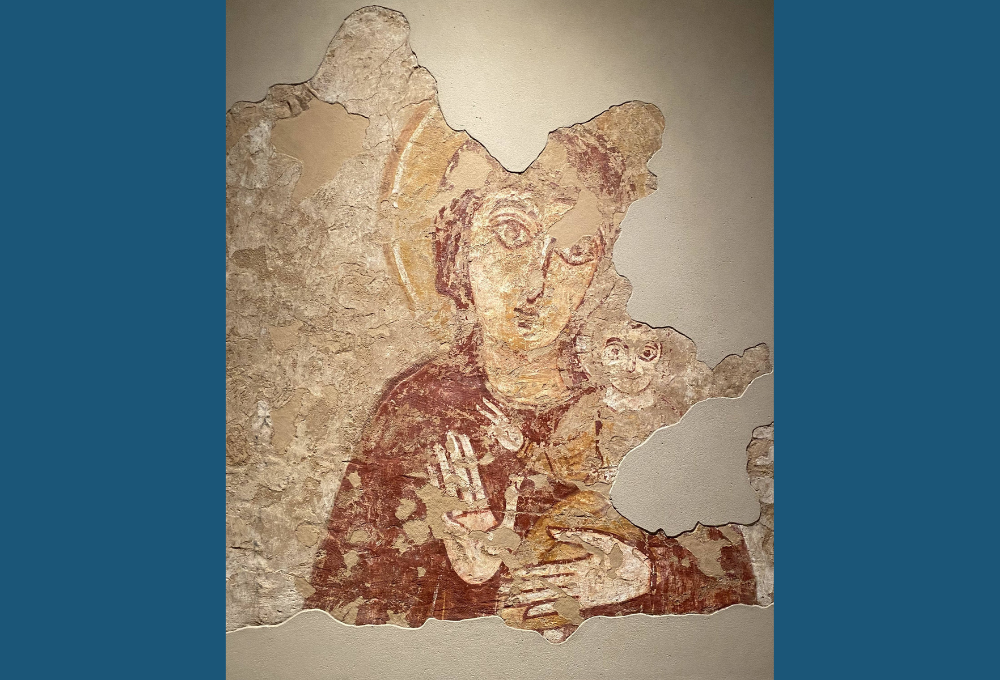

This eighth-century Nubian painting depicts the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus, modeled on the icon of the Virgin Hodegetria. It is part of "Africa & Byzantium" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through March 3 and at the Cleveland Museum of Art April 14-July 21. (Michael Centore)

It seemed a small detail at first: the stains of soot around the wick hole of a clay oil lamp from Tunisia, dated to the sixth century CE.

At the time, Tunisia — along with parts of present-day Morocco, Algeria, Libya and Egypt — would have been a province of the Byzantine Empire (395 CE-1453), whose political and ecclesiastical center was the "New Rome" of Constantinople.

The remnants of the flame that once lit the lamp cut across centuries of complex history. I was suddenly aware of the human dimensions of the object, that it had been used to illuminate a room or for devotional purposes.

The experience repeated itself throughout my viewing of "Africa & Byzantium," an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City through March 3 and the Cleveland Museum of Art from April 14 through July 21.

These objects have the ability to quietly stun us, to leap across time and show how boundaries were blurred between sacred and domestic space.

"Africa & Byzantium" brings together more than 160 objects from late antiquity through the 19th century, including mosaics, icons, textiles and illuminated manuscripts. In addition to North Africa, the exhibit surveys the relationship between the Byzantine Empire and the kingdoms of Nubia (in present-day Sudan) and Ethiopia.

While the heritage of Christianity in North Africa is known through figures such as St. Augustine of Hippo and St. Anthony of Egypt, the rich religious and cultural contributions of these southern kingdoms is often overlooked. The Aksumite Empire of Ethiopia adopted Christianity in 330 CE under the leadership of Ezana of Axsum, making it the second official Christian state after Armenia.

A Coptic wooden chalice case from the 18th century, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is painted with imagery on all four sides. (Michael Centore)

One striking Nubian piece on display is an eighth-century wall painting depicting the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus, modeled on the icon of the Virgin Hodegetria ("She Who Shows the Way"). With a few economical strokes of tempera on plaster, retaining a muted palette of dusty reds and browns, the artist manages to convey through Mary's doe-like eyes and open hand a feeling of tenderness and welcome.

