With a modest degree of fanfare, Crisis magazine “returned” yesterday. The magazine begun by Ralph McInerny and Michael Novak in 1982 has been, with First Things, the place where Catholic neo-conservatives have tried to shape debate both within the Church and within the polity, and they have met with some success on both fronts.

Crisis has been operating, essentially, as “Inside Catholic” the past few years and, already, one of the changes is regrettable: The previous homepage had a listing of recent posts, mostly from rightwing Catholic blogs and, whenever it was a slow news day and I was looking for something to write about, I could go to Inside Catholic, scroll down the list and find something repugnant to write about. Now, the thought of having to add “Father Z” to my favorites’ page seems a dreadful prospect.

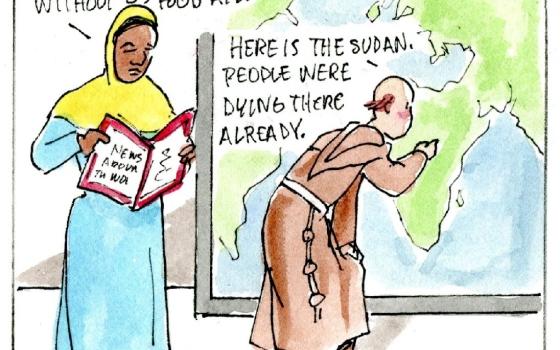

The essay announcing the rebirth of Crisis was penned by its editor, Brian Saint-Paul, and it is as subtle as a brick. The photo accompanying the essay has no particular Catholic significance. It is, instead, a photograph of a Civil War battlefield, the long lonely road stretching into the distance, a split-rail fence on one side, the kind behind which Union or Rebel troops once stood. I would submit that the challenges facing America, great though they are, do not really bear comparison with the Civil War. Nor did the “crisis” in the Church the original founders of Crisis perceived in 1982, when the magazine was founded, resemble the Civil War. Memo to neo-cons: You are no Lincoln.

I can see how some conservatives worried in 1982 that the Church was in danger of becoming, to use Cardinal George’s happy phrase, “chaplain to the status quo.” At Vatican II and in the years afterwards, there was an opening to the world that was different from what went before, and in that engagement, some slipped in to an easy endorsement of the ways of the world. But, if there was too much in the way of cultural conformism at that time, the neo-con response was hardly counter-cultural. The writers at Crisis, then and now, did not and do not engage the genuinely non-conformist approach to the world that one discerns in the writings of, say, Hans Urs von Balthasar. The neo-con response has amounted to little more than an attempt to baptize the Republican Party and modern capitalism. They may conform differently to the world than their more liberal ideological opponents, but it is conformity nonetheless and a particularly unimaginative conformity at that.

Saint-Paul’s essay asserts that things have gotten better since 1982. He writes, “The American Catholic Church in 2011 is in better shape — and is better led — than the one Ralph and Michael contended with in 1982. Theological sanity returned through the pontificates of Blessed John Paul II and Benedict XVI, and the temporal assertions of the Church are no longer reliably leftward.” It is difficult to see the basis for this claim apart from a few stray sentences in Centesimus Annus. Certainly, the vision put forth by Pope Benedict in Caritas in Veritate does not suggest that the admitted danger of human freedom and dignity being compromised before the power of an impersonal bureaucracy be countered by turning to the yet more impersonal market forces the Catholic neo-cons champion.

The assertion that the Church in America is in better shape in 2011 also entails other difficulties. You would not know it from Saint-Paul’s essay, but the Catholic Church has also been, and still is, in the midst of its greatest –dare we say it – crisis in its history, the crisis brought on by episcopal malfeasance in the face of clergy sex abuse of minors.

There is also a great misreading of Church History in Saint-Paul’s claim. Pope Paul VI and the bishops of the United States were not, in 1981, theologically “insane” so it is difficult to posit a return to sanity. Indeed, what is most striking in 2011 is the degree of continuity between the pontificates of Paul VI and John Paul II. The same can be said about the hierarchy in the United States. Does Saint-Paul think Cardinal Cooke was “insane” or Archbishop Hickey or Cardinal Madeiros? Were these men less committed to the pro-life cause than their predecessors? Were they “liberals” in any meaningful sense of the word? Is the letter sent by Bishop Blaire and Bishop Hubbard to the U.S. Senate, referenced yesterday, not in the tradition of a strong commitment to social justice of the kind we associate with Cardinals Sheehan and Dearden and Bernardin?

I welcome the entrance of any serious journal of commentary to the ranks of Catholic journalism. We need many voices in the public square. But, all this bowing and scraping before the pagan god of the free market, all this invocation of a sense of crisis, all this besmirching of the reputation of outstanding, earlier bishops and this denigration of Pope Montini, all this suggests a hubris and self-importance that seems excessive when you consider the paltry contributions to Catholic thought the neo-cons offer. Above all, the neo-cons fail to confront the most basic difficulty facing American Catholics of all ideological stripes: Our culture places a priority for freedom before a priority for truth, and our Church demands that freedom and truth must walk together. It is a big difficulty and the neo-cons are loathe to even acknowledge it.

Crisis magazine, Saint-Paul notes, began in a small office at the University of Notre Dame. It has moved to K Street. The move is not only physical, it is attitudinal, and it speaks to the essential problem of today’s Catholic neo-cons. And, funny thing is, on K Street, you don't really do battle, you do lunch. The photo accompanying Mr. Saint-Paul's essay should not be a battlefield, it should be the Palm. That is where the heart of today's Catholic neo-cons really beats with fervor.