Australian Catholic University theologian Sr. Maeve Heaney, Verbum Dei, with a copy of her book Suspended God: Music and a Theology of Doubt (Courtesy of Australian Catholic University)

Christian theology has long been based on words. But are there other ways of understanding faith? Can music be one of them? If so, can music help Christians affirm their faith in new ways?

Irish theologian Sr. Maeve Heaney, a member of the Verbum Dei Community who teaches at Australian Catholic University in Brisbane, explores these questions in her new book, Suspended God: Music and a Theology of Doubt.

The book is a kind of genre-breaker: Questions of faith, often framed as questions of doubt, are posed through the lens of Christian thinkers, from Carmelite St. Teresa of Ávila (1515-82) to modern figures such as the Swiss reformed theologian Karl Barth (1886-1968) and the Jesuit theologian Fr. Karl Rahner (1904-84).

A key figure in the book is Fr. Bernard Lonergan (1904-1984), a Canadian Jesuit who broke new ground in his analysis of the cultural changes affecting the church and how theology might need to change to address them.

The church, Lonergan famously quipped, always seems to arrive at the issues it faces "a little late and out of breath," unprepared for the task at hand. To address this, theological method needs a radical transformation, he argued.

Heaney takes on Lonergan's challenge by seeking to bring the arts fully into theological methodology.

Her reflection on each of the profiled figures includes a song from an album that accompanies the book, "Strange Life: The Music of Doubtful Faith."

In weaving together word and music, thought and feeling, Heaney said her work seeks to help readers and listeners make sense of life — because making sense of life is not only done with words.

"Suspended God: Music and a Theology of Doubt is built on the conviction," Heaney said in an ACU release about the book, "that good theology is born of convinced believers who are willing to take their questions, and their doubts, seriously."

______

GSR: The book seems to have two threads: One is supporting doubt as a way to open up religious faith and theological reflection — the title "Suspended God" seems to suggest that. The other is to use music to open up horizons in that wider space where doubt has a role. Is that a correct way to read the book? How would you describe / characterize the book for those interested in reading it?

Heaney: "Doubt" is an interesting word, and I was quite conscious when I was using it, but I also unpack quite clearly what I mean by doubt. I'm not talking about the radical existential doubt that has us always in anxiety, although I think sometimes that can hit us and it can provoke interesting things. So, I don't think we should be scared of it.

What I'm talking about is doubt in that broad sense of when we question, when we don't understand, because we can hold a deep certitude, and here I think it's John Henry Newman who differentiates between certainty and certitude. I can hold a deep certitude that God is good, that the church is my space of belonging, and that Christ is real, and yet have lots of uncertainty about certain questions about different areas of either praxis or life or even doctrine in terms of how we understand it.

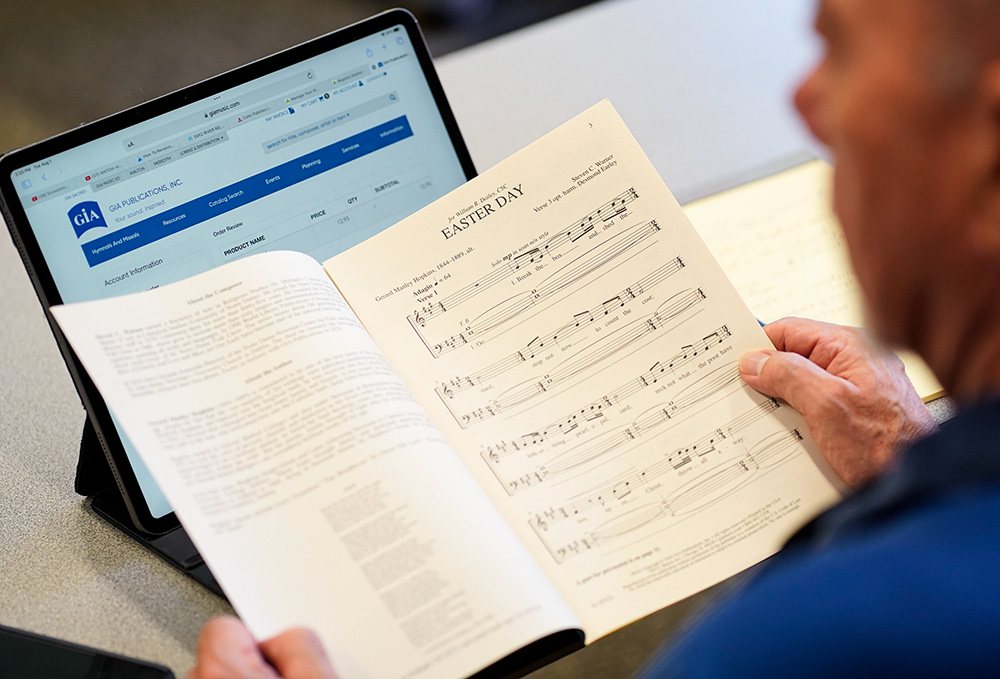

A participant looks at a booklet while attending a workshop on Irish sacred music during the Liturgical Music Institute at Immaculate Conception Seminary in Huntington, New York, Aug. 1, 2023. (OSV News/Gregory A. Shemitz)

