Pope Francis greets people at the "Regional Hub," a government-run processing center for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, in Bologna, Italy, Oct. 1, 2017. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano)

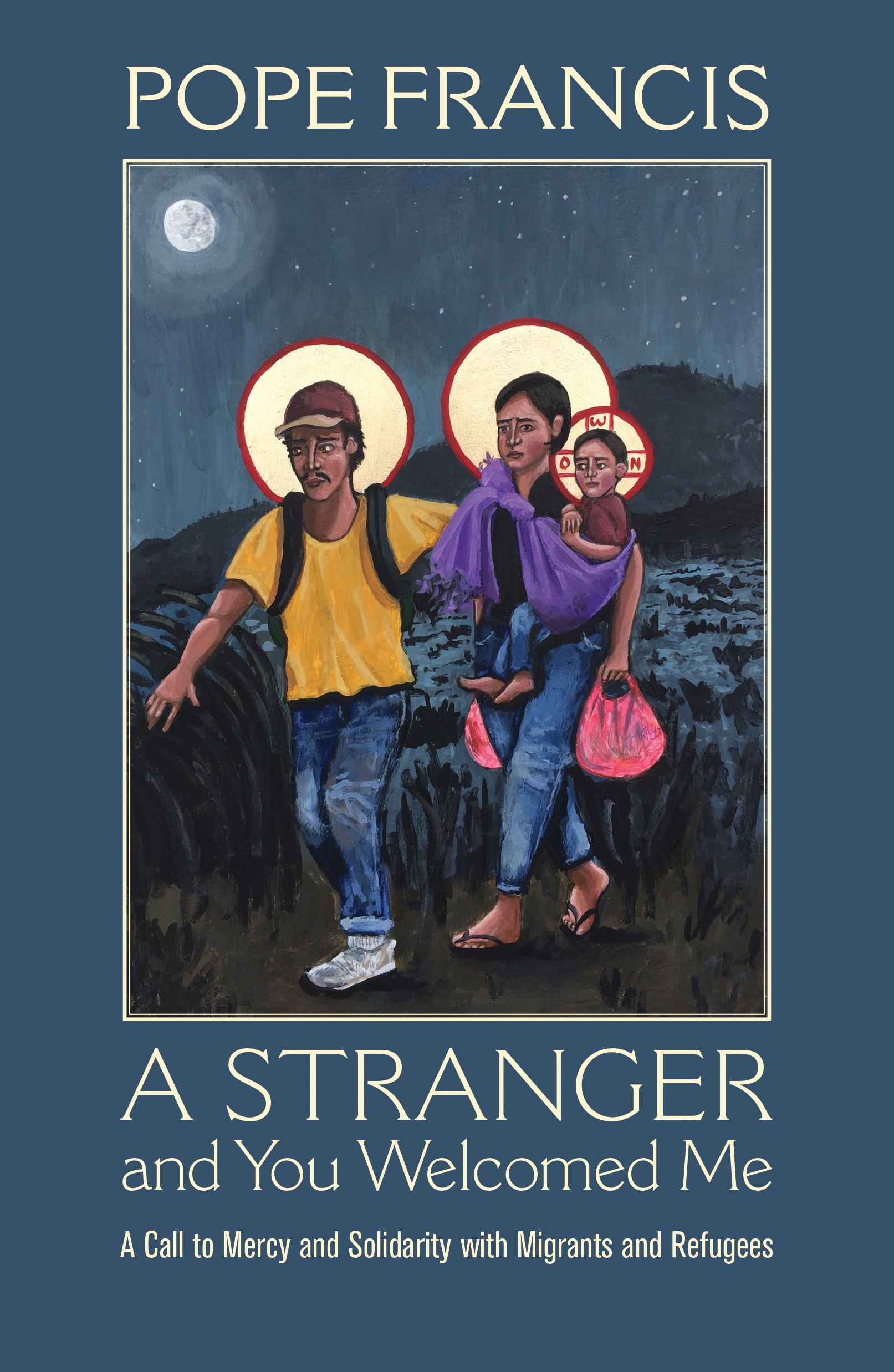

Editor's note: This excerpt has been adapted from the introduction to A Stranger and You Welcomed Me: A Call to Mercy and Solidarity with Migrants and Refugees, edited by Robert Ellsberg.

Pope Francis established his concern for the plight of migrants and refugees on his very first trip outside of Rome, just months after his election as pope. On the Italian island of Lampedusa, a waystation for many refugees making their way to Europe, he celebrated Mass and commemorated the thousands who have died at sea. Their fate, he said, confronts us with the same question that God put to Cain: "Where is your brother?"

It was an occasion for the pope to introduce one of his signature concerns: the "globalization of indifference" that makes it difficult for us even to recognize our brothers and sisters. "The culture of comfort, which makes us think only of ourselves, makes us insensitive to the cries of other people, makes us live in soap bubbles which, however lovely, are insubstantial. … We have become used to the suffering of others: It doesn't affect me; it doesn't concern me; it's none of my business!"

And so for the pope, the issue is not only the plight of defenseless people, forced to contend with heartless traffickers and the perils of a journey that has made of the Mediterranean Sea "a vast cemetery," and whose blood cries out to God. It is fundamentally a question that God puts to the rest of us, especially Christians: Where are we? Who are we? The tears of migrants and refugees find a damning counterpart in our own lack of tears: "Has any one of us wept because of this situation and others like it? … Today has anyone wept in our world?"

That is a question that underlies the homilies, speeches, prayers and documents collected in this volume. The pope does not offer colorful stories or memorable anecdotes. He does not assemble facts or statistics, nor does he set out to propose specific policies or measures for reform. His aim is to awaken a spirit of mercy and solidarity, in hopes that such a spirit will inspire whatever response we make — whether as individuals, as communities, or as nations. He proposes, in essence, a single simple message repeated in a hundred different ways: Migrants and refugees are human beings, precious in the eyes of God; they are our brothers and sisters; they are worthy of respect; what we do for them, we do directly for Christ.

Does such a simple message require a whole book? One might as well ask Francis why he finds it necessary to repeat this message on so many occasions and in so many ways. Over and over, he returns to this theme, whether visiting refugee camps in the Middle East, or preaching at the Mexican border town of Ciudad Juárez, or speaking to a joint session of the U.S. Congress.

Repeatedly, he anchors his concern in simple texts from Scripture: the repeated commandment to "welcome the stranger" and the reminder that "you yourselves were strangers in the land of Egypt" (Exodus 22:21); the words of Jesus, "I was a stranger and you welcomed me" (Matthew 25:36); and above all, the reminder that the Holy Family themselves, in their flight into Egypt, shared the experience of contemporary refugees. Clearly, for Francis, our response to the challenge posed by migrants and refugees is not simply another political or economic problem, but a profound test of Christian faith.

Directing his words to a global audience, the pope has not generally addressed specific debates in the United States. (A notable exception occurred during an in-flight exchange with reporters in 2016, when he was asked about candidate Donald Trump's promise to build a wall on the Mexican border: "A person who thinks only about building walls, wherever they may be, and not building bridges, is not Christian. This is not the Gospel.") Nevertheless, if the pope regards the issue of migrants and refugees as a defining item in his agenda, he has apparently found his opposite counterpart in the current president of the United States.

Advertisement

Donald J. Trump literally inaugurated his presidential campaign in June 2015 with a press conference in Trump Tower in which he assailed the impact of Mexican immigrants: "When Mexico sends its people, they're not sending their best. They're not sending you. … They're bringing drugs. They're bringing crime. They're rapists. And some, I assume, are good people."

The supposed dangers posed by "illegal aliens" inspired the promise of his campaign mantra to "build the wall." He has consistently blurred the lines between immigrants in general and violent gang members whom he delights in calling "animals."

Most controversially, treating all immigrants, including those who formally apply for asylum, as criminals, his administration implemented a policy of separating children — even infants and toddlers — from their parents, when they were apprehended at the border. In the face of widespread protest, this policy was supposedly rescinded, but attendant cruelties continue. Meanwhile, the administration has successfully reduced the admission of refugees to the United States by over 70 percent.

In his speech to Congress in 2015 — long before this issue had reached a boiling point — Pope Francis spoke of America as a land of dreams, "dreams which awaken what is deepest and truest in the life of a people." He spoke specifically of the "millions of people who came to this land to pursue their dream of building a future of freedom." As the son of immigrants, he pointed out that so many of those in his audience (if not all of them), were also descended from immigrants. "For those peoples and their nations," he said, "I wish to reaffirm my highest esteem and appreciation." While acknowledging that many of these immigrants encountered hostility and violent opposition, nonetheless, he insisted, "when the stranger in our midst appeals to us, we must not repeat the sins and the errors of the past. … Building a nation calls us to recognize that we must constantly relate to others, rejecting a mindset of hostility in order to adopt one of reciprocal subsidiarity, in a constant effort to do our best. I am confident that we can do this."

Pope Francis poses with migrants during his general audience in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican June 6. (CNS/Paul Haring)

From a distance of three years, the pope's confidence in the capacity of Americans to embrace the better angels of their history may seem blissfully naive. With each passing week, official policies and accompanying rhetoric seem to set new standards in heartlessness and division, as if explicit denial of the pope's call for mercy and solidarity were the prerequisite for Making America Great Again.

Who knows whether any hearts and minds will be changed by the pope's oft-repeated message? Nevertheless, he urges us to consider that it is not only migrants and refugees who are the victims of our hardheartedness. Those of us who turn a blind eye, who tell ourselves, "It doesn't concern me; it's none of my business!", are also the losers.

As he notes, "The poor are also the privileged teachers of our knowledge of God; their frailty and simplicity unmask our selfishness, our false security, our claim to be self-sufficient. The poor guide us to experience God's closeness and tenderness, to receive his love in our life, his mercy as the Father who cares for us, for all of us, with discretion and with patient trust."

The title of this volume, A Stranger and You Welcomed Me, is taken from Jesus' reminder that it is he who walks among us in the form of the poor and needy. "I was hungry and you fed me; I was thirsty, and you gave me a drink; I was a stranger and you welcomed me. … Insofar as you did these things for the least of my brothers and sisters, you did them for me." Our very salvation is tied to this test. But it is the following verse, and the fate of those who fall short, that should resound in our ears: "Insofar as you failed to do these things for one of these, however humble, you did not do them for me."

If, in this "culture of comfort," we have lost our bearings, it may be the stranger among us who is calling us home.

[Robert Ellsberg is editor-in-chief and publisher of Orbis Books.]