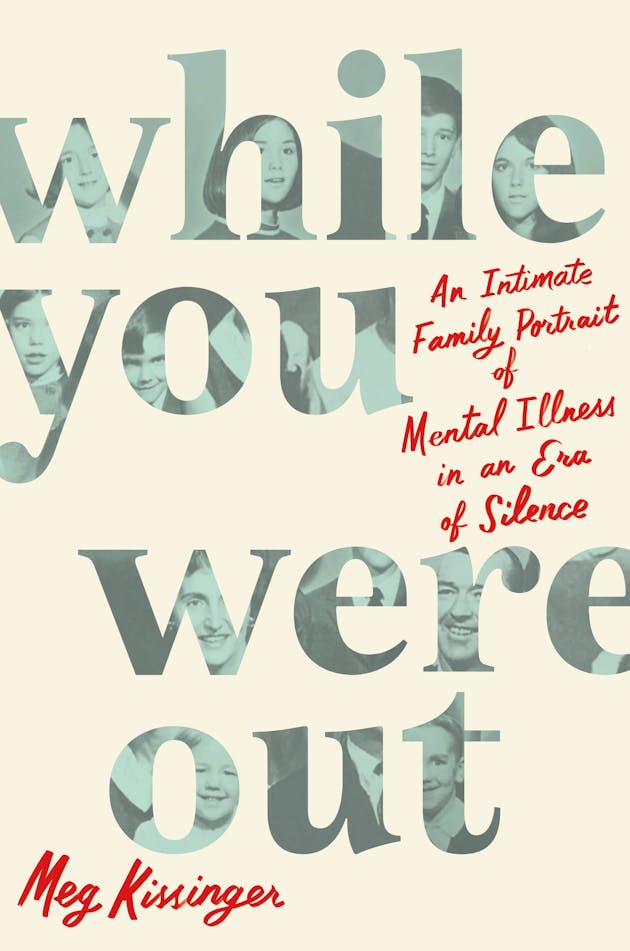

Meg Kissinger is pictured in a family portrait, far left in the top row. Kissinger, for many years a Milwaukee Journal Sentinel investigative journalist, has written the memoir While You Were Out: An Intimate Family Portrait of Mental Illness in an Era of Silence. (Courtesy of Meg Kissinger)

The breakdown of the nuclear family is a dominant theme in literature, particularly the novel and memoir, an obsession mirrored in the lurching changes since 1969 when America triumphantly landed men on the moon, followed by the long steady breakdown into today's swamp of disinformation, resurgent racism and mass gun violence. With Congress paralyzed by Christian reactionaries, will our national madness ever hit bottom?

In While You Were Out: An Intimate Family Portrait of Mental Illness in an Era of Silence, Meg Kissinger, for many years a Milwaukee Journal Sentinel investigative journalist, probes the pain and shame underlying her 1960s upbringing as the middle of eight children in the comforts of suburban Chicago, anchored by the Catholic Church. The narrative follows a tender reconstruction of the past, with bolts of terror as she explores why Nancy, the second oldest sister, and Danny, a younger brother, committed suicide many years apart. Despite the darkness, the memoir is long on humor and pathos, following siblings, Mom and Dad across time, entwined with Meg's own story.

While You Were Out has generated critical praise, TV interviews and speaking engagements for the author. "Kissinger brings passion and immediacy to the subject, sharing her own story and those of her sources with bracing frankness," noted Publishers Weekly. "As both a candid family portrait and a polemic against institutional neglect of people with mental illness, this delivers."

She discovered the book's taproot in 2006, when she was diagnosed with breast cancer. It sparked a midlife crisis, the start of a reckoning with her past. But, once recovered, she put that aside and threw herself in her reporting work. Kissinger and a colleague, Susanne Rust, began investigating household chemicals. They won a prestigious George Polk award and were finalists for a Pulitzer.

And then that same job began to bring her back to her past. Kissinger began confronting her family history as she started to report on the crisis in mental health awareness and treatment, issues that generated a huge response from Milwaukee readers. "I could never get over the number of frantic parents calling me in the newsroom, seeking help," she said — and she began to feel her own story could resonate with others, and offer help. Kissinger took the first stab at writing about the mental issues within her family, particularly her father's difficult and disruptive battle with bipolar disorder. "I tried at first to write it as fiction, being too scared to draw my family into it," she said. "But I realized I'm too beholden to facts."