What I'm trying to say is questions pull us forward, and when we doubt things, when we put things in question, it can be a really helpful space for us to grow and to know more, because when we think we know it all, actually we don't journey. And let's face it, we are lifelong learners.

So yes, doubt, but doubt is understood as the humility implicit in knowing that we do not know everything and that while revelation in Christ is complete, our understanding of the same is not.

And, of course, there is the underlying theme of music.

Yes, absolutely music. And what I'm trying to say with music is that music opens a different kind of space. It's not me trying to tell you something and you get the right message. It's me, or other musicians, opening a space to share an experience or communicate something, but you can interpret it differently. That's art.

Music educators from Catholic schools around the Galveston-Houston Archdiocese rehearse music before Mass Oct. 10, 2022, at the Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in Houston. (CNS/Texas Catholic Herald/James Ramos)

Specifically, music helps us open spaces deeper than our controlled convictions or certainties. So, I think the two can come together.

I'm not saying all music, all the time, anywhere. But I am saying it's a symbolic form, a way that we make sense of things that helps us access that part of us that questions, and that grows and that needs to grow as adults in the faith.

At one point, you ask, "What use are the arts?" Can we expand on that and ask what use are the arts in religious practice and the doing of theology?

Culture often sidelines the arts, but so does theology. Now, I would caveat that there are really creative spaces in theology emerging now, and I think theology and the arts both can be prophetic and are being prophetic. So, people are coming in sideways and saying, "No, we need to stretch things." That's part of what I'm trying to do.

Marble seated harp figure, Cycladic culture, 2800–2700 B.C. (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

But the problem is, and here I come directly to your question, what use are the arts in religious practice and the doing of theology? Human beings were artistic before they were philosophers and before they were discursive. They were already painting, they were already drumming, they were already making music.

So, if we sacrifice and sideline what is an essential aspect of human life, how can we honor Christianity's vision of the human person?

And if the arts are a space in which we symbolize what actually is important to us, whether that's within the church or outside the church, if we sideline the arts, how are we ever going to communicate with the world that we are not listening to?

As long as we keep it on the shelf or in the back room, we're not using all the gifts that God has given us to be able to mediate faith and translate faith for culture and for the church, which is one of the essential roles of theology.

The arts need to regain their primary role with all the complexity that that implies. The arts can be unruly, but to be honest, so can philosophers and theologians.

Music has been important to many theologians, including the late Pope Benedict XVI. He played the piano and loved music. On some level, he was able to merge the worlds of music and words.

That's absolutely right. And Karl Barth, the same. He loved Mozart. Music was part of the initial start of his day. Before he did any writing, he listened to music.

Advertisement

How would you respond to those who might doubt your approach — about merging thought and music? How would you respond to people who say, "We just can't accept this"?

I understand that, for some people, for whom words seem to be the central axis for theology, and perhaps the only one, and this includes very fine friends and theologians who would struggle a bit with what I'm suggesting, I understand that they're trying to maintain the quality of theological thought, and I honor that.

I'm not saying, "You words, me music." I dislike shabby theology because shabby theology and shabby thought are harmful to the church. It can easily become ideological. It's harmful. So we need to think well, and words guarantee that. Nothing in me wants to defend feeling over reason. Let me put it like that.

But I'd also like to challenge the separation. For example, when we say of our nonverbal reactions, "They're only feelings," is this correct? I have to unpack that a bit. When someone tells you a blatant lie, does your head hurt or do your feelings hurt, or both?

Our understanding, our comprehension of reality, is our whole embodied self, made of mind, feelings and imagination.

Angels play music in medieval stained glass at the Musée de Cluny in Paris. (Wikimedia Commons/Allie_Caulfield)

So, I'm not saying feeling against thought. I am saying symbol is bigger, and I'm asking us to be honest about the history of symbol and thought, which have not always been as separate as they are now.

