Detail of "Crucifixion," circa 1470, showing women pulling out their hair in mourning by Bertoldo di Giovanni, in bronze at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence, Italy (Menachem Wecker)

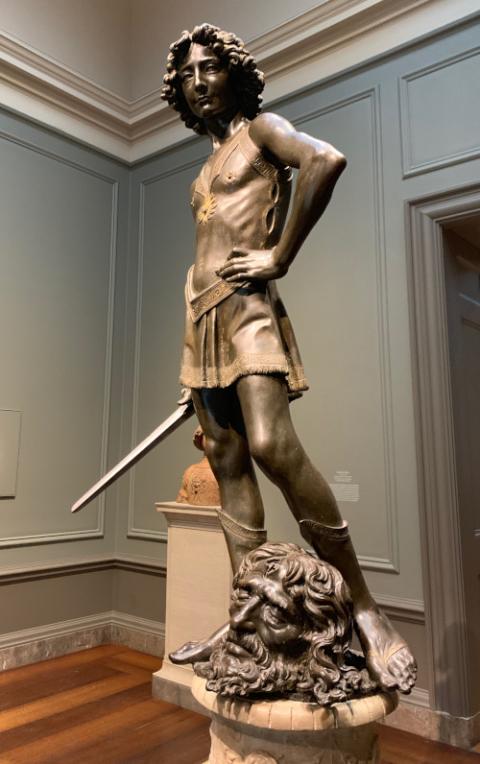

It's a tale of two stones. One, now lost, was embedded in Goliath's head, sculpted around 1465 by Florentine artist Andrea del Verrocchio (circa 1435-1488). The life-sized bronze "David with the Head of Goliath" by Verrocchio, who taught Leonardo da Vinci and perhaps Sandro Botticelli, is on view at Washington's National Gallery of Art through Jan. 12, 2020, in "Verrocchio: Sculptor and Painter of Renaissance Florence."

St. Jerome clenches the other rock in his right hand in a circa-1465-1466 painted wooden sculpture by Bertoldo di Giovanni (circa 1440-1491). Donatello probably collaborated with his student Bertoldo on the life-sized work, which appears in "Bertoldo di Giovanni: The Renaissance of Sculpture in Medici Florence" (through Jan. 12) at New York's Frick Collection. (Bertoldo taught Michelangelo and was one of Lorenzo the Magnificent's favorite artists.)

Separated by 250 miles, the sculptures and the exhibits containing them have a good deal to say to one another and collectively shed light on two lesser-known Renaissance artists, who deserve recognition outside the shadows of their illustrious students and teachers. That's particularly true of Verrocchio's and Bertoldo's religious artworks.

Bertoldo's relatively-small bronze crucifixion (from the 1470s), about 24 inches per side, captures an impressive emotional range. Cirrus clouds frame the crucified Christ and two thieves atop the work, while eight people mourn below. St. Jerome is identifiable by his rock and crucifix, while other attributes mark St. Francis and two women. Mary Magdalene, whose billowing, revealing clothing exposes her breast, has pulled out two curly clumps of her own hair, which she holds in her right hand nearly touching Jesus' feet. Her left hand is poised to rip out another bunch of hair. (A kneeling woman, perhaps another Mary, has also pulled out a clump of her own hair.)

"It's supposed to be shocking how she's showing grief," co-curator Alexander Noelle told NCR in an interview. The work, he says, offers a surrogate figure for viewers and is nothing less ambitious than a how-to guide for mourning.

Prior artists have shown grief-stricken witnesses of the crucifixion, but this degree of mourning is highly unusual. Hair tearing is consistent with biblical practices, as described, for example, in Ezra 9:3, which tells of garment rending and hair and beard plucking.

"David with the Head of Goliath," circa 1465, by Andrea del Verrocchio, in bronze with partial gilding at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence, Italy (Menachem Wecker)

The blood dripping down St. Jerome's chest (below the rock) in the nearby sculpture, upon which Bertoldo and Donatello likely collaborated, would have been viewed from below originally in a chapel niche. That would have made the blood "more legible to those looking at it from below," writes co-curator Aimee Ng in the exhibit catalog. In its original configuration, the saint seemed to have held a now-missing crucifix in his left hand, and he wore a loincloth; as he stands at the Frick, he is naked, and many of the emaciated saint's veins are rendered expertly. His expression — particularly the sunken eyes and pursed lips — evokes Donatello's "Penitent Magdalene," in the collection of Florence's Museo dell'Opera del Duomo.

