Analysis

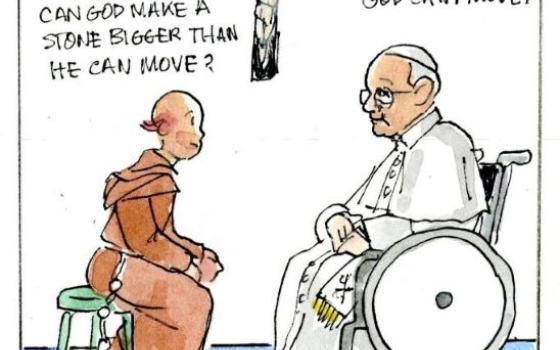

James Joyce famously described history as a nightmare from which his literary alter ego, Stephen Dedalus, was trying to awake. For the Catholic church today, there’s no need to await history; the present, defined by a massive worldwide sexual abuse crisis, is nightmare enough.

Recent events in Belgium are “news” only in the sense that they’re new to Belgians. For more than a decade, sex abuse scandals have devastated the church in other parts of the world, from the United States to Ireland and Germany, and raised hard questions about the corporate response of the Vatican and the personal history of Pope Benedict XVI.

To hear church leaders in Belgium say they need more time to ponder a response, therefore, cannot help but seem either disingenuous or naïve; by any reasonable standard of foresight, they should have seen this train wreck coming.

The trajectory of the Belgian story is eerily familiar: A single high-profile case (in this instance, revelations about Bishop Roger Vangheluwe) , followed by massive disclosures which suggest a pattern, followed by slow and ambivalent responses from church officials which fuel public outrage.

If past experience is a guide, what will eventually happen is that the bishops will make payments to victims, adopt tough policies to weed abusers out of the clerical ranks, commit themselves to full cooperation with police and other civil authorities, and learn a new language for talking about the crisis in public that accents compassion for victims and “zero tolerance” for crimes. When the dust settles, reasonable people will probably conclude that the Belgian church has cleaned up its act, but only after massive damage has been done.

The question therefore has to be asked: Why didn’t the church in Belgium take these steps before the crisis broke? Why does the Catholic church so often seem committed to a strategy of defusing the bomb after it’s already gone off?

There are two basic reasons.

First, bishops often seem ambivalent because they believe the Catholic church is being unfairly smeared. They point to data such as the John Jay study in the United States, the most exhaustive statistical analysis of the crisis in any country, which found that just four percent of priests serving over a fifty-year period faced credible charges of abuse. That’s no worse, and in some cases considerably better, than rates of abuse in other religious denominations, the public school system, and the juvenile justice system.

Officials also insist that media outlets and critics are quick to point out the failures of the church, but slow to credit its positive accomplishments. Belgium is a case in point: Lost in the hysteria over the findings of the Adriaenssens Commission is the point that this was a church-sponsored effort to root out the truth.

Criticism of the church, many bishops believe, is also fueled by lawyers hungry for payoffs, and by people who don’t like Catholic positions on controversial issues such as abortion and gay marriage.

All that may be true, but it misses the point of how people perceive these scandals. The Catholic church preaches sexual morality to the world, so to say that the rate of sexual abuse by priests is no worse than other institutions is a bit like saying the number of arsonists in the Fire Department is no greater than in the general public. Most people will not find that terribly reassuring.

Second, the Catholic church is ill-equipped to handle a global crisis. Despite the mythology of the church as rigidly hierarchical and ultra-centralized, the reality is that the church is top-down only on matters of doctrine. On everything else, it is actually one of the most decentralized institutions on earth. (There are 1.2 billion Catholics and only about 2,000 officials in the Vatican. That’s a ratio of citizens to bureaucrats that would be the envy of any other government on the planet.)

When the sexual abuse crisis erupts in a given country, it becomes a magnifying glass for the strengths and weaknesses of the local hierarchy. Where the bishops are unified and capable of mounting an effective response, the damage can be contained. Where they’re not, disaster ensues.

Germany is an instructive example. When the crisis broke in February, Archbishop Robert Zollitsch of Freiburg, President of the German bishops’ conference, swiftly apologized and admitted that the church had engaged in a pattern of cover-up. Hotlines were established for victims to report abuse, and the bishops adopted new policies which, among other things, require reporting all allegations of abuse to the police and civil prosecutors unless the victim objects.

When a well-known German bishop, Walter Mixa of Augsburg, was accused of physical abuse of children (though not sexual abuse), his resignation was swiftly accepted by Pope Benedict XVI, offering the German public a signal of accountability.

To be sure, many critics in Germany insist the church has not done enough, but the steps already taken have calmed the waters. The fact that they were able to accomplish all that in a span of roughly three months, from February to April, is nothing short of a miracle, given that the Catholic church legendarily thinks in centuries.

It remains to be seen whether the Belgian bishops will be similarly adroit. They do not seem to be off to an especially auspicious start, declining to offer a clear apology or admission of guilt, applauding a court ruling which held that the results of a police search of church property are inadmissible, and pleading for more time to cobble together a response.

Archbishop André-Joseph Léonard could perhaps learn something from his colleagues in Germany, the United States, and elsewhere, who have already learned the painful lesson that ambivalence and stalling won’t cut it.

Yet however inspired the Belgian bishops prove to be, they can’t operate in a vacuum. Their efforts will either be helped or hindered by the tone set by Pope Benedict XVI. His expression of “pain” over events in Belgium was a start, as was his unflinching admission on the opening day of his Sept. 16-19 trip to the United Kingdom that the church was not “sufficiently vigilant and not sufficiently quick and decisive to take the necessary measures” to combat the crisis.

Benedict’s pledge of “material, psychological and spiritual” support for victims is also welcome. At the same time, many observers believe more needs to be done.

One critical step would be a comprehensive global policy, which would feature two elements: Internal measures to remove abusers from the priesthood, and full cooperation with police and civil investigators. The Vatican has already published guidelines to that effect, but more needs to be done to give them teeth.

There’s also the question of accountability for bishops who have failed to manage the crisis. There are more than 5,000 Catholic bishops in the world, and only the pope can call them to task. Until there are meaningful systems of oversight, involving not just other bishops but also ordinary faithful, many observers will conclude that the church has not fully learned its lesson.

Healing must begin with an unmistakable indication that the church “gets it.” So far, Belgians seem to be still waiting for that reassurance – and until they do, little else will matter.

Finally, let there be no mistake: Belgium is the most recent front in the crisis, but it’s not likely to be the last. The question is, will the Catholic church elsewhere learn something, and perhaps, for once, defuse this bomb before it explodes?

[John L. Allen Jr. is NCR senior correspondent. His e-mail address is jallen@ncronline.org.]