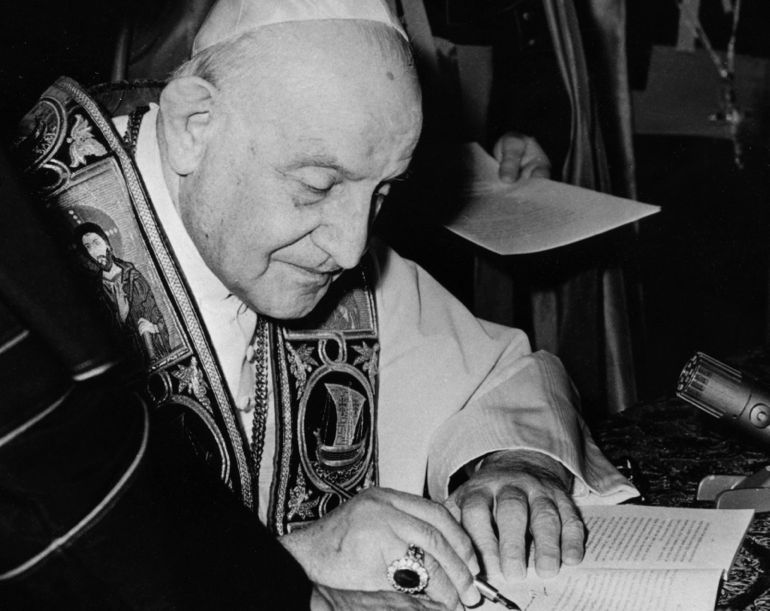

Pope John XXIII signing Pacem in Terris (CNS photo)

It was a most remarkable time. A pope had caught the attention of the entire world and was visibly leading believers and nonbelievers alike in much-needed moral leadership.

Pacem in Terris, Pope John XXIII's signature encyclical, was issued 50 years ago today.

His sense of optimism exhibited in the document was infectious. His idea of inclusiveness changed the Catholic mindset. His belief in the human spirit and the need to free it from self-imposed captivity caught the imagination of the world.

A year in the making, our beloved John, now Blessed John, knew the document would be his last word of encouragement. He knew he would not have another chance to address the critical issue of world peace. He was dying of cancer, and his pontificate would end only two months after he issued Pacem in Terris.

Yes, it was a remarkable undertaking, even revolutionary. He addressed the encyclical not only to Catholics but to "all men of good will." That was a first for a papal document in the modern era.

The basic premise of John's thinking was that the bonds of humanity bind all people and all nations, and seen together, these bonds are more important that any doctrinal, national or ethnic differences. Based on these common bonds and common human aspirations, he called for an end to a climate of fear and for new openness to understanding. Specifically, he called for the end to the arms race through effective arms controls well before such discussions began between the world's superpowers.

No social encyclical since it has gained such non-Catholic attention. In an unprecedented move, the United Nations held a conference to examine the contents of the encyclical.

Pacem in Terris grew out of challenges and opportunities John saw facing the world.

It was his personal response to the deep international tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, most visible one year earlier, during the Cuban missile crisis.

According to Pope John's personal secretary, the pontiff began pondering the opus that would one day be called Pacem in Terris one long night during the crisis. He began by composing what he thought would be a message to President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev aimed at bringing the two warring sides together.

In the process, he unequivocally ended up declaring that nuclear weapons had to be banned from the planet.

"Justice, right reason, and the recognition of man's dignity cry out insistently for a cessation to the arms race," he wrote. "The stockpiles of armaments which have been built up in various countries must be reduced all round and simultaneously by the parties concerned. Nuclear weapons must be banned. A general agreement must be reached on a suitable disarmament program, with an effective system of mutual control."

Years later, Catholic author Gordon Zahn wrote that the "longer range effect of Pacem in Terris was to tip the theological scales against nuclear war and deterrence."

Pope John proposed a new world order to be built on four pillars: truth, justice, love and freedom.

Truth will build peace if every individual sincerely acknowledges not only his rights, but also his own duties towards others.

Justice will build peace if in practice everyone respects the rights of others and actually fulfills his duties towards them.

Love will build peace if people feel the needs of others as their own and share what they have with others, especially the values of mind and spirit, which they possess.

Freedom will build peace and make it thrive if, in the choice of the means to that end, people act according to reason and assume responsibility for their own actions.

The encyclical represented for the first time a fundamental Catholic embrace of the human rights tradition as found in the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights. Many in the church at the time saw this as a church reversal and a moment in which Catholic values and wider values based on human dignity finally met on common grounds.

John's thoughts on rights and freedom as one of those rights eventually found their way two years later into the important Second Vatican Council document Church in the Modern World.

Pondering the world and the human family, John saw goodness as the default premise. Out of this goodness, though marred by sin, came common human aspirations and progressive development. He looked at the world and saw human progress, listing some of these advances "as signs of the times," noting:

- people were becoming increasingly conscious of their human dignity;

- women and workers were claiming their basic rights;

- nations were achieving independence, breaking out of colonialism. They were founding governments on constitutions, included fundamental human rights;

- a new sense of world community was growing across the planet;

- national economies were growing more interdependent;

- people were rejecting violence as a means to settle disputes; and

- the entire human family was entering the era of the atom and the space/information age.

Part of the genius of the document was that John was able to present it in a language that resonated with believers and nonbelievers alike.

It was "at once eloquent and practical, diagnostic and therapeutic, historical and contemporary. Most important of all, it sets men's minds in a new direction, enabling them to break loose from notions of inevitability, defeatism, and despair," Norman Cousins wrote in Continuum in the summer of 1963.

Fifty years later, arms control negotiations continue to stumble forward even as nations continue to build and threaten to use these weapons. The U.S. maintains the largest stockpile of such weapons. World peace has not been achieved, but human longings for peace are no less palpable.

It will take the optimism and the faith of Pope John to move us down the path. Rekindling his commitment to peace building, his optimism about human nature and possibilities, his faith in the future, are timely and necessary undertakings. We should recommit ourselves to his vision.

[Thomas C. Fox is NCR publisher. Follow him on Twitter: @NCRTomFox.]