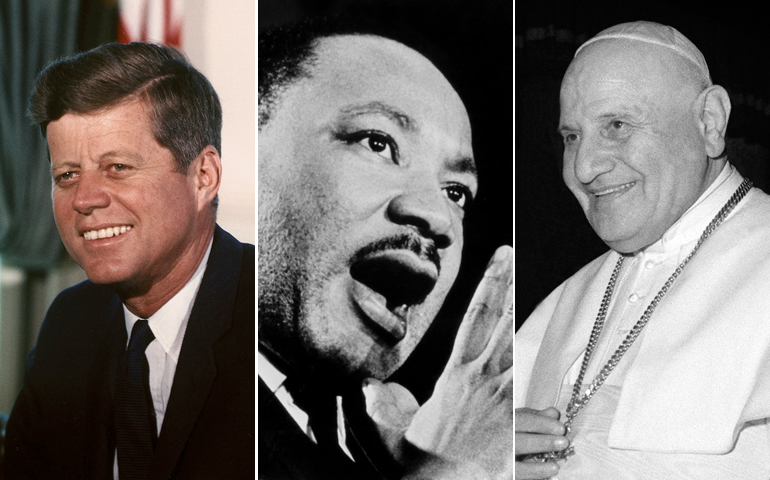

From left: President John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. and Blessed John XXIII (CNS photos)

It's 50 years later.

Fifty years after the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

Fifty years after the rise of Martin Luther King Jr.

Fifty years after the death of John XXIII.

Fifty years, that is, after a chorus of clarion calls for peace in foreign affairs, for equality in diversity, and for social justice as the essence of the faith. It is 50 years after three of the clearest, greatest calls for spiritual conversion in the history of the country.

Indeed, we have lived in an era of spiritual giants. And what do we have to show for it? Where are we now?

In his commencement speech at American University on June 10, 1963, Kennedy called for the most soul-changing conversion of heart at the height of the Cold War that the world had ever seen.

He challenged those graduates, the political leaders of the future, to understand that "total war makes no sense" in a world in which one single nuclear bomb was 10 times "all the Allied air forces in the second world war."

He had the effrontery to call for peace and collaboration with the Soviet Union in a country sick of soul from its fear of communism. Even then, the military budget of the United States had long before begun to sap American resources to the point of our own social ruination. We need to understand, he said to the young people of that era, that our own attitudes toward the meaning of peace in a newly global world is every bit as important as Russia's.

In a society long taught to hate and fear, to reject and resist the presence of communist Russia in the community of nations, he called these leaders of the next generation to remember the valor and suffering, the strength and creativity, the courage and undying commitment of the Russian people themselves in the face of their overwhelming losses in World War II.

In a world now threatened by nuclear pollution as well as nuclear annihilation, he called on those young people to realize that to confront an adversary with certain death was to force them to choose between humiliating retreat and total devastation in a war in which there would be lots of dead heroes but no winners.

And then he called for the United States to work with the Soviet Union, to help them achieve their ends so we might all achieve ours as well.

He called, in other words, for us, for the United States itself, to relinquish our national strategy of annihilation in order to pursue a strategy of peace.

It was a bold, brave, beautiful and holy commitment to spiritual conversion in a national ecology of hatred, war-mongering, military madness and political polarization.

And then, five months later, they killed him. Who? Who knows? But one thing for sure: It was someone who valued domination and death more than life, more than conversion, more than humanity -- their own or anyone else's.

And while all of that was going on, at the same time, 50 years ago, Martin Luther King cried out, too, for human equality, economic justice, the end of war and the unification of a nation that had consciously divided itself. And yet we still stop and frisk, stop and humiliate, any of those who live outside the dominant culture, marginalized by it, harassed by it.

Finally, in 1962, Pope John XXIII called the Catholic church, that bastion of monarchial yesterdays, beyond its resistance to the Reformation in which it had been cemented for more than 400 years. He called for the renewal of the very church itself, a force for life in the midst of a culture of death, a sign of unity in a war-making world rather than a wall of warriors devoted to the enshrinement of denominationalism. He called for a church that made the Gospel more important than the description of hell.

It was a torrent of conversion called for from every major institution and segment of population in the land: government, society and church.

Indeed, it has been a stirring 50 years. And where are we now?

We are at the end of half a century of internal warfare on every level: political, social and religious.

They warned us, all of them -- JFK, Martin and John -- to examine our policies and change our hearts, to open our arms and expand our souls, to stretch our minds beyond parochialism and chauvinism and domination or doom ourselves to watch the country destroy itself at its own hand.

And yet never has the country been so divided between haves and have-nots, between the affluent and the struggling, between the forces of spiritual change and the minions of control as now.

We talk global peace and continue to arm ourselves -- every man, woman and child on the street -- to the point of total vigilantism.

We have managed to get poorer, more divided and more doctrinaire in every arena. We have concentrated our wealth and destroyed our unions.

We have called the customs of the faith the essence of the faith. And so we have become a church in depression and disarray. We have spent our energies on the trappings of religion rather than on the heart of religion.

The American wealthy have managed to get more wealthy without the help of the American workers who created that wealth for them in the first place.

American society has swapped overt racism for a war on the 10 million immigrants we lured here to do the field work we did not want to do.

And our churches have split over rituals and language, taboo topics and issues of sexuality, gender discrimination and juvenile definitions of obedience despite the Second Vatican Council's attempt to make us all a church of adults.

The ecclesiastical clampdown on thought and discussion, on respect for the various theological positions of the various perspectives of the Christian community, on a willingness to even hear the cry of the new kinds of poor among us not only closed the windows of the church; it chose the answers from yesterday as sufficient to the questions of today.

We are as a people, in other words, halfway there and halfway not. We are, as a nation, a people and a church, a flagpole swaying in the wind.

We are at a tipping point.

The struggle has been too long; the confusion, too deep; and the politics of every institution, too unholy to abide much longer.

We are choosing now between discussion and dispute, between winning and growing, between the old and the newly imperative.

From where I stand, with an African-American in the White House, a South American from the Peronista era in the Vatican and 10 million undocumented immigrants among us, it looks as if we are at another moment of possible conversion. We are choosing between past and present, between life and death.

But with JFK and Martin and good Pope John gone, the only question now is: Which way are you yourself tilting? Who would know it? And why not?

Happy anniversary.

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Joan Chittister's column, From Where I Stand, is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.