COLUMN

Any logician worth his or her salt will confirm that deduction, moving from the general to the specific, is a much stronger form of argument than induction, which works the other way around. The problem with drawing broad conclusions from specific cases is that a counter-example may be lurking just around the corner.

Even so, I’m going to try my hand at some induction this week, teasing out broad implications from three specific storylines percolating around the Catholic world.

As a preview of coming attractions, here are the conclusions to which I’ll build:

- The Catholic church may be entering a season of major reform regarding money management.

- Religious freedom is destined to be the towering diplomatic and political priority of the Vatican and the global church in the 21st century.

- Against all odds, there’s hope for overcoming polarization in American Catholic life -- and it stems from an area where those divisions seem especially pronounced, Catholic healthcare.

With that, as the great logician Sherlock Holmes would say, the game is afoot.

* * *

The city of Maribor in northern Slovenia is usually a fairly quiet place, known mostly as a popular Alpine ski resort. Yet today the Archdiocese of Maribor faces what one popular Italian media outlet has described, perhaps a bit breathlessly, as “one of the most devastating financial disasters in the history of the church.”

In a nutshell, the Italian weekly L’Espresso reported on Jan. 21 that after decades of risky investments, the Maribor archdiocese is now in hock to the tune of more than $1 billion, and that a network of banks, real estate firms, and media companies owned by the archdiocese is on the brink of collapse, potentially wiping out the savings of thousands of small investors.

Earlier this week, the Maribor archdiocese released a detailed statement, the gist of which is that things aren’t quite that bad. The companies cited in the article, it said, are actually independent, even if the archdiocese and two smaller Slovenian dioceses own a controlling stake. As of the end of 2010, it said, the total debt of the archdiocese itself was just $24 million, and it pays its bills on time.

That said, the statement acknowledged a “moral responsibility” to protect investors in companies owned by the church, and said the archdiocese has pledged some of its property to try to stem the bleeding, including a prized 13th century cloister and a workshop for musical organs. The statement also said the archdiocese has already overhauled its financial practices to make them “more in service to its gospel mission.”

For the rest of us, here’s the interesting part of the story.

The financial woes in Maribor have developed over decades, but the Vatican apparently got wind of them only recently. In November 2009 Pope Benedict XVI appointed a new coadjutor bishop to clean house, and in 2010 the Vatican dispatched a financial expert to study the books. The obvious question is why it took the Vatican so long to get up to speed.

The answer, according to the L’Espresso report, is that the archbishop’s financial adviser pulled an end-run around rules requiring Vatican approval for debt above a certain threshold. Businessman Mirko Krasovec reportedly said that he didn’t consult Rome because he thought the requirement only applied to individual loans, not to cumulative debt, and that they applied only to the archdiocese itself, not to companies owned by it or affiliated with it.

L’Espresso offered this bit of speculation: In the wake of the Maribor meltdown, the Vatican may consider “more stringent controls on bishops and priests who fancy themselves latter-day J.P. Morgans.”

Ecclesiologists, of course, might wince at that idea. There’s a solid argument to be made, rooted in the principle of subsidiarity, for the Vatican to defer to local bishops on administrative questions which are not matters of faith or morals, even if bishops sometimes abuse that latitude.

Yet L’Espresso may be right that the Vatican will consider more exacting financial controls, for three reasons.

First, in a 21st century world, the notion of a purely local scandal is an anachronism. No matter how isolated a corner of the planet, if a problem breaks out in the Catholic church, it metastasizes on the Internet and quickly becomes a “Vatican story,” if only through the lens of “Why hasn’t Rome done something?”

Second, the Vatican is reeling from its own financial headaches, including accusations of corruption at the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples under its former prefect, Cardinal Crescenzio Sepe, and an investigation of the Vatican Bank for alleged violations of anti-money laundering statutes. Partly in response, Pope Benedict recently created a new financial watchdog agency in the Vatican. The climate is primed, in other words, for a comprehensive review of money management.

Third, the sexual abuse crisis has already created a sense that Rome needs to take a more direct hand in overseeing local bishops, to remedy a perceived lack of accountability. It wouldn’t be much of a stretch to extend that vigilance to financial questions.

Yet even if the Vatican doesn’t act, the Maribor episode likely will accelerate momentum at other levels of the church towards “good government.” It will make bishops and other church leaders more wary about trusting financial Svengalis, and it hands reformers another card to play in making the case for best practices, such as outside audits and professional investment strategies.

