerical sex abuse." Efforts begun by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger and continued by Pope Benedict XVI are "now a fundamental part of the church's response to sex abuse," Scicluna said. "It will be part of the leadership program of whoever is elected in the Sistine Chapel."

Scicluna, of course, is more than an auxiliary bishop from Malta. He was the prosecutor handling sex abuse cases for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith for 10 years until he was made a bishop last year. He, under the leadership of Ratzinger as the doctrinal congregation's prefect, deserves credit for breaking the ecclesial logjam and beginning to move effectively against clergy who had abused children.

As we sort through Benedict's pontificate and his more than three-decades-long legacy at the top of the church hierarchy, it would be wrong to too easily dismiss what Benedict did to protect children from clergy sex abusers. This does not mean his record is blemish-free or that we agree entirely with the processes used by bishops and the Curia to handle cases of abuse brought against clergy. But there can be no doubt that the church and her children would be in a far worse position if Benedict had not taken control of these cases in 2002.

Chicago Cardinal Francis George acknowledged this in interviews he did before the conclave. "Whoever is elected pope ... he obviously has to accept the universal law of the church now, which is zero tolerance for anyone who's ever abused a minor child."

This seems to be a milestone for the church on this issue and a time for people who have long fought for it to be addressed to declare at least a small victory.

Scicluna concluded his interview saying that the "sore spots" in the church today are violations of the sixth and seventh commandments: sins against purity and theft. "We need to go back to the Gospel," he said. "Whoever is elected pope will have to continue Ratzinger's 'purification' work."

Which brings us to Francis and what could be the next phase in the Catholic church's struggle with this issue. Within days of the new pope's election, his record of handling clergy sex abuse as archbishop of Buenos Aires was called into question. Our senior correspondent, John Allen, looked into these allegations during his recent trip to Argentina. Allen's reporting indicates that apparently Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio handled cases of clergy sex abuse as any reasonable, cautious church leader of his generation would. We would suspect that he went through a learning process while acting within the constraints of civil and canon law.

To understand what his next steps as pope should be, it is helpful to know the circumstances under which Scicluna was being interviewed. The former prosecutor was being asked whether U.S. Cardinal Roger Mahony should attend and vote in the conclave. Just weeks before, the Los Angeles archdiocese had finally complied with a court order to release tens of thousands of documents that clearly showed Mahony and his lieutenants shuffling abuser priests from parish to parish, hiding their whereabouts from law enforcement and discussing legal strategies to keep abusers and the archdiocese safe from prosecution. The release of those documents was enough to cause the current archbishop of Los Angeles, José Gomez, to restrict Mahony from official archdiocesan duties. Mahony fought back with his personal blog, his Twitter account and his media savvy. He used his red hat to pull rank and forced Gomez to backpedal. Gomez declared that Mahony was still a priest and bishop in good standing. After hundreds of lives had been damaged and millions of dollars spent on futile legal delaying tactics, Mahony blithely boarded a plane for Rome, claiming a right to elect the new pope. Where is the justice in that?

Scicluna said the question of whether Mahony should join the conclave or not was a matter for the cardinal himself, a challenge for him to follow his conscience.

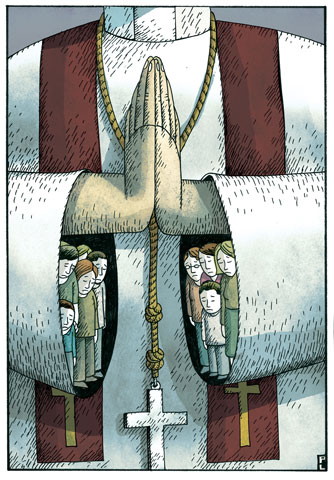

Mahony is Exhibit A for what Francis must do in the next phase of this crisis. It is no longer about frontline defense to protect children and remove offenders. The next phase of the crisis is all about accountability, the accountability of church leaders, bishops and chancery personnel who obstruct investigations or cover up crimes.

To date, the sex abuse crisis has been massively disruptive of the lives of priests and laypeople, but it has not made a huge difference in the lives of bishops because they have yet to be called to account. The Dallas Charter that can remove a priest or deacon from active ministry with one accusation of abuse is voluntary for bishops. Bishops in Lincoln, Neb., and Baker, Ore., have proven that, as have the leaders of seven Eastern rite eparchies in the United States who have never submitted to the charter. The bishop of Kansas City-St. Joseph, Mo., found guilty in two civil jurisdictions for failure to report suspected child abuse, remains in office.

Zero tolerance for clergy child abusers is now the universal law of the church. Francis' task is to lay down laws that will hold bishops liable for their actions and inactions, too. Bishops' accountability to the people they serve must also become the universal law of the church.