The Maiduguri Diocese camp for internally displaced persons houses about 500 Catholics who are sheltering from persecution by Boko Haram militants. It is on the site proposed for the diocese's secretariat. (Festus Iyorah)

Every Monday through Saturday at the camp for internally displaced Catholics in the Jiddari Polo neighborhood of Maiduguri, the largest city in northeastern Nigeria, Catherine Ibrahim and her two children gather alongside a group of Catholics to pray the holy rosary in their Hausa dialect.

At 6 p.m., the prayers start with kneelers kissing the floor, hands clutched to rosaries of different colors and sizes, heads bowed and voices raised in unison. The prayers end with praise and worship chorused in a joyous mood that transcends their predicament.

After the prayers, the Catholics exchange pleasantries deeply woven in camaraderie. But behind the warmth are sad tales of a people broken and crushed by the Boko Haram Islamist sect, responsible for killing 20,000 people and displacing over two million. Boko Haram, literally translated to "Western education is forbidden," has also left about 5 million people food insecure.

Life was good for Ibrahim and her family in the rocky town of Gwoza, southeast of Maiduguri — home to minority Christians in a majority Muslim state. Ibrahim and her husband planted maize and groundnut (a kind of peanut) to earn a living.

In December 2012, Ibrahim's source of livelihood crumbled when Boko Haram insurgents overran her parish in the hilly town of Lagara, near Gwoza, during Sunday Mass.

They started shooting and everyone was running back and forth, she remembers.

"They came with guns on their backs," she said, patting her back to explain. They shot at everyone, the catechists, the church council chairman, everyone. They burned down houses, including the church, she said.

When the chaos subsided, Ibrahim trekked with her two children and husband from Lagara to Pulka, a neighboring town, to seek refuge. But their stay was short-lived with yet another attack. This time, Ibrahim lost her husband. He was shot while running alongside Ibrahim and their two children trying to escape the terror. She watched as the bullet pierced his neck, killing him instantly.

"I was just crying. I hid under tree with my children. We couldn't move because of stray bullets flying everywhere," Ibrahim told NCR.

Ibrahim braved the sporadic gunfire and crawled out of the danger zone with her children, avoiding being seen by the insurgents. The family trekked to Ngoshe, another town in the Gwoza region.

Then, in 2013, her children — Daniel, age 9, and Salome, age 12, were kidnapped. Ibrahim had gone to fetch water alone when she heard gunshots. When she got back she was greeted with dead bodies. Her children were abducted.

"They killed all the men and kidnapped children and women at Ngoshe. I saw dead bodies scattered everywhere, nobody buried them," she said.

Every Monday through Saturday at the camp for internally displaced persons in Maiduguri, Catholics gather to pray the rosary. (Festus Iyorah)

Inside Boko Haram's caliphate

In 2012, during the peak of its attacks, Boko Haram — named a terrorist organization by the United States in 2013 — captured towns in northeast Nigeria, establishing an Islamic caliphate. Gwoza, almost the size of Rhode Island, was on the verge of being captured, and Ibrahim did not want to live under the authority of jihadists who gained notoriety for using women and girls as suicide bombers. Instead, from Ngoshe, she walked barefoot for three days and nights, braving the cold, to the neighboring state of Adamawa, which had yet to be captured by the insurgents.

"For the three days I trekked alone, I was always praying the rosary in my heart," she said.

She remained in Adamawa for months; her children were still with the insurgents who had turned Gwoza into the capital of their Islamic caliphate.

"I couldn't eat. I was about to die, they killed my husband and kidnapped my two children," she said.

In the winter of 2014, Ibrahim decided to travel back to Gwoza along the road to look for her children.

In Boko Haram's version of Islamic caliphate, shariah is enforced, a legal system that compels people to live by the precincts of Islamic laws. Anyone who lives outside this law is considered an infidel. This is the kind of "utopia" Muhammed Yusuf envisioned when he started preaching his version of jihad against the Nigerian state in 2002.

Nigeria's long years of maladministration and the high rate of poverty in the northern part of the country — the birthplace of the insurgents — galvanized them into taking up arms. Subsequently, the sect started killing and maiming innocent citizens.

The group's ideology claims to be against the constituted government of the country but has morphed into the establishment of Islamic order, writes Abdul Gafar Olawale, a scholar at the University of Ilorin in north central Nigeria.

Huge humanitarian crisis

Ibrahim's plan to save her children didn't pan out well. When Boko Haram fighters found her alongside another woman also trying to save her children, they were arrested and detained. With hands tied behind their backs, the women were beaten and maltreated for 20 days — without food. The other woman did not survive the torture and died in custody.

"In order to survive, I played dead so the insurgents will dump my body by the roadside as they did with other bodies. That was where the Nigeria army found and rescued me," she told NCR.

In 2015, Ibrahim was transferred to the care of the Maiduguri Diocese where she received treatment for her bruises and fractured hand. She was then relocated to the Catholic camp for the displaced faithful.

The camp — which accommodates about 500 Catholics (300 families) — is the only source of survival for Catholic internally displaced persons. Families displaced by the insurgency are provided with a room or a makeshift tent in the camp — originally the proposed site for the diocese's secretariat. The church also provides free education for displaced children and free medical services.

Catherine Ibrahim, 44 (Festus Iyorah)

With little or no support from the government, the Maiduguri Diocese has spent over 150 million naira (US $416,000) on displaced persons, using its own funds and donations from dioceses across Nigeria.

The diocese has also received help from other organizations, including MISSIO, the Catholic Church's official charity for overseas missions. The German-based Catholic charity Aid to the Church in Need provided a grant of $75,000 for 5,000 widows and 15,000 orphans under the care of the diocese; and Catholic Relief Services provides school uniforms, textbooks and school fees for about 100 Catholic children.

In the summer of 2015, the Nigerian Army recaptured Gwoza. Many citizens, including Ibrahim's two children were released and transferred to Maiduguri.

"I was excited to see my children but I was also surprised they had learned how to read the Quran by heart," she said. She asked them to recite the Quran, hoping they'd have forgotten it. But they recited a verse of the Quran fluently.

Ibrahim's ordeal in the hands of the Islamic insurgents is evident. She is 44, but looks much older. Her arms and legs are covered in dark brown welts — signs of being beaten by Boko Haram. She wobbles when she walks, and her left hand, fractured after being bound for 20 days, occasionally goes numb.

"I can't do anything with this left hand. I can't grip something for long with it," she told NCR.

Advertisement

Maiduguri martyrs

Ibrahim and other survivors, who share similar stories of pain, suffering and loss, mirror the challenges the Catholic Church in the northeast region of Nigeria is facing.

Since Boko Haram launched its first attack in the summer of 2009, the church has been deeply affected by the conflicts.

The Maiduguri Diocese comprises the whole of Borno state, Yobe and some part of Adamawa — all in northeast Nigeria. It is the largest in terms of land mass. But in terms of population, the diocese has about 300,000 Catholics, according to Fr. John Bakeni, diocese secretary.

More than 100,000 Catholics, 200 catechists, 26 priests and 30 nuns have been displaced, and more than 200 parishes, especially in the northern part of Adamawa and northern Borno, have been destroyed. The diocese also lost 17 schools, six clinics and four convents. The insurgents have killed at least 5,000 Catholics and destroyed 22 rectories, according to the diocese. But attacks against the Catholic Church and Christians in northern Nigeria were happening years before Boko Haram.

"People try to place the historical timeline that it started in 2009 but we have been experiencing torture," Bakeni said. "On Feb. 18, 2006, for instance, one of us, Fr. Michael Dagere, was killed. He was murdered in cold blood in his parish by some Muslim hoodlums. We had another incident where the bishop's house was burned."

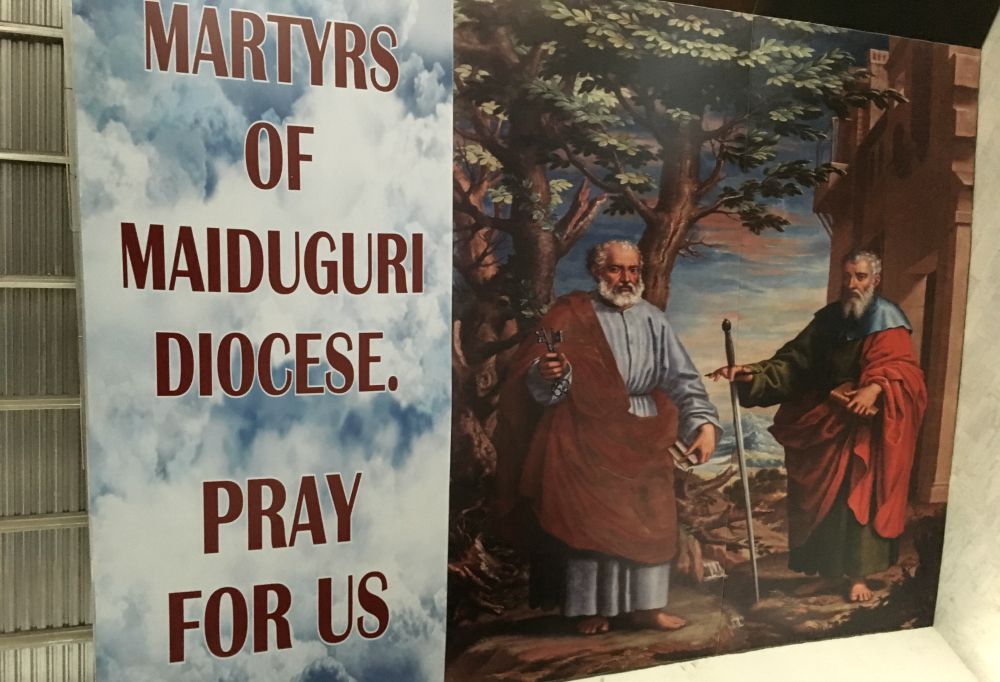

The Maiduguri Diocese calls the victims of Boko Haram martyrs. In 2017, after completion of a new cathedral, St. Patrick, located in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno, a big banner inscribed with "Maiduguri martyrs pray for us," hangs on the left wing of the altar.

This was deliberate, said Bakeni. "The Maiduguri Diocese is a suffering church. It's a persecuted church, so after we built the church we kept the banner there."

"In fact, all I can say is that the faith [of Catholics in this region] has been tested and proven. What we are going through here is for the purification of the mother church. It is in such a moment that the church is defined," Bakeni adds.

Banner that hangs to the left of the altar of St. Patrick Cathedral in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state in Nigeria (Festus Iyorah)

St. Patrick Cathedral in Maiduguri, completed and dedicated in 2017 (Festus Iyorah)

Widespread persecution

Nigeria's population is comprised of 49 percent Christians in the southern region and 48 percent Muslims in the north, according to Pew Research Center. The north is a conservative Islamic region, where attacks against the church — especially during Mass — became more pronounced after 2009.

On Dec. 25, 2011, Boko Haram planted a bomb at St. Theresa's Catholic Church in Nigeria's capital of Abuja. In what looked like a coordinated attack against Christians, about 30 parishioners were killed and about 50 people were injured; 10 others were killed the same day in other churches across four northern cities. Bombs continued in 2012 with two explosions that killed about 20 people and wounded about 140 in Kings Catholic Church in Zaria and St. Rita's Catholic Church in Malali — both in northwestern Kaduna state.

There have been occasions where angry Christian youths retaliated against the attacks by killing Muslims, prompting a sectarian crisis in a region where thousands are divided along ethnic and religious lines.

The Nigerian government says the insurgents have been defeated, but the war seems far from over. Apart from the abduction of the Chibok girls that sparked global outrage in 2014, about 110 girls were kidnapped in February from their high school dormitory in northeast Nigeria. After negotiations, the girls were released except for Leah Sharibu, who refused to renounce her Christian faith.

Nigeria President Muhammed Buhari, the first Nigerian to defeat an incumbent in a presidential election, came to power in 2015 with a promise to defeat the Islamist sect, but insurgents still carry out abductions and attacks. Under Buhari's watch, new security threats, like killings between Christian farmers and Muslim pastoralists, have increased. The president has been widely criticized by citizens, Christian leaders and the Nigerian Catholic Bishops' Conference. In February, U.S President Donald Trump also called for the violence against Christians in Nigeria to stop when he welcomed Buhari to Washington.

Back in the camp, Ibrahim and other survivors are undeterred. Instead, they are thankful and firm in their faith. Most of them are part of the local choir, Legion of Mary, and other Catholic societies and organizations.

"No matter the suffering, I can't turn away from God because he saved me when I thought I'd not make it," Ibrahim said.

[Festus Iyorah is a freelance journalist based in Lagos, Nigeria.]