Another force pushing the church in that direction is the rise of the global south in Catholicism. Across Africa, Asia and Latin America, the struggle against corruption in politics and business is a defining social justice priority, and it will be difficult to make that case if the church is not perceived to have clean hands itself.

It’s a root sociological principle that scandal breeds reform, and in that sense, the Maribor story is likely to have relevance well beyond the Alps.

* * *

On Jan. 21, the Supreme Court of India delivered its long-awaited verdict upholding a life sentence for a radical Hindu activist in the murder of Graham Staines, an Australian Evangelical missionary burned to death along with his two young sons in 1999. The Supreme Court rejected the death penalty for activist Dara Singh, which under Indian law applies only in the “rarest of rare” cases.

The verdict was welcomed by the Catholic bishops of India, both because someone was held accountable for anti-Christian violence stemming from Hindu radicalism, and because the death penalty was not applied.

Yet the bishops were also critical of the reasoning in the Supreme Court ruling, which seemed to suggest that the intent behind the crime somehow lessened its gravity. That intent, according to the justices, was “to teach a lesson to Staines about his religious activities, namely, converting poor tribals to Christianity.”

The ruling repeatedly expresses disapproval of missionary activity, especially among members of the tribal groups, meaning the roughly 85 million indigenous persons in India who occupy the lowest rungs of the socio-economic ladder. They account for a disproportionate share of recent converts to Christianity, including the Catholic church, whose membership is heavily drawn from the “Dalit” underclass. Hindu radicals accuse Christians of coercing, even forcing, Tribals and Dalits into conversion, a suggestion which the Supreme Court ruling could be read to support.

The fear, in other words, is that the ruling may do as much to stoke anti-Christian hysteria as to retard it.

“I am deeply concerned about the implications of this judgment,” said Cardinal Oswald Gracias of Mumbai, speaking on behalf of the Indian bishops.

“Religious freedom is a human right,” Gracias said, “just as it’s a human right for a person to present his own beliefs to others, and it is a human right for every person to freely accept a religious practice and beliefs.”

In terms of broad implications, here’s the take-away.

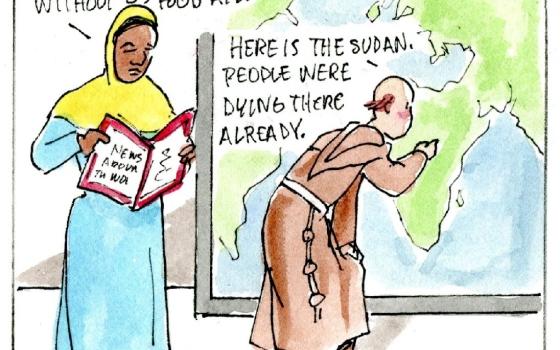

As the 21st century rolls on, the leadership tone in Catholicism will increasingly be set by guys such as Gracias, who live in neighborhoods where the battle for religious freedom isn’t about an alleged “war on Christmas” or the latest exhibit in an art gallery. It’s a matter of life and death, as recent events in Iraq, Egypt and Nigeria, as well as India, eloquently illustrate.

As leaders from those parts of the world exercise greater influence on the Vatican and on global Catholic consciousness, religious freedom will be set in stone as the church’s top diplomatic and geopolitical priority.

In English-speaking Catholicism, India in particular will be a force. By mid-century there will be 25 million Catholics in India, more than the Catholic populations of England, Ireland and Canada combined. Since English is the primary language of Indian theological and public policy debate, Indian Catholics will exercise a gravitational pull in Anglophone Catholic circles.

The pride of place assigned to religious freedom may frustrate some Catholic social justice activists, who would like to see a greater share of time and treasure invested in anti-poverty crusades, campaigns against war and the arms trade, environmental struggles, and so on. Those issues won’t disappear, but as long as Catholics have to fear for their lives precisely in those parts of the world where the church is experiencing its most dramatic growth, defending religious freedom will remain at the top of the to-do list.

* * *

As a footnote on India, senior officials from the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, led by American Cardinal William Levada, traveled to Bangalore for an unusual colloquium involving the Indian bishops and a cross-section of 26 Indian Catholic theologians Jan. 16-22.

Indians have pioneered some of the most daring theology in the Catholic world over recent decades in the area of religious pluralism, meaning the relationship between Christianity and other religions. Though the colloquium took place behind closed doors, reports from the UCAN news service suggest there was a lively exchange, pivoting on the tension between respecting the core doctrines of the faith (especially Christ as the lone and unique Saviour of the world) and the cultural context in which those doctrines have to be proclaimed.

The fact that the Vatican’s doctrinal brain trust flew halfway around the world to have that conversation is another way of saying, “India matters.”

It’s also worth noting that Maltese Msgr. Charles Scicluna, the Promoter of Justice in the CDF and in effect the Vatican’s chief prosecutor on sex abuse cases, was part of Levada’s delegation. That’s significant because India has been a focal point for frustrations about disparate policies on sex abuse around the Catholic world, including perceptions that foreign-born priests facing accusations in the United States or Europe can simply return home and evade justice.

Last April, the case of Fr. Joseph Palanivel Jeyapaul stirred headlines. Jeyapaul had served in the Crookston diocese in Minnesota during 2004-05, and was later accused of sexually assaulting two minor girls. In the meantime Jeyapaul had returned to his home diocese in southern India, where he continued serving as a priest in a bureaucratic capacity even after his bishop had been informed of the charges. The bishop imposed “precautionary measures” but not removal from ministry, which is the policy in the States.

It will be interesting to track whether Scicluna’s visit leads to greater coordination of sex abuse cases among the Indian bishops and the nations to which their clergy are being dispatched these days.

* * *

Finally, I filed a story this week for the print edition of NCR updating the relationship between the U.S. bishops and the Catholic Health Association, representing more than 1200 Catholic hospitals, health systems, and other healthcare facilities in America.

The story does not focus on the strains in that relationship, which would be a sort of “dog bites man” reporting. Everybody knows what the tensions are: fallout over the national debate over healthcare reform, and the more recent case in Phoenix in which Bishop Thomas Olmsted revoked the Catholic status of a member hospital over accusations that it performed an indirect abortion. While the CHA has accepted Olmsted’s authority to do that, it clearly doesn’t share his conclusion.

Instead, I concentrated on the more surprising dimension of the story: To wit, despite all the headaches, the two sides are still talking. In fact, I quoted four leading American bishops, including the past and current presidents of the bishops’ conference, to the effect that their ties with the CHA remain fundamentally strong, and that good conversations are taking place.

The two key players in that dialogue now are Archbishop Timothy Dolan of New York, president of the bishops’ conference, and Daughters of Charity Sr. Carol Keehan, president of the CHA.

Here’s why the story is relevant beyond its immediate implications for Catholic healthcare.

It’s a notorious fact of life that American Catholicism is often a house divided against itself. Though it’s hardly the only one, a primary fault line these days runs between the evangelical wing of the church and its reform-minded, social justice-oriented camp. What makes the CHA story beguiling is that in many ways, Dolan and Keehan are apt symbols for that larger contrast.

Dolan is a quintessential evangelical Catholic, a self-described “John Paul II’ bishop -- robustly orthodox, far more interested in taking the church’s message to the streets than in tinkering with its internal structures, and proud of the way the American bishops have made the pro-life cause their defining social concern. Dolan’s election to the presidency of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops marks, as writer George Weigel argues in a recent First Things essay, “the End of the Bernardin Era” -- a reference to the late Cardinal Joseph Bernardin of Chicago and his center-left leadership.

Keehan, of course, is an American woman religious representing one of the primary carriers of the church’s social mission. She’s unapologetically pro-life, but sees that commitment as part of a continuum of concerns about human life and dignity -- a core element of the Bernardin vision.

Yet neither Dolan nor Keehan are in any sense extremists, and both insist that what unites them is more fundamental than their differences.

Keehan is willing to pay the price of admission for any serious effort to engage officialdom, which is a clear acknowledgment, as Olmsted put it in his letter to the Phoenix hospital, that “there cannot be a tie” in the Catholic system; ultimately, it’s up to the bishop to decide. Dolan, for his part, clearly understands that for episcopal authority to be credible, it has to be exercised with restraint and only after wide consultation.

(In a recent interview, Dolan said he’s well aware that for many people these days, in the wake of the sex abuse crisis, listening to the bishops speak about morality is like “Nixon giving a talk on clean government.” He said bishops have to defend “the unique normative value” of their magisterium, but they have to do it with “graciousness” and even “a sense of contrition” for past failures.)

My point is this: If Dolan and Keehan, and the bishops and Catholic healthcare providers they represent, can stick together, it would provide a powerful lesson for the rest of the church that our internal tensions do not have to be fatal.

There are, naturally, plenty of people who would love to see Dolan and Keehan at one another’s throats, and those are usually the loudest voices in the room. Perhaps it’s time for the quiet middle in the church to let them know that sanity has a constituency too.