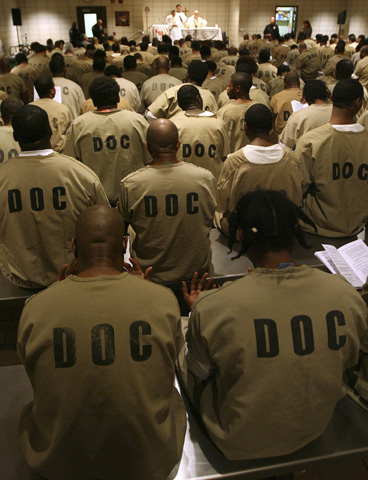

Maximum security inmates attend a Mass celebrated by Cardinal Francis George of Chicago in December 2007. (CNS/Catholic News World/Karen Callaway)

Herman Wallace, 71, was released from the Louisiana State Penitentiary after 42 years of solitary confinement last week. A member of the "Angola 3," Wallace experienced three days of freedom before dying Friday.

U.S. District Chief Judge Brian Jackson overturned Wallace's 1973 murder conviction and ordered his immediate release from prison Oct. 1. In Jackson's decision, he cited the "systematic exclusion of women from the grand jury panel that indicted [Wallace]," violating the 14th Amendment. Wallace received the news as he lay dying from liver cancer in a prison hospital ward. On Friday, surrounded by his legal team, activists and friends, Wallace died, far from the 6-by-9-foot cell where he had spent more than half of his life.

Wallace was charged with armed robbery in 1971 and sent to the Louisiana State Penitentiary, nicknamed "Angola" for the slave plantation that used to stand on its grounds. Wallace and Albert Woodfox, also serving time for an unrelated armed robbery, quickly established a prison chapter of the Black Panther Party. The men were determined to stop the rampant violence, sexual abuse and segregation inside Angola.

"Angola was a horror-show of corruption and abuse," according to The Times-Picayune. Inmates were regularly " 'sold' to each other to be used as 'sex slaves' or prostituted out to other inmates. ... The warden at the time, C. Murray Henderson, later confirmed this system of sexual slavery in his own book."

Within a year, Angola's Black Panther Party organized a literacy program, an after-meals exercise program, a self-defense class, several commissaries and an anti-rape campaign. Wallace explained, "It was through the practice of the above programs that we ... eventually brought rape almost to a standstill."

However, the Black Panther Party was brought to a standstill in 1972 after Officer Brent Miller was stabbed to death inside the prison. Wallace and Woodfox were immediately blamed, as was Robert King, another Black Panther Party member. The men maintained their innocence, but all three were convicted of murder in 1973 and placed in permanent solitary confinement.

"No physical evidence linking the men to the guard's murder has ever been found; potentially exculpatory DNA evidence has been lost; and the convictions were based on questionable inmate testimony," according to an American Civil Liberties Union report.

The state's main witness, Hezekiah Brown, originally claimed he did not know anything about Miller's death. In court, Brown changed his story, testifying that Wallace, Woodfox and two other men stabbed Miller to death with a lawn mower blade. Under oath, Brown swore he was receiving no favors in exchange for his testimony.

"The warden at the time, Murray Henderson, admitted years later that he promised Brown a pardon in exchange for his statement. Brown also got to live at the dog pen [the dog-caretaker house on prison grounds]," according to NPR.

The warden would visit Brown at the dog-pen, bringing him cakes as well as a carton of cigarettes once a week. "At a time when inmates would pay another inmate a pack of cigarettes to stab someone, former prisoners say a whole carton could get you a lot," NPR said.

Wallace, Woodfox and King became known as the Angola 3, and their supporters refer to them as political prisoners. King spent 29 years in solitary confinement before he was exonerated of Miller's murder and released in 2001. Woodfox remains in solitary, though his conviction has been overturned three times, most recently in February.

Juan Mendez, the U.N. special rapporteur on torture, said Monday, "Keeping Albert Woodfox in solitary confinement for more than four decades clearly amounts to torture and it should be lifted immediately."

Warden Burl Cain refuses to move Woodfox back to general population, and at Woodfox's second deposition in 2008, Cain said, "I still know that he is still trying to practice Black Pantherism.

"I still would not want him walking around my prison, because he would organize the young new inmates. I would have me all kinds of problems, more than I could stand, and I would have the whites chasing after them."

The tireless activism of the Angola 3, particularly Wallace, led Ebony magazine to write, "Although Nelson Mandela and Herman Wallace each fought for racial equity in their respective countries, South Africa and the United States, in the eyes of their governments these men will leave two very different legacies." Wallace's New York Times obituary similarly states, "Even from solitary, Mr. Wallace worked to improve prison conditions."

Days before his death, Wallace was still fighting for justice. His attorneys wrote, "It is Mr. Wallace's hope that this litigation will help ensure that others, including his lifelong friend and fellow Angola 3 member, Albert Woodfox, do not continue to suffer such cruel and unusual confinement even after Mr. Wallace is gone."

District Attorney Sam D'Aquilla demanded a retrial, and a jury re-indicted Wallace for Miller's murder a day before his death.

Wallace's friends chose not to give him the news. They reported that he murmured "I am free, I am free" moments before he passed away, far from Angola's walls.