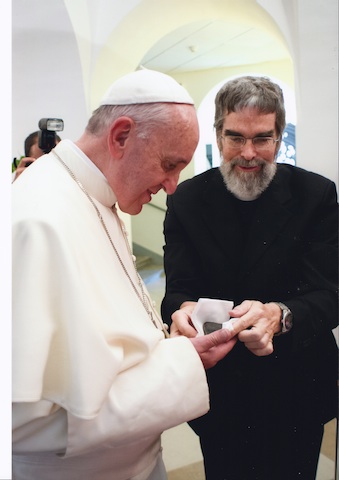

Pope Francis inspects a Mars rock with Jesuit Br. Guy Consolmagno.

"I'm not religious. I believe in science," said my TV and film costume designer friend Jennifer in a recent conversation. I asked her what she meant, and she responded, "I'm not smart enough to understand it all, but I trust in a system that values rational evaluation."

I'm not exactly surprised by how many people regard religion and science as two opposing forces. We all remember that unfortunate tiff the church had with Galileo. (But we can't forget Rome did apologize -- sure, it may have taken a few centuries, but it's the thought that counts, right?) So, yes, I agree, there are some complications in the relationship between science and faith, but generalizing Catholicism as science-phobic just doesn't sit well with me ... almost as much as the idea that faith doesn't value rational evaluation.

Now, I'm not trying to get into one of those debates Christopher Hitchens used to have with religious people. It's just, particularly as a Jesuit, I feel like I should make a PSA to clear a few things up. To put it simply, we LOVE science. (Well, not me personally -- I'm definitely more of a humanities guy. There's a reason I'm working in the entertainment industry and not teaching organic chem. But on the whole, as a group, there are plenty of us who just can't get enough of equations, theorems, and the like.) Still not convinced? OK. That Big Bang theory Christians supposedly hate? A Jesuit came up with it [1]. The first mathematically correct theory of flight? That was a Jesuit, too [2]. This year's Carl Sagan Medal award recipient? You guessed it! Another Jesuit!

The award's recipient, Br. Guy Consolmagno, works at the Vatican Observatory, a center whose mere existence some find perplexing. The church actually has a long history with astronomy, initially constructing the Gregorian Tower in 1580 so Jesuit Fr. Christoph Clavius could collect data to create the Gregorian calendar we use today. Since Clavius, there's been a long line of Jesuit astronomers. Indeed, there are over 30 craters on the moon named after Jesuits. (They were the ones making the maps, so are you surprised?) Since the 1930s, the pope has entrusted the Vatican Observatory to us, and Jesuits continue to work in the observatory's headquarters in Italy and, more recently, in its second location in Arizona (a place with a lot less light pollution than Rome), mapping the universe, studying meteorites and asteroids and, yes, looking for signs of extraterrestrial life.

Side note: I absolutely love space. As a kid, I'd rush home after 5 p.m. Mass at St. Rita's to catch "Space: 1999." I waited in line several times for "Star Wars," and I was thrilled to read Mary Doria Russell's The Sparrow about Jesuits in space [3]. Of course it's probably telling that it's stories about space that captivate me, not necessarily the science. But I think the same sense of wonder that excites people who love space stories is the same kind of wonder that excites those who spend their lifetime studying its scientific intricacies.

Brother Guy put it well when my team and I interviewed him for this week's video: "Looking at the sky reminds you that there's more to the universe than what's for lunch." Indeed, there's something so universal about looking up on a clear night, exclaiming, "Wow!" and letting yourself imagine the infinite possibilities. As Guy says, "Looking at the stars and wondering what they are about and how we fit in -- that is something that makes us human."

Now back to this idea that you can't be religious and scientific. There's this assumption out there held by many nonreligious AND religious folks that if you're religious, you believe you have all the answers and you end up abandoning all rational evaluation and curiosity. OK, I'm a priest with degrees in theology and philosophy, and I'll be the first to admit I don't have all the answers. (On my best days, I'll have ONE answer, if I'm lucky.) And why would I abandon rational evaluation using the mind God gave me? Indeed, the more you know, the deeper you go into your relationship with God, the more you realize you simply don't know. Brother Guy said it well at a talk at the Mount Street Jesuit Centre in London:

Faith is not accepting a bunch of facts in the absence of evidence. It is making choices in the absence of all the facts ... whether it is your choice of school, or job, who you will marry, where you will live. When you made those choices, there was no way you could know how it would turn out. That's life, making choices in the absence of sufficient data. But you make these choices in the expectation that things will turn out well. That's faith. Sometimes that expectation is going to be shattered, but you go ahead anyway; what else can you do?

For Brother Guy and the other Jesuit scientists, their faith doesn't dictate what facts to believe. Their faith gives them the reason to go looking to try to understand those facts. Healthy faith requires curiosity and doubt, and so does good science. "Science is not the facts, it's the conversation," he says. In order to go deeper into spirituality or science, you have to get comfortable with mystery and resist the temptation for black-and-white simplification.

I write all this acknowledging that I'm neither a theologian nor a scientist, but that's the beauty of spirit and science: No one's excluded. We're all permitted to wonder, to "converse," about these things and consider our place in it all. I suppose the same is true for good storytelling. If I produce a compelling film, the opportunity for it to resonate shouldn't be reserved for a select few.

In a world where technology is king (it seemed like discussion about the new iPhone 6 momentarily trumped the Islamic State, Ebola, and immigration on Tuesday) and so many feel like they must choose between science and spirituality, the Vatican Observatory is worth learning about. Give the video a look, and let's remember those Jesuit scientists the next time we come across one of those fundamentalist religious types who says science is a farce. But let's also think of them the next time someone tells us they have all the answers in science and have no need for spirit.

And if you'll permit me, consider going outside tonight and looking up at that mysterious sky and indulge in a little wonder! If you're feeling particularly adventurous, you may want to think of this quote by Jesuit scientist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin: "Someday, after mastering the winds, the waves, the tides and gravity, we shall harness for God the energies of love, and then, for a second time in the history of the world, man will have discovered fire."

Science and faith as two opposing forces? I don't think so.

______________________________________________

[1] Jesuit Fr. Georges Lemaître proposed the Big Bang theory in 1927.

[2] Jesuit Fr. Francesco Lana, considered "the father of aeronautics," published Prodromo dell'Arte Maestra (1670) as the "first publication to establish a theory of aerial navigation verified by mathematical accuracy and clearness of perception" (source).

[3] Mary became a friend, and her son ended up interning at Loyola Productions. Check out her blog at http://www.marydoriarussell.net.