She took a newsroom leave to teach journalism at her alma mater, DePauw University in Indiana. Then, in the spring of 2016, the Columbia Journalism School invited her to teach for a year as a visiting professor. At Columbia, Kissinger took a class on nonfiction writing with Samuel Freedman, a noted author and former New York Times reporter and columnist, "who drilled into us the importance of an airtight proposal. I also took a course on memoir by the wonderful Marion Roach Smith. She taught me the two most important lessons. First, your memoir is not about you. It's about what you learned because of what you went through, which can help the reader learn about one's self."

Meg Kissinger (Courtesy of Meg Kissinger)

A memoir, as Smith stressed, has to have an argument. "Mine was that shame is toxic and can kill you," Kissinger said. "I see now that I could not have written this book any earlier in my life. My work with Susanne Rust taught me to use hard-edged reporting chops and my time at Columbia gave me the chance for deep reflection. I lived not far from where Thomas Merton used to hang."

Alcoholism threads through the narrative as a slowly building leitmotif, as the author trains a searchlight on her mother, who had eight children. "Jean Kissinger, an erstwhile debutante with a genius IQ, now spent her days rubbing ointment on babies' blistered bottoms," she writes early on. Then, in the middle of the book, as Meg gives birth to her own son, she realizes, "I had no baby book, not even the slightest record of my first years. I didn't see a baby picture of myself until my mother found a few negatives while she was cleaning out a drawer when I was in college."

As the mother-daughter story line unfolds, Kissinger portrays Jean's midlife gravitation to Alcoholics Anonymous as a save-yourself response to an era when birth control was anathema to young Catholic mothers, and the nightly martinis shared with her upwardly mobile husband a sedation ritual for coping with life. She fought against serious bouts of depression and anxiety.

"For a long time while writing this book I thought it was about my mother," Kissinger said. "I spent most of my time with her trying to get more time with her, and then, when I finally got it, she got sick and died. My Dad used to say that when someone dies young, or youngish, 'the halo goes on tight.' That was certainly the case with how I regarded my mother after she died. I lionized her. It was only in researching this book that I came to see her more fully."

Advertisement

Kissinger started out angry at her mother. Nancy — the second eldest sister, a recluse at 19, damaged by drug use during her first year at college — committed suicide the day their mother left her alone in the care of a younger sister, Molly. But as Kissinger dove into her mother's past, she discovered a life filled with shame and secrecy: Jean's own mother had died young; the family hid the fact that one child had Down syndrome. "By exploring what my mother went through as a kid," Kissinger said, "I learned how to acknowledge her flaws and embrace her weakness as part of who she was — not something to sweep away and ignore, but to try to understand and love."

Shame and secrecy, she said, was a central part of another story she covered. Kissinger was a key reporter in the Journal Sentinel's coverage of the clergy abuse crisis that hit Milwaukee particularly hard in 2002. ABC News revealed that the archbishop, Fr. Rembert Weakland, had paid $450,000 to a former lover, a theology graduate student, prompting Weakland to step down.

"I admired Weakland and felt sad for him. Why didn't he say, 'I am a gay man'? I was mad at him for lying and covering up," Kissinger said. "What kind of church shames people into these awful secrets?"

She has been angry and frustrated at the institutional church for years, she said, but held close to her faith. "I feel peace at Mass. The sacraments do ground me. They calm me down and fill me up. It's nothing I earned," she said. "I feel faith is a gift for everyone. These days I go to 8:30 a.m. Sunday Mass in the middle of Milwaukee, a parish half-Black with a gospel choir church, about a quarter Hispanic and the rest of us old woke white ladies like me from the suburbs. It's thrilling."

And she is at peace now. Retired from teaching and journalism, Kissinger is a grandmother, and lecturer who travels to see family, and for conferences, speaking out about mental health awareness.

Just as in her reporting days, she is out there, working to make a difference.