The tension between individual freedom and community responsibility may be hitting its tipping point — with community tilting into the winner’s column.

This contrast has always existed in American society but the Great Recession has put it into sharp focus: How do we respond to tough times? Are we individual actors who find our way alone, or do we pull together?

In the past, big social and economic issues were tackled by big social and economic answers: the birth of unions, the creation of social security and the spread of the civil rights movement. But the fire this time has generated no long-lasting social response. Occupy Wall Street came and went, and has not yet served as the spark that lit something larger.

Most stories of this recession seem to concentrate on individuals, people in your hometown who got handed lemons and made lemonade: He was laid off at a factory but now runs an at-your-home car wash service; she was unemployed for a year until she started a daycare center in her house, etc.

None of those stories has provided an answer to our issues — and it feels like we as a society are starting to notice. The unique tales of survival are fine as far as they go, but they don’t go nearly far enough. What should we do now? Is it time for us to once again pull together and tackle problems in a cohesive way?

According to a flood of recent writings, it just may be.

A recent Time magazine cover story by Joel Stein looks at what is dubbed “The Me Me Me Generation,” the children of baby boomers also sometimes called “Millenials.” Stein’s story ends on a positive note about this generation, but spends most of its time noting these people are pretty much on their own, coming of age in a society with no clear authority figures nor sets of rules with broad consensus.

Partly, Stein writes, we begat all this in the 1970s, when we started raising Millennials and immersed them in the self-esteem movement. The ethos of everyone-is-special, everyone-gets-a-medal doesn’t encourage cohesion, group action and big ideas.

The focus on the self rather than the other doesn’t breed a wide worldview. High school English teacher David McCullough became famous last year for his speech to graduates titled “You Are Not Special.” He told his students: “Climb the mountain so you can see the world, not so the world can see you.”

Author George Packer addresses this same shift in his latest book, “The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America.” He reports on individuals battling both the Great Recession and longer-term social and economic trends, and weaves through it his sense that a sense of community and social fabric has been unwinding in America for some time.

In an NPR interview, Packer said there was an unspoken contract in the country that ran from about the 1930s through the 1970s: People traded some constraints on personal freedom for security and forward social movement, a goal of making sure the next generation would do better than the last.

But now, he says, “many Americans feel they are all alone.” We have all the freedom we want, but are left in the darkness to enjoy it.

A similar theme emerges from Ross Douthat’s Sunday New York Times column, titled “All the Lonely People.” He examines a disturbing American trend in the sharp rise of suicides. All other forms of crime have dropped markedly, but suicides are on the increase — up 30 percent in the millennium’s first decade for people ages 35 to 54.

Douthat cites studies that show the strong link between suicide and weak social ties. A University of Virginia sociologist quoted in the column pointed out that people, especially men, are more likely to take their lives in hard times when they feel “disconnected from society’s core institutions” like marriage and religious community.

Virtual connections like Facebook and Twitter provide something of a balm, but Douthat says it is the traditional forms of community that work best: a steady job with a group of stable co-workers; church; volunteer groups. But, he writes, that is tougher than ever in a society that trumpets the individual, the everyone-is-special ethos:

“The problem is that as it’s grown easier to be remarkable and unusual, it’s arguably grown harder to be ordinary. To be the kind of person who doesn’t want to write his own life script, or invent her own idiosyncratic career path. To enjoy the stability and comfort of inherited obligations and expectations, rather than constantly having to strike out on your own,” Douthat wrote.

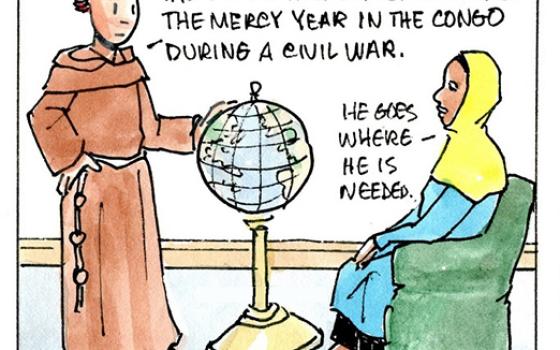

The Catholic social justice ethic, to me, has always worked to find a balance. Catholicism recognizes the value of the individual, the dignity of the person, while understanding that people find so many things (solace, inspiration, action) in the ties of community and congregation.

For decades, the American focus has been on the individual to the near exclusion of all other values. This has created a more tolerant society, and one that is in many ways more vibrant and entrepreneurial. But it has also sparked an atomization, a shredded social fabric, a self-centered loneliness that is just now being fully understood.

The discussion seems to be tipping back toward the center, toward the place where answers come from both exceptional individuals and tight-knit communities, toward the place where no one feels alone in a world filled with the unforeseen.