Alongside the Hodegetria theme, the motif of the nursing virgin reappears throughout the exhibit. The 13th-century Icon with the Virgin Galaktotrophousa ("She Who Nourishes with Milk"), on loan from the Holy Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai, seems to emit a glow from within its polished amber surface. The image of the suckling Christ adds another layer to his humanity: We behold the mammalian bond between mother and child, their spiritual but also their physical connection.

We also gain new insight into Mary as a healer. A two-page spread from an Ethiopian manuscript of the Ta' ammәra Maryam ("Miracles of Mary") places her at the center of a series of events where she cures a man with a club foot.

Byzantium was a vibrantly multiethnic society. Like the strands of a tapestry, various languages and cultural and religious practices were woven into daily life. A psalter from the Egyptian monastic community of Dayr al-Suryan illustrates this with graphic clarity, as columns of text in five languages — Ethiopic, Syriac, Coptic, Arabic and Armenian — descend down the page.

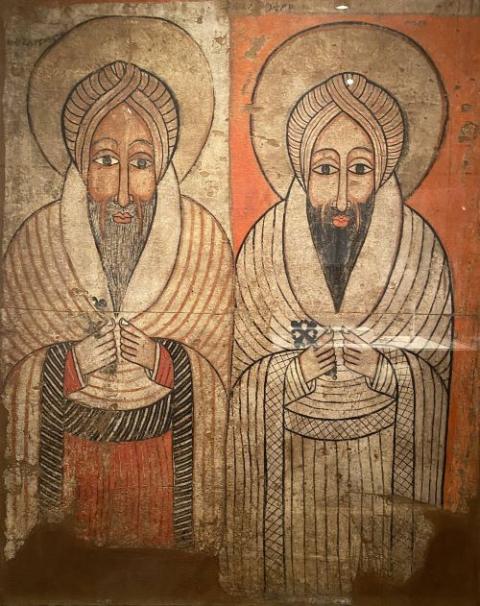

A wall painting from the second half of the 17th century depicts two Ethiopian monastic saints, Takla Haymanot and Ewostatewos. (Michael Centore)

Other objects from North African Jewish and Muslim communities, including mosaic floors from a Tunisian synagogue and folios from the Quran in Kufic script, speak to the multiplicity of faith practices in the southern Mediterranean.

I could have lingered for hours in front of some of the larger icons. One of the virgin and child flanked by angels and saints is believed to be among the oldest in existence, dating to the time of Emperor Justinian.

But like the Tunisian lamp, it was in the smaller, humble, handheld objects where the exhibit touched me on a human scale. These objects have the ability to quietly stun us, to leap across time and show how boundaries were blurred between sacred and domestic space.

One example is the collection of earthenware flasks bearing the image of the Coptic martyr St. Menas. We can imagine a pilgrim to the saint's gravesite purchasing one of these flasks, much in the way that modern-day pilgrims to Lourdes leave with vials of holy water.

Or take the diptych icon of St, George and the virgin and child, each in a different artistic style. About the size of a small paperback book, I pictured it in the niche of someone's house, or in the satchel of a traveler.

Though the Byzantine Empire fell to the Ottomans in 1453, its legacy radiated outward for centuries after. Several of the finest examples of religious art selected for the exhibition come from this post-Byzantine period.

Advertisement

A Coptic wooden chalice case from the 18th century is painted with imagery on all four sides. Appropriately, one side is dedicated to a depiction of the Last Supper. Arrayed in a blue tunic with gold striations, Christ places one hand on the Beloved Disciple while the other feeds a piece of bread to Judas, who crumples at the knees.

The image has all the chromatic dynamism, structural harmony, and spiritual power of a traditional icon. Seeing it adorn the side of a storage case is a reminder that, in the realm of liturgy, even the most utilitarian objects can be glorified.

Two Ethiopian processional crosses register a similar feeling. Though they were designed to be held aloft during the Divine Liturgy, they feature intricately etched figures and scenes. We sense the way art, faith and beauty were entwined in liturgical life, the care that was taken with even the subtlest detail.

I attended "Africa & Byzantium" two days before Ash Wednesday, and the exhibit was the ideal passage into Lent. Whether it was in the ragged edge of a Gospel manuscript or the well-worn patina of a pectoral cross, each object held a history of prayerful devotion.

As I was exiting the final gallery, I paused in front of a wall painting of two Ethiopian monastic saints, Takla Haymanot and Ewostatewos. The still simplicity of their gaze echoed back to that of the Virgin Mary in the Nubian wall painting. For a moment time collapsed, and I felt myself in the presence of a communion of peace.