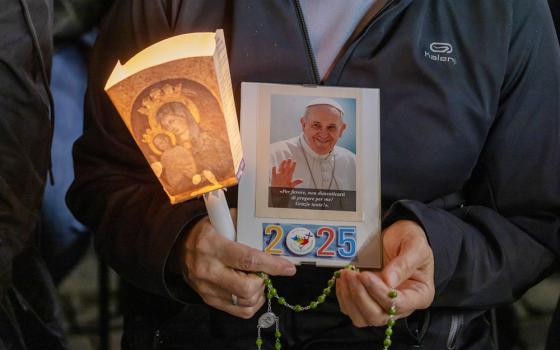

Recent news headlines tell of pastors in Italy reporting that "hundreds of thousands" of Italian Catholics, inspired by Pope Francis, are returning to the church. Other parts of the world have seen upticks in Mass attendance, as well, though not yet in the U.S.

This is one of the "Francis side effects" for which we can be grateful. He has not been trying to make what were once termed "fallen away" Catholics feel guilty for missing Mass or being sinners but rather simply to make them feel welcome in a church he describes not in lofty abstract theological terms but in ways that speak to the everyday experience of ordinary people.

For Francis, and therefore for us, the church is a loving "Mamma" who loves all her children, or a "field hospital" that provides bandages for those wounded by heartbreak and beds for those in need of comfort and shelter. Who would not be drawn to a pope who says that the church is not a bureaucracy? And who says that its bishops should come not from the ranks of the termite-like officials who feed daily off the judgments they make on what they think is sin, but from the brotherhood of pastors who feed daily the spiritually famished whose sorrows, as they well know, are far deeper than their sins?

Even atheists, who have felt pretty good about themselves and their highly publicized rejection of belief, don't quite know what to make of a pope who offers them dignity rather than damnation. This Francis side effect has so shaken one group of American atheists that they are sending comedians as missionaries to seek out converts.

Even some cardinals, like the redoubtable Raymond Burke, late of St. Louis and now of Rome, have hurried to reassure traditional Catholics that the views of Francis and Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI are in complete harmony on liturgical and other questions. What is Francis doing that he can make both atheists and high ranking prelates defensive at the same time?

Perhaps the best answer is found in Georgetown theology professor John O'Malley's 2010 book What Happened at Vatican II? He cites the concepts of aggiornamento, Italian for "updating;" development, "in the sense of unfolding or evolving" and ressourcement, French for "return to the source." These are not fixed-in-place-forever concepts but dynamic or living notions, keyed to growth and change, led the council fathers to react "against interpretations of Catholicism that … reduced it to simplistic and ahistorical formulas."

Vatican II, O'Malley tells us, revitalized theology by abandoning the mentality that "saw great social entities like the church sailing like hermetically sealed and fully defined substance through the sea of history without being affected by it." Perhaps the best example of this was the painful divide elder theologians forced onto the concept of human personality, so that sexual feelings were considered always potentially sinful and, as a result, being human meant feeling forever guilty.

One of the main Francis side effects is a return to human experience from inaccurate and cruel abstractions about it. Science and its discoveries have never laid siege to religion, in which it has no direct interest. The heavily guarded fortress of abstract faith has fallen to something much simpler, the everyday human experience of ordinary men and women. The latter know the difference between the symphonic language of abstract, theological reflection, and the plainchant vocabulary with which they name everything they experience from exhilarating love to numbing loss.

Human experience resembles the battered moon that tracks us in cycles of light and darkness, of life and death, now seeking out and now stealing away from the sun that gives it light and symbolizes eternity. When it blooms fully the moon blesses love and lovers, but hammered into a scythe, it hacks away at our light and touches off deep mortal longings that focus us on ourselves just-as-we-are in the world just-as-it-is. When we enter the authentic atmosphere of our own experience the interpretations forced on us by the world's vast managing institutions tumble away like space debris.

We evaluate claims about us or about teachings aimed at us by empirical means, by measuring them against our own experience of them. Of religious doctrine healthy people can ask: Does this teaching or assertion match what I have known or felt or learned, usually the hard way, in my experience of life itself?

Just as the body rejects tissue that does not match it, so, too, healthy men and women ultimately reject interpretations that do not match their experience of them. The sense of the community expresses itself whenever the larger and healthier number of believers agrees on any matter even if their conclusion contradicts some ecclesiastical theory or command. We call this common sense and the church has always recognized it as an infallible test of whether a teaching can be held or not. It has been called one of the munera, or "gifts," of the church.

It is known as reception, and it means that the church cannot teach something as true if the people who constitute the church do not accept it. The canon of the books of the Bible was set through reception.

The main Francis side effect is his restoration of confidence in the people who are the church. He speaks to them directly about things with which they are familiar in their everyday pursuit of love and justice. Francis makes people feel better about themselves as believers. It is unlikely that comedians can do that for atheists.

Ordinarily, people are warned about the potentially harmful side effects of some medication or treatment. No such warning need be applied to the Francis side effect of ratifying the good sense of good people as they work through the opportunities and challenges of life.

And that is something for which we can be truly thankful.

[Eugene Cullen Kennedy is emeritus professor of psychology at Loyola University, Chicago.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Eugene Cullen Kennedy's column, Bulletins from the Human Side, is posted. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.