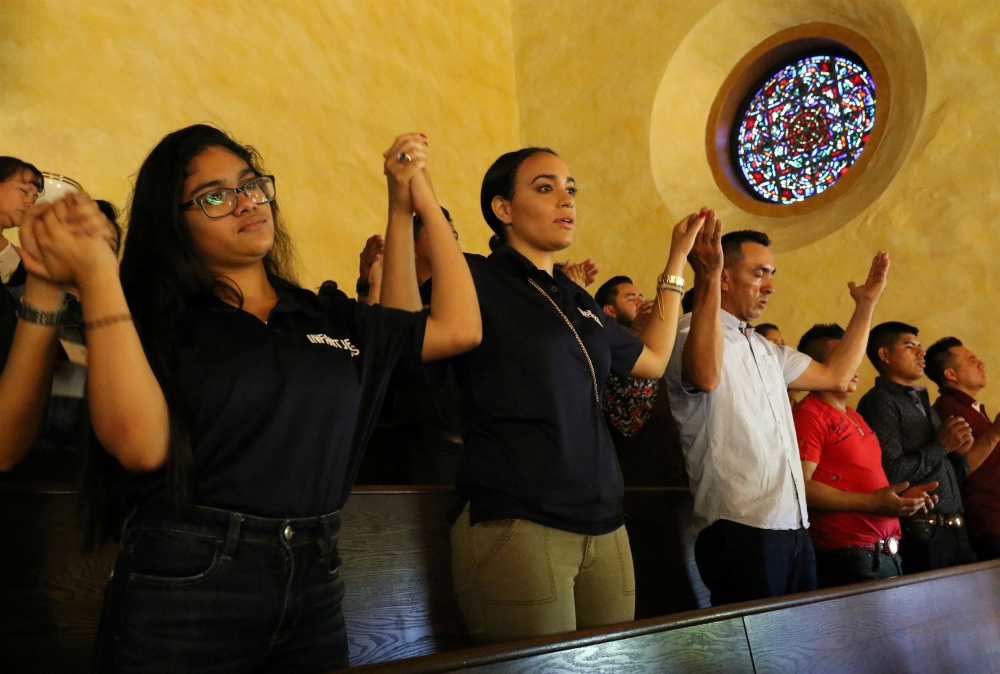

Participants recite the Lord's Prayer during Mass at the Labor Day Encuentro gathering at Immaculate Conception Seminary in Huntington, New York, Sept. 3, 2018. (CNS/Long Island Catholic/Gregory A. Shemitz)

For Catholics, it has been obvious for many years that the future of our church in the United States is a Latino future. We were ahead of the curve, and now the national political media is catching up, waking to the fact that, as one headline at Politico put it, "All Paths to 270 [electoral votes] Lead Through the Latino Electorate."

The question remains: For all the recent attention on Latinos, does anyone have a real sense of how they might affect the race?

At The Atlantic, Derek Thompson looks at the various reasons Donald Trump might be underperforming among Latino voters. He notes the emergence of a gender gap among Latinos under the age of 50, as Latino men break evenly for Trump while Biden earns 70% among Latinas. Thompson also notes that Miami-based Cubans are more supportive of Trump than they were of Romney, in part because of the rise to prominence of self-described socialists within the Democratic Party and Trump's continual effort to tar the entire party with that ideological label.

Thompson offers a caveat and a bit of sound advice:

There is no such thing as a singular Latino electorate. There are only Latino electorates, which vary by state, gender, generation, economic status, and their family's nation of origin. The challenge for Biden and future Democrats is to find a message that cuts across identities. The right approach in this election is to focus on the intersection of health and economics — and, in particular, on work.

Unfortunately, the high achievers who tend to run campaigns do not usually think about work as a central concern of voters. During this week's mourning for Ruth Bader Ginsburg, how many Democrats publicly worried about losing a pro-labor vote compared to the avalanche of concern that Roe v. Wade might be overturned?

And one issue that is missing from Thompson's look at Latinos? Religion.

An interview at Politico with Stephanie Valencia, a co-founder of Equis Research, which specializes in polling and research about Latinos echoed some of these points.

Valencia worked in the Obama administration, and her firm does work for Democratic candidates. She made the point that you have to look at each state individually, because the make-up of the Latino population varies widely, with Mexicans and Central Americans dominant in the Southwest, and Cubans and Puerto Ricans predominant in Florida and the Northeast.