This is the argument of the first part of the book, wherein two chapters, I trace the history of music in theology and the history of theology in music. That history is real and vibrant. So, I'm actually challenging our short memory in understanding that it has ever been thus. Our greatest philosophers and theologians were also musicians, and they interchanged some of the philosophies on which we built our thought.

We also need to recognize that the world in which we live is changing. Words don't signify the way they did. As theologians, either we "up our game" in understanding how the next generation actually symbolizes and understands their faith, and attempt to dialogue with them there, or we will live in an ever-smaller corner of the world, and faith will disperse.

So, the concern of this book is about faith translation as well, and how we need to dialogue with music and culture.

A mariachi band plays music during a Spanish-language Mass marking the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe at Resurrection Church in Farmingville, New York, Dec. 12, 2021. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

That raises a good point: Maybe there's now more space for what you advocate. Do you feel that there is more space for what you're saying than there would have been, let's say, 20, 30, 40 years ago? Added to that — there are more women doing theology, including more sisters.

I think you're right. It's slow, but I think there definitely is a shift taking place. And I think it comes from various things.

There's an awareness that culture is shifting. Without wanting to essentialize how men and women think, I do think that as a broad category, women are more connected about things, and the life experiences we bring into theology invite us to think differently.

But I'd also like to add that because theology's center is moving from Western to being more diverse in culture, that also brings a different sensibility. African cultures, for example, bring an awareness of music and embodiment. The liberation theologies, more broadly, minority theologies, are challenging a kind of structured way in which everything is done "like this."

It's also a style of thinking. So bringing in diverse voices challenges that style, and often that's done very creatively. So yes, I think things are shifting, and I think for the better, and I don't want one to substitute the other. I just want us to listen to all voices, if that makes sense.

A group of local drummers and dancers from Vitting village in Tamale, Ghana (Wikimedia Commons/Shahadusadik)

We're being invited to be aware of the different levels of our sense of things. So, our psyche isn't just theory or organization, it's also relationality, connectivity, imagination, culture, interaction, men and women, different cultures. All of that is messy, but it's rich.

In the book, you say theology has sidelined beauty in its work, the supreme beauty found in Christ. Does that mean that beauty not only encompasses music but other types of art? And must art always be "beautiful" to make such claims? Surely, there are examples of art and music that aren't beautiful, especially in modern times. Is there such a thing as complicated beauty?

This is such an important question. We need to hold together two things in this space. Augustine was great on this, and Pierangelo Sequeri, an Italian theologian who is one of the figures in the book, is also brilliant on this theme. We need to hold together God as beautiful and God as crucified, and there is nothing beautiful about the crucifixion, and yet it is the quintessential symbol of our faith in which we find beauty. I mean, I'm moved by crucifixes in moments of joy and moments of deep pain.

Life is painful. We live in a broken world, we live in an ugly world in many ways, and yet we believe that God is beautiful, but it's this God that's beautiful, it's the God who has loved us to the extreme, it's the God who became human in the messiness, it's the God who was crucified, killed, suffered, died, was tired, frustrated. It's that God that we're calling beauty.

We know what beauty is in the face of Christ if we're talking as Christians. It's not aesthetic beauty that hasn't gone through pain. It's the beauty of the face of a mother who has loved and has lines in her lines because there's been so much love there, and yet love can flow through. That's beautiful.

Women dance on stage during Lunar New Year festivities at St. Michael Church in Flushing, New York, Feb. 11. (OSV News/Gregory A. Shemitz)

You use music as a verb as well as a noun, as in everyone "musics." That's a really interesting idea. What do you mean by the term "musics" or "musicking"?

Well, music and "musicking" as a verb is an expression created and coined by Christopher Small, a New Zealand musicologist. I think it's brilliant. And the main reason I use it is that it shows the dynamic nature of music because music isn't some "thing," it's not the sheet of music that you get. Music is what happens when music is made. And everyone, in some way, "musics"!

It's in time, and it's in life. It's about finding where music is and naming it broadly so that we're all in this conversation about the importance of music in theology and life, indeed — in fact, the very life of the church itself.

We don't know much about the music of Jesus' time. But Jesus would've been a very strange Jew if he hadn't sung the songs in his time. There was a culture of singing then. It is unlikely that Christ didn't sing.

So, music as intrinsic to life is our starting point, and how music, life and Christian faith aid us in the task of understanding our faith, as St. Anselm said, and bridging between that faith and the culture we live in, as Lonergan said.

This is what theology is called to do, for those of us who are theologians, but also for every Christian, called to "give reason for the hope that sustains us."