Bertoldo's 1478 medal commemorating the Pazzi conspiracy is among the Renaissance's most innovative, according to Noelle. On April 26, 1478, Francesco Pazzi murdered Giuliano de' Medici during Mass at Florence Cathedral, while the latter's brother Lorenzo escaped and managed to thwart the coup to overthrow the Medici. Bertoldo's medal innovatively features Giuliano's story on one side and Lorenzo's on the other; one can make out Giuliano's corpse in the bottom of one side, while Lorenzo's side shows him fleeing his pursuers through the choir.

The medal offers a large portrait of each brother above the scene, almost like each head is mounted above the choir. Where other medals have obviously primary and secondary sides, both sides of this medal are of equal weight. Lorenzo looks to the right, while Giuliano looks to left, and each side, according to Noelle, shows a portrait, an allegory, and a scene. Bertoldo flipped the octagonal choir in each side, bringing to a flat surface a sculpture's ability to render in the round, which hadn't previously been done. Giuliano's side reference Pallas Athena, his symbol, and Lorenzo's his emblem, a lion.

By having the brothers face each other on opposite sides of the medal, Bertoldo encouraged viewers to flip the medal. "Working together, it's a very striking piece of propaganda," Noelle says. And the more than 20 copies made at the time (including one sent to the French king) helped raise sympathy for Lorenzo, Bertoldo's patron, and his family. This work, the only portrait Lorenzo ever commissioned, was a rare exception to his desire to appear as a private citizen rather than a ruler. Viewers might also feel that it in some ways anticipates aspects of animation.

The jawline in Bertoldo's portrait of Giuliano is one reason why some scholars have questioned the identification of a circa-1475-1478 terracotta bust of Verrocchio's, which the National Gallery show displays as "convincingly" identifiable as Giuliano de' Medici. A ghastly face on the figure's armor breastplate might be Medusa (the snake-haired Gorgon of myth), Nemesis (a goddess popular among soldiers), or a Fury (goddess of vengeance). Among the arguments for this being Giuliano, per the catalog, are Giuliano's Medusa-adorned armor in a 1475 joust (during which he carried a banner of Verrocchio's design) and the bust's uplifted look, which echoes a poem commemorating the joust. The poem records Cupid telling Giuliano to look up at a vision of his beloved, Simonetta Vespucci, per the catalog.

Advertisement

A clear star of the show is the David, which used to contain the rock lodged into Goliath's head and was created for Medici patrons. (The brothers later sold it, perhaps at an intentionally-deep discount as a propagandist gift, to the city for installation in the town hall, Palazzo Vecchio.) The young shepherd and soon-to-be-king wears armor and holds a sword in his right hand, as his bent left arm rests on his waist.

Where prior artists tended to skimp on details of the giant's head, Verrocchio depicted teeth and eyelashes, the exhibition catalog notes. "Goliath's weary face unexpectedly invites compassion," it adds. That's an interpretive move that surfaces in Tom Gauld's 2011 graphic novel Goliath, but otherwise conjures no other immediate examples.

Florentines embraced the biblical David as a symbol of their own small stature in the face of more powerful foes in Rome and in Milan, evidenced by the Davids, which Donatello (circa 1440) and Michelangelo (1501-1504) sculpted. But Verrocchio's David (circa 1465) is more than just an underdog. The complicated, sly expression foreshadows David's meteoric rise to king, when he was both "sweet singer of Israel" (2 Samuel 23:1) and someone whose hands were too stained with blood (1 Chronicles 28:1) to construct the temple. That task fell instead to his son Solomon.

Detail of "St. Jerome," circa 1465-1466, probably by Donatello and Bertoldo di Giovanni, in wood, gesso and paint at the Pinacoteca Comunale in Faenza, Italy (Menachem Wecker)

The National Gallery exhibit also includes a circa-1465 painting of St. Jerome, variously attributed to other artists in the past but given to Verrocchio some 30 years ago. The saint (depicted from head to mid-chest) lacks the gory drama of Bertoldo's sculpture, but is identifiable as Jerome for its bare chest and shoulders, typical of an ascetic. This painting on paper, glued to a panel, portrays a face that is pure poetry in its upturned gaze, wrinkled skin, and enchanting symphony of whites along the chin and neck, hairline, eyebrows and cheeks.

The picture portrays a saint rather than a member of the Medici family, but this man whose appearance draws the viewer in without being, strictly speaking, handsome, might as well have an emblematic Medici nose. About a polychrome terracotta sculpture of Lorenzo, the exhibit notes say the Medici subject was described in a 1494 biography as having a "face that showed great dignity but no beauty." The same could be said of this St. Jerome, which further illustrates how for Verrocchio, Bertoldo and countless others in Renaissance Italy, the boundary between Medici and biblical saint was often rather intentionally obscured.

[Menachem Wecker is a freelance reporter in Washington, D.C.]