Even that breakdown is too facile in a state like Florida. "We tend to look at Latino voters in Florida in a very binary way: If we're not talking about Cubans, then we're talking about Puerto Ricans," Valencia said. "But only a third of the Latino electorate in Florida is actually Cuban-American — it's very important, but it is only a third. More than one-third is actually not Cuban or Puerto Rican. They're Mexican. They're Colombian. They're Peruvian. They're Ecuadorian. Combined with the Puerto Rican community, they're much more similar to each other than not."

Advertisement

This tracks with my own experience. Both in the D.C. area and now in northeastern Connecticut, the Latino population is changing and more varied than the single word "Latino" suggests. In D.C. in the 1980s, most of the immigrants were from El Salvador and Nicaragua, but by the time the new century rolled in, other Central Americans and Mexicans had begun filling our churches. In Connecticut, there has been a strong Puerto Rican presence since the 1950s, but now it is augmented by Dominicans, Peruvians and Mexicans.

Beyond the issues of different nations of origin, Valencia agreed that Latinos have a variety of political concerns beyond immigration, and this is an opportunity for Joe Biden. "Joe Biden, it's no secret, didn't win the Latino vote in the primary," she said in the Politico interview.

"There were some unique issues that Bernie Sanders was able to tap into that really related to the everyday lives of Latinos in this country, including universal access to quality health care, free community college and getting advanced degrees without acquiring a lot of debt, and immigration," she said. Although she was not ranking them, it was interesting that she listed immigration last.

The missing element in the interview? Nothing about religion.

At The New Yorker, Stephania Taladrid looked at the Latino vote and noted the importance of reaching out to young Latino voters. "Approximately forty per cent of eligible Latino voters are between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five — nearly four million of them have become eligible to vote since 2016," she wrote. "Trump is highly unpopular with the group, yet polls also show that young Latinos, in particular men, are deeply cynical about politicians."

She noted that young people also have one quality their seniors tend to lack: They are more reachable by social media. Due to the relative inability to campaign in person because of the coronavirus, that social media messaging may prove critical, not least because of the disinformation the Trump campaign and its allies are spreading in Spanish-language media that Taladrid details.

But what was missing from Taladrid's analysis? No mention of religion.

In The New York Times, Ian Haney López and Tory Gavito penned a sobering article for progressives, especially progressive academics. They noted that a majority of Latinos do not see themselves as "people of color." In fact, according to their research, "the majority [of Latinos] rejected this designation. They preferred to see Hispanics as a group integrating into the American mainstream, one not overly bound by racial constraints but instead able to get ahead through hard work."

An employee closes the gate of a Latino restaurant in New York City April 2 during the coronavirus pandemic. (CNS/Reuters/Anna Watts)

What is more, they posed some racist dog whistles about "illegal immigration from places overrun with drugs and criminal gangs" and calling for "fully funding the police, so our communities are not threatened by people who refuse to follow our laws" to focus groups. Three-fifths of all white people surveyed thought the comments were "convincing" and the same percentage of African Americans agreed. Latinos? Even more of them agreed with the statements.

López and Gavito's conclusion was that "how the [Latino] person perceived the racial identity of Latinos as a group shaped his or her receptivity to a message stoking racial division."

If the Biden team is listening to academics and activists who insist on thinking an appeal to racial identity obviates the need for an argument, they will be in for a surprise on Nov. 3.

And — you guessed it — this otherwise informative piece failed to consider the role of religion in how Latinos might vote.

A consistent theme is that very little polling asks about the religious identification of Latinos, or if it does, the sample size is so small, and consequent margin of error so large, the numbers are meaningless. The recent EWTN/RealClearPolitics poll showed Hispanic Catholics backing Biden over Trump by a margin of 63% to 31%, a much wider margin than Biden's performance among all Catholics, which came in at 53% to 41%. The poll had a margin of error of +/-3% based on 1,212 respondents. That is a better sample size than most other polls, but for Latino likely voters, the number of respondents would drop to fewer than 600.

A survey by the Texas Hispanic Policy Foundation included an oversampling of Latinos, but the sample size still seems small to me. Nonetheless, it confirmed a hunch of mine: One of the reasons Trump does relatively well among Latinos is because of the growing number of evangelical and Pentecostal Latinos. Trump led 51% to 24% with Hispanic evangelicals while Biden led 61% to 33% among Hispanic Catholics.

I hope other pollsters will test for religion when polling Latinos, and in states beyond Texas. And anyone in the campaign war rooms should be looking for an answer too: Whether it is Arizona or Nevada or Florida or even Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, Latinos may be the deciders this year and where they worship on Sunday may hold a key to how they will vote.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.