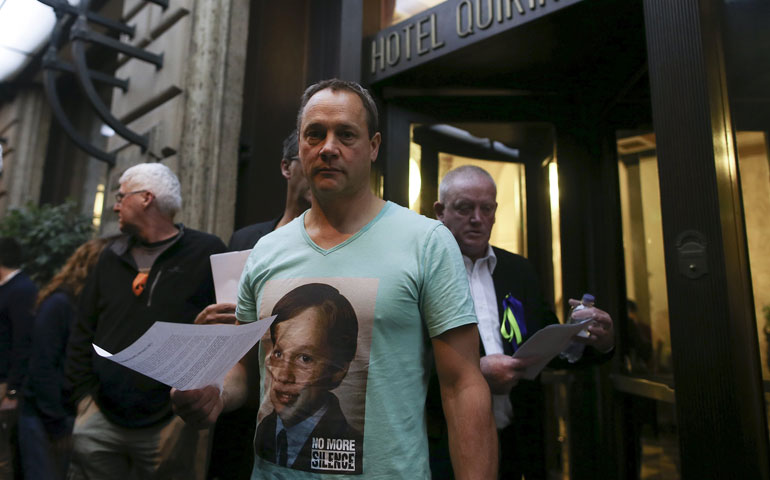

In Rome Feb. 28, Peter Blenkiron, center, a child sex abuse victim, looks on in front of the Hotel Quirinale, where Cardinal George Pell testified via video link to Australia’s Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in Sydney. Blenkiron’s T-shirt features a picture of himself when he was young. (CNS/Reuters/Alessandro Bianchi)

In some respects, the story of the Australian government inquiry into institutional responses to child sexual abuse is a story that can be told in numbers.

Since its first hearing three years ago, the inquiry -- the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse -- has received 29,223 telephone calls from victims and other interested parties, as well as 16,171 letters and emails. It has conducted 4,874 sessions in private (to provide, where requested, a safe and confidential environment for those testifying) and made 961 referrals to authorities, including police, many of which have resulted in arrests and charges.

The commission has also conducted nearly 40 public hearings around Australia looking into particular case studies of abuse -- such as the one in early March that saw the questioning via video link from Rome of the Australian church’s highest-ranking cleric, Cardinal George Pell.

It has produced more than a dozen research reports covering such subjects as the history of child sexual abuse legislation in Australia, and investigations into why institutions may have failed to identify and report child abuse.

Based on modeling undertaken by actuarial consultants, the commission estimates there may be as many as 60,000 surviving victims of child abuse in Australia. It has found that the most common decade in which abuse occurred was the 1960s (28 percent) followed by the 1970s (23 percent).

To put this in some perspective, in 1970, by which time around a third of the abuses had occurred, the total population of Australia was about 12.5 million -- more or less the present population of Pennsylvania or Ohio.

Just over 60 percent of survivors are male; 37 percent are female. The average age of abuse was just under 10 years for males and just over 10 years for females. In both cases, the overwhelming majority of offenders (89 percent) were male and, on average, children were abused over a period of 2.8 years.

The most common type of institution in which the abuse occurred (45 percent of reported cases) was one involving out-of-home care, such as orphanages, children’s homes and foster care. Around 60 percent of such institutions in which cases of abuse have emerged were faith-based organizations, with another 23 percent managed by government at either a state or federal (national) level.

Platform for victims

Numbers, of course, rarely tell the whole story. To the extent that the commission has been a cathartic experience both for individuals and more broadly, its impact is impossible to quantify.

Certainly, victims have been given a platform from which to tell their stories of abuse and survival. Just as importantly, they have been listened to and been shown respect. For far too many, this will have been the first time anything like this has happened to them since the initial harm was done.

With the media reporting on the work of the commission on a regular -- often daily -- basis, there is a community impact as well. Few people can now claim ignorance of the nature and long-term consequences of child abuse. This has already contributed to a new culture of openness about abuse replacing the old culture of secrecy and denial.

The commission has also shown just how extensive the incidence of child abuse was in the past. It has investigated allegations of abuse in the context of churches, yeshivas, yoga ashrams, performing arts centers, swimming clubs, government-run youth training camps, the criminal justice system, elite private schools, the Boy Scouts, and health care providers.

The obvious lesson learned is that, at a societal level, there has been far too little appreciation of the impact of lifelong suffering on the victims and far too much confidence in children’s resilience when they are abused.

The Catholic church, however, can take little comfort from the knowledge that it is hardly alone in shouldering a shameful past. Almost one in every three institutions so far examined in private sessions of the commission has been Catholic, and about one-third of all public sessions have involved Catholic dioceses, parishes, schools or other organizations.

In proportional terms, that may not be all that surprising: More than 25 percent of Australians claimed to be Catholic in the last census in 2011 and Catholic schools educate more than 20 percent of all Australian schoolchildren. Still, by the time the royal commission concludes in 2017, the Catholic church will be the one institution most examined on the child sexual abuse issue.

In the public theater surrounding the commission, the centrality of the Catholic church to the whole child sexual abuse situation remains firm. It was largely agitation from victims of Catholic clergy abuse -- and sympathetic media commentators -- that prompted former Prime Minister Julia Gillard to announce the royal commission in the first place.

‘You should come home’

Fairly or unfairly, it is the haughty public persona of Pell, together with the fact that he remains the most recognizable face of any religious organization in Australia, that has reinforced the connection between child abuse and the church in the popular imagination.

This was demonstrated again in the weeks leading up to Pell’s recent appearance -- his third -- before the commission when it was learned that, on medical advice, he would not fly back to Australia to testify. A small group of about 20 victims decided to fly to Rome to attend Pell’s appearance and they set up a social media Web page to raise money to cover their costs.

Prominent Australian comedian and musician Tim Minchin appeared on a television current affairs program performing a song he had written about Pell’s decision to stay in Rome. All proceeds, he said, would go to support the victims’ trip to Rome.

In the lyrics to the song, Minchin says that he is not a “fan” of Catholicism and refers to Pell as a “goddamn coward.” He then added: “I mean, with all due respect, dude, I think you are scum and I reckon you should come home.”

Within 24 hours, AU$200,000 (about US$150,200) had been promised to fund the victims’ trip to Rome.

This vignette says something about the situation in which the church now finds itself and, perhaps, something about the public and the royal commission.

On the first count, church authorities clearly are taking action in response to the revelations of past abuse and cover-ups. The Melbourne archdiocese, for instance, along with the Christian Brothers and Marist Brothers orders, is revisiting past settlements to victims.

A number of dioceses have introduced special child protection coordinators -- in the case of the Perth archdiocese, eventually one will be appointed in each of its 105 parishes. A new, independent entity to set, monitor and report on child protection standards across all dioceses and religious orders is in the process of being established.

But, just as clearly, many people have already switched off. Thus, when bishops speak publicly, they are often disbelieved; when they speak within the church, their words often struggle to take effect.

What many Catholics want to see is summed up by a submission last year to the royal commission by the activist group Catholics for Renewal. It claimed nothing short of “radical changes to the governance structure and practices” of the church would ever address the problem of abuse.

On the second count, there are members of the public -- Catholic and non-Catholic -- who seem to be growing a little impatient at the royal commission’s pace. After three years of hearings, what some people seem to want, including many of those who so quickly donated to the fund to allow victims to travel to Rome, is nothing less than a figurehead who can be held fully accountable for the horrors of the past. If the commission won’t provide it, they’ll try other means.

In the case of Pell, the desired upshot would at the very least amount to his sacking, which some of his critics are already demanding.

Much work remains

Meanwhile, the commission carries on. The federal government acknowledged the enormity of the task 18 months ago, when it agreed to extend the commission’s final reporting date by two years (until December 2017). The added expense (AU$126 million) will bring the total cost of this inquiry to slightly more than AU$500 million.

Later this year, the federal government is due to respond fully to a principal recommendation of the commission so far, which is to set up a single redress scheme for victims of abuse. This plan would involve the provision of counseling and psychological services to victims and also monetary payments of between AU$10,000 and AU$200,000 with an average payment estimated at AU$65,000. In all, the scheme is estimated to cost more than AU$4 billion over 10 years, with about half coming from government sources (state and federal) and private institutions contributing the rest.

The federal government has reversed its earlier opposition to taking part in such an initiative and now says it will help coordinate the plan. But it has yet to commit either to a startup date or to providing funding.

The two biggest states -- New South Wales and Victoria -- have also thrown their support behind the scheme, as has the Catholic church, despite acknowledging that its contribution could total AU$1 billion in additional payments.

Whether even that amount will repair the damage to the church’s reputation and moral authority seems doubtful.

[Chris McGillion is the author, with Damian Grace, of Reckoning: The Catholic Church and Child Sexual Abuse.]

Editor's note: After Australia's then-Prime Minister Julia Gillard convened the royal commission on the treatment of children in public and private institutions near the end of 2012, veteran Australian journalists Chris McGillion and Stephen Crittenden explained for NCR readers the background and context of that action. Read their stories at

Response to abuse has been slow, stymied by Vatican, by Chris McGillion

Australian commission to investigate child sex abuse allegations, by Stephen Crittenden