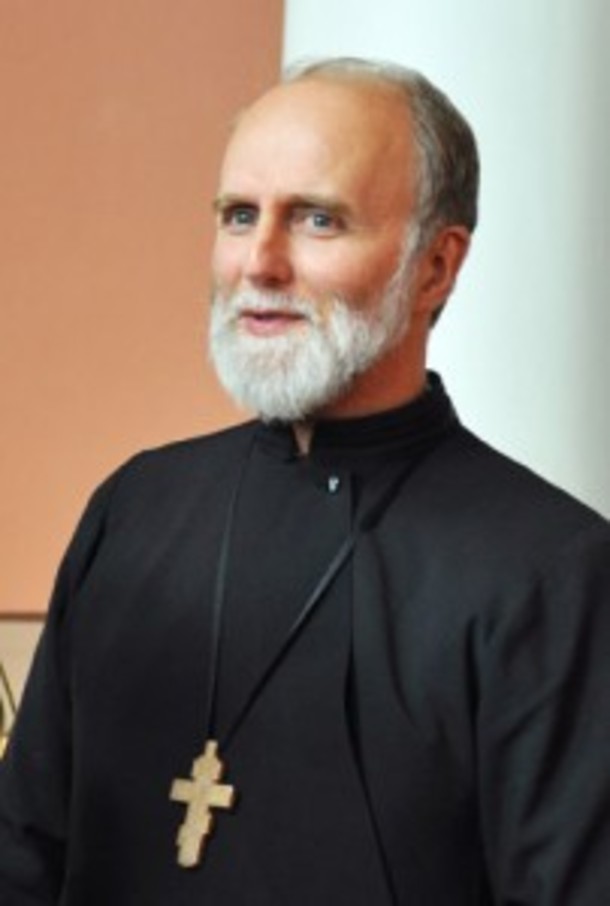

Bishop Borys Gudziak, president of the Ukrainian Catholic University

News about Pope Francis continues to flow at such a torrid pace that it's hard to digest one development before the next one hits. His Dec. 15 blockbuster interview with La Stampa is a case in point, with a shake-up at the Congregation for Bishops 24 hours later making it already seem ancient history.

Before moving on, however, it's worth highlighting what was arguably the pope's strongest language in that interview. As it happens, it wasn't his response to Rush Limbaugh's description of him as a "Marxist", but rather his comments on violent anti-Christian persecution around the world.

Francis suggested that the fellowship of suffering Christians share today could become the future of the press for unity, calling it the "ecumenism of blood."

"In some countries they kill Christians because they wear a cross or have a Bible, and before killing them they don't ask if they're Anglicans, Lutherans, Catholic or Orthodox," the pope said.

"We're united in blood, even if among ourselves we still haven't succeeded in taking the necessary steps towards unity, and perhaps the moment still hasn't arrived," he said.

Voices raised from various parts of the world over just the past week, including Syria, Iraq and Ukraine, seem to suggest he's on to something.

The mounting perils for Christians in Syria, where the armed opposition to President Bashar al-Assad appears increasingly dominated by Islamic radicals, were illustrated by Italian journalist Domenico Quirico in a Dec. 16 piece for La Stampa commenting on the pope's interview.

While reporting on the Syrian conflict in early April, Quirico was kidnapped by rebels and held for 152 days, repeatedly beaten and humiliated before eventually being released. The experience led Quirico to brand Syria, amid the carnage of its war, a "land of evil."

In his essay, Quirico wrote that his captors cared only that he was Christian, without any concern about what kind.

"The Salafist who tried to convert me didn't ask if I was Roman Catholic or Protestant," Quirico wrote. That Salafist, he said, addressed him only as "Christian," telling him, "Your gospels are false books full of lies and written to deceive.'"

Quirico described another conversation with a radical who said bragged of killing an entire Christian family.

"I killed them because they were Christians," he quoted the radical as saying, adding that the assassin didn't know if his victims were "Maronites, Catholics, Melkites, Chaldeans, Orthodox … just that they were Christians."

"The fact of being Christian was all it took to justify a death sentence," Quirico wrote.

Regarding Iraq, the country's senior Catholic leader described what he called a "mortal exodus" of Christians during a Dec. 14 speech in Rome.

According to Patriarch Louis Sako, more than 1,000 Christians have been killed in Iraq since the U.S.-led invasion in 2003, while scores of others have been "kidnapped and tortured." He said 62 churches and monasteries have been attacked.

Sako cited a recent estimate from the U.N. High Commission for Refugees that 850,000 Christians have left Iraq since 2003, by some estimates representing almost two-thirds of the country's Christian population.

That exodus, he added, includes both Orthodox and Catholics.

"We feel forgotten and isolated," Sako said. "We sometimes wonder, if they kill us all, what would be the reaction of Christians in the West? Would they do something then?"

Sako spoke as part of a Rome conference organized by the Religious Freedom Project at Georgetown University, part of the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs.

Meanwhile in Ukraine, voices within the country's Catholic minority are sounding alarms about mounting intimidation from security forces loyal to pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych.

The Greek Catholic Church, which claims three to five million followers in Ukraine out of a total population of 44 million, has long been an important force supporting democratic reform. The church's bishops recently issued a statement condemning crackdowns on protestors, while the Greek Catholic University in Lviv, the only Catholic university in the former Soviet sphere, offers one of the few public spaces where criticism of the government can be voiced.

Now, those Catholic activists find themselves at risk.

A Dec. 11 memorandum from officials at the university describes a series of ominous gestures from government officials.

"Police officers have already visited [the university] and interrogated the Dean of the School of Humanities and a few of his colleagues in an attempt to collect information about the students who participated in the demonstrations," the memo says.

"A few criminal cases have been opened against students and professors. Some students are put under psychological pressure while getting phone calls attempting to interrogate them about their involvement with protests, even warning them not to continue their participation in the demonstrations and insisting that they become 'internet silent'."

According to the memo, the government has also refused to recognize the university's rector and to withhold accreditation for its programs, ostensibly because the rector is a Ukrainian born in Poland and thus technically not a citizen. In reality, officials suspect the agenda is not tighten the screws.

As the protests in Ukraine have gathered force, they've also drawn support from other Christian denominations, including the Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate. There, too, Christians of different backgrounds find themselves in the same boat.

In his La Stampa interview, Francis referred to a Catholic pastor he'd known in Germany who was working on the beatification cause of a priest killed by the Nazis for teaching catechism to children. A Lutheran minister had been killed for the same offense, and Francis said the pastor went to his bishop and said he'd keep working on the cause only if the two figures could be beatified together.

"That's the ecumenism of blood," Francis said. "It exists today too, all you have to do is read the papers."

In light of current events in Syria, Iraq and Ukraine, the pope likely would get no argument in those neighborhoods.

[Follow John Allen on Twitter: @JohnLAllenJr.]