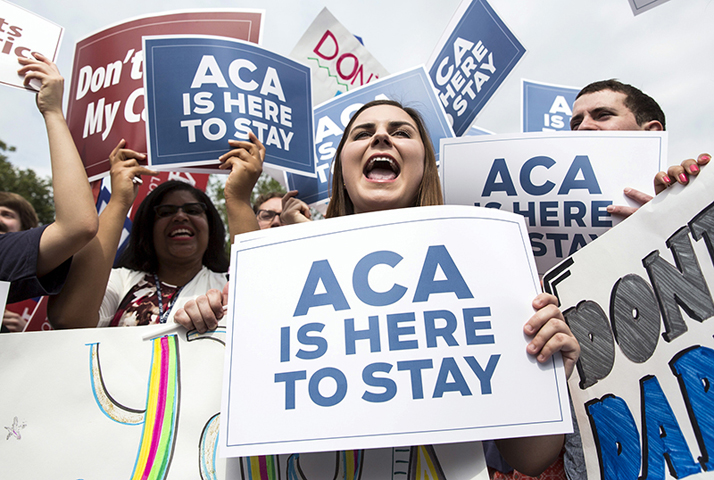

Supporters of the Affordable Care Act celebrate after the Supreme Court up held the law in the 6-3 vote at the Supreme Court in Washington on June 25, 2015. (Reuters/Joshua Roberts)

On Wednesday, March 23, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear a case about the application of the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate to religious nonprofit organizations. The case could have a significant impact on religious liberty law, far beyond what the case means for the objecting religious employers and those whose benefits will be affected.

Specifically, the court has the opportunity to clarify and hold high, or muddle and further erode, the role of religious exemptions in our religious liberty legal tradition. The court should protect religious liberty by ruling against these religious claims.

The number and variety of parties and claims make this case complex, but the underlying conflict and effort to resolve it are easily understood. Consistent with the ACA’s emphasis on preventive health care and equality, regulations require most employers to provide employees access to a full range of contraceptives at no cost.

With knowledge of religious objections to contraceptives, and particularly those viewed as abortifacients, the government developed a regulatory system with religious liberty and health care in mind.

First, churches and their integrated auxiliaries were exempted from the mandate. Second, religiously affiliated nonprofit entities (a much larger set of employers) were given a means to avoid providing contraceptives. It requires the employers’ secular insurance companies to provide the coverage separate from the employer’s plan. The regulatory road may have been long and winding, but the system is sound.

In Zubik v. Burwell (the name under which several cases, including the Little Sisters of the Poor, are consolidated), a few dozen religious nonprofit employers argue that even the exemption system violates their religious freedom. In short, the litigants say they cannot in good conscience provide contraceptives, and they likewise object to the government’s alternative for providing them. These religious employers make far-reaching arguments against the exemption designed for them. In doing so, they threaten to take religious freedom law down with it.

The employers’ claims rely on the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act, a federal law that has long enjoyed broad, bipartisan support. Unlike the specific administrative exemptions provided for churches and the religious nonprofits in this case, RFRA provides a general standard that protects religious freedom through a balancing test that weighs substantial burdens on religion against compelling interests of the government, without regard to any particular federal law or religious practice. Both specific exemptions (like the ones provided in the contraceptive mandate) and the standard in RFRA are essential to religious liberty.

As explained in a brief filed by the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty and professor Douglas Laycock, the Zubik claims go too far. Indeed, they threaten the whole enterprise of religious exemptions.

First, these employers argue that courts must give absolute deference to their claims of "substantial burden." The employers have been relieved of the obligation to pay or contract for the services. They describe the burden on their exercise of religion in various ways to object to the government’s regulation of the insurance companies with which they do business.

While courts should defer to religious claims of burden -- and complicity in contraceptives can be a religious burden -- whether it is a substantial burden under the terms of RFRA or too attenuated must be a matter of law for courts to decide. Total deference ignores the statutory scheme and changes RFRA, which invites its demise.

Second, the religious nonprofit employers make a more direct and potentially devastating attack on specific religious exemptions. They argue the mandate’s exemption system is too narrow because these employers are not treated exactly like churches. At the same time, they argue it is too broad because if the government does not cover church employees it must not have a compelling interest in coverage. Government efforts to craft religious exemptions to protect religious liberty, while also protecting other important governmental interests, should be encouraged, not discouraged with such “all or nothing” exemption claims.

The Baptist Joint Committee and Laycock have worked for more than 25 years -- often together -- to advance religious liberty and to enact, implement and defend the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. It is unusual, to say the least, for us to file for the government in a free exercise case. Religious liberty is often threatened by government indifference or oversight. As this case demonstrates, it can also be endangered by exaggerated claims and overreaching.

[Holly Hollman is general counsel for